Parents dream of a cure for a childhood dementia that comes with a ‘death sentence’

Like Alzheimer’s disease in older adults, Sanfilippo syndrome affects the cognitive ability of the very young.

- Share via

As parents watch their kids transition from infancy into childhood, it’s common to look for signs of progressing development. Are they sleeping through the night? Can they remember new words and use them in a sentence? Have they continued to develop new motor skills?

But for a small group of parents whose children have a type of childhood dementia called Sanfilippo syndrome, those telltale signs may be delayed or never come.

With an older daughter at home, Covina resident Muna Hattar-Mendoza and her husband, Henry Mendoza, knew what signs to look for to gauge whether their younger daughter’s development was on track. But Rose Mendoza, 9, wasn’t meeting the same developmental milestones that her older sister, Cecilia Mendoza, 11, had achieved by the same age.

Rose had difficulty breathing and pneumonia as a newborn, but by the time she reached 8 months, she seemed to be doing much better, Hattar-Mendoza said. Then, at 18 months, she wasn’t speaking as much as she should be, and by 2, she couldn’t say two-word sentences, a skill the Mayo Clinic reports is typically achieved at that age.

Rose started working with speech, occupational and physical therapists to build her language and motor skills. Specialists thought her chronic ear infections might be delaying her ability to speak.

When putting tubes in Rose’s ears didn’t help, Hattar-Mendoza said she knew they needed to pursue further diagnosis.

“At that point, my internal cues as a mom [were] like, this is serious and this is significant,” she said.

After being tested by a geneticist, Rose was diagnosed with Sanfilippo syndrome, a rare, genetic disease that disrupts the body’s ability to break down and use carbohydrates.

According to the Cure Sanfilippo Foundation, an estimated 1 in every 70,000 children are born with the disease. Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego reports that, although symptoms don’t typically appear at birth, they often develop between ages 2 and 6.

The symptoms, which get progressively worse over time, include delayed speech, seizures, difficulty with communication and social skills, movement disorders and intellectual disability. Over time, a child may also experience hearing loss, arthritis, visual impairment, chronic diarrhea, frequent respiratory infections and enlargement of the liver and spleen.

Osmosis — an online platform focused on medical education — reports that diagnosis of the condition is obtained through a physical exam, looking at the medical and family history, genetic testing, measurement of enzyme activity and urine tests. In the latter, the exam looks for elevated levels of heparan sulfate, a complex carbohydrate that accumulates in the body of those with Sanfilippo syndrome.

There are no medications or treatments approved to cure or reverse the progress of the disease. Depending on the type of Sanfilippo syndrome the child has, their life expectancy can range from 10 to 20 years, according to Sanfilippo News.

Because it is such a rare condition and because many children with Sanfilippo are also on the autism spectrum, the disease isn’t always properly diagnosed, said Dr. Cara O’Neill, a pediatrician and Cure Sanfilippo Foundation‘s chief science officer.

It’s an experience that O’Neill and her husband, Glenn, in South Carolina, know from personal experience with their daughter Eliza. Following her autism diagnosis, Eliza started physical, speech and occupational therapy sessions every week, but O’Neill said she continued to fall behind her peers.

Her parents pursued additional testing, including an MRI, which showed that Eliza’s brain had some characteristic signs of the disease. It was later confirmed by a urine test showing increased levels of heparan sulfate.

After Eliza’s Sanfilippo diagnosis, the O’Neills started the Cure Sanfilippo Foundation to raise awareness of the disease and funds to support research.

Their efforts include a push for genetic testing of children who display birth defects before they turn 1, and for anyone who has a developmental or intellectual disability before they turn 18.

“It’s understandably difficult for physicians to know every 7,000 of the rare diseases that are out there,” O’Neill said. “We just need a better safety net of catching these kids early that doesn’t require getting lucky and somebody happening to think about a particular rare disease.”

Through genetic tests, children can be diagnosed with Sanfilippo syndrome earlier. Although there is not yet a cure for the disease, there are ongoing studies searching for treatments.

Having a diagnosis meant that Los Angeles resident Jen Sarkar’s son could participate in a clinical trial testing the effects of rheumatoid arthritis medication on children with Sanfilippo syndrome.

Although the development of symptoms in many babies and toddlers with Sanfilippo syndrome often mirror one another, Sarkar said her 10-year-old son’s experience was very different.

As a baby, Carter Sarkar was a happy and healthy jokester developing skills ahead of the curve. At 18 months, he was able to put together simple two-word sentences such as “Mom, milk.”

After transitioning into day care, Sarkar said her son’s health started to change drastically. Carter started having recurring sinus and ear infections, followed by chronic pancreatitis that landed him in the hospital for about two weeks just before his second birthday.

A few months later, she said her formerly happy baby starting displaying symptoms of depression, and he was only using about 10 words. But the doctor kept saying Carter’s behavior was normal, given his health issues.

“I was told by her that it was completely normal, don’t worry about it,” Sarkar said. “He’s a medically complex kid, so sometimes regression happens when he’s in and out of the hospital.”

In the summer of 2015, a gastrointestinal specialist suggested they work with a geneticist to find a diagnosis, as Carter still wasn’t potty trained and hadn’t made major improvements despite intensive speech and physical therapy.

Within 30 seconds of walking into the geneticist’s office, he told Sarkar that he suspected Carter had Sanfilippo syndrome. Two inconclusive urine tests and a round of blood tests later, they learned that the geneticist’s suspicions were true during a phone call on the last day of their Disney World vacation.

“It was a really hard situation — I think my husband and I maybe said two words to each other on the flight home,” Sarkar said. “What do you do? Your kid just got a death sentence.”

Sarkar said her son’s quality of life has improved significantly since he first started participating in the clinical trial, which involved twice-daily shots of a rheumatoid arthritis medication called Anakinra.

The Phase 2/3 trial involving 20 participants was just completed in March, so the families are still awaiting the final results, but Sarkar said she knows it made a difference for her son. The day Carter came home after his first dose of medication, he rode his scooter for the first time in three months.

After continuing with the injections, he was able to recall songs, use words his parents thought he had lost and speak in full sentences. Carter was also able to sleep through the night and to take fewer painkillers unless he was having a pancreatic attack.

“It might have been spontaneous, but it was a difference for him,” she said. “Overall, the key points are that he was happier, he was in less pain, and that’s a huge thing.”

Today, Carter is still able to walk freely, eat without swallowing issues, engage with his family members, sustain eye contact and use a handful of words, which Sarkar said is a blessing, considering how many of his Sanfilippo “siblings” fare at his age.

“It seems like it’s so slow, but it happens so fast,” Sarkar said of his regression. “It is really hard as a parent to watch your kid as you’re just getting to know him and his personality is coming through, and it’s being taken away from you at the same time.”

Through all the ups and downs, Hattar-Mendoza said it is key to build a good relationship with the pediatrician and connect with other families of children living with Sanfilippo syndrome.

Hattar-Mendoza said getting connected with the Sanfilippo community led to her daughter Rose participating in a gene therapy clinical trial when she was 4. After the one-time intervention, she was gradually able to learn more words, dress herself and communicate with her family.

“In my view, it did wonders for her,” Hattar-Mendoza said.

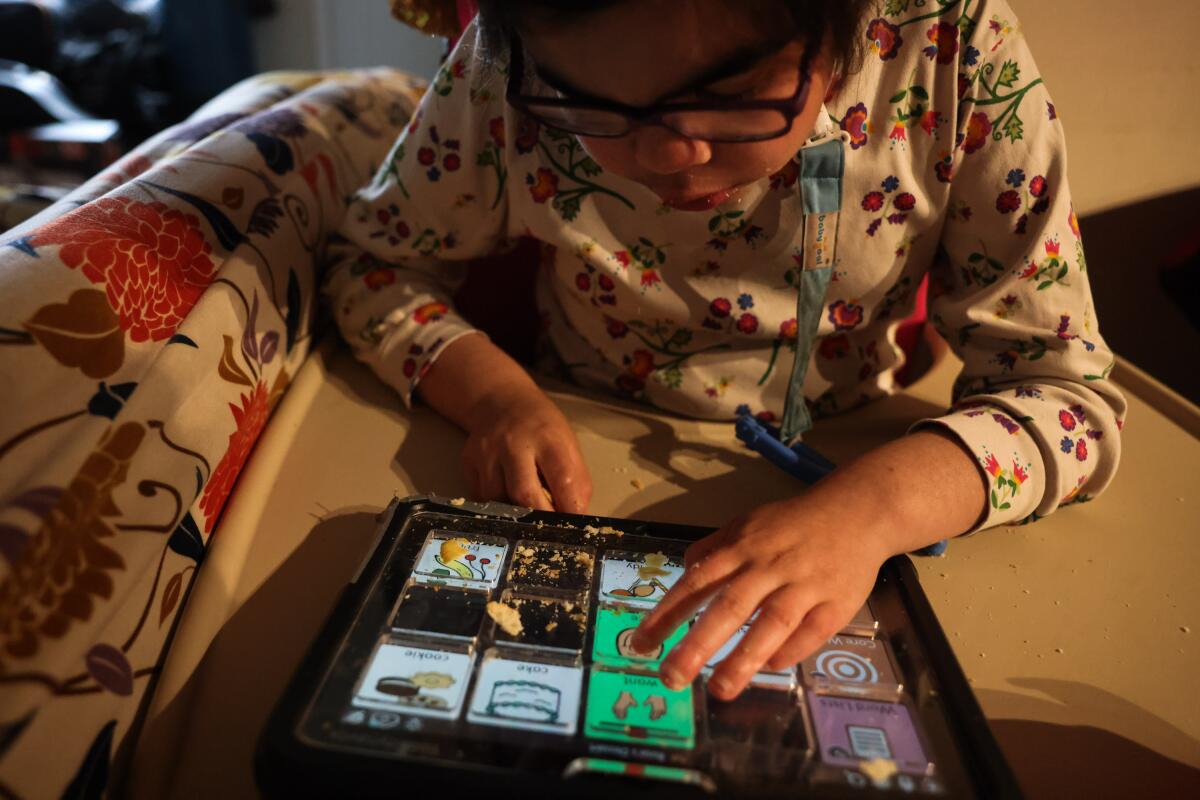

Last fall, Rose started to relearn skills they thought she had forgotten, including using utensils and having conversations through her iPad’s communication program, which she often uses to cue her favorite word: cookie.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.