Jean Koch, a fixture on The Times’ letters page for 55 years, dies at 100

- Share via

About eight months before Los Angeles activist, writer and matriarch Jean Koch’s death on April 11, she went to church and took a seat in the courtyard. Someone poured her a glass of pinot grigio. Someone else set up a microphone.

It was her 100th birthday party. Koch, sporting a dash of bright blue in her silver hair, greeted friends, laughed often and listened as closely as her imperfect hearing would allow as her five children took turns telling stories.

How many times had Jean been arrested? Perhaps only once, in the 1980s, when daughter Jill Tovey and her husband had to bail her out after a protest over Nicaragua. But there were so many marches and protests.

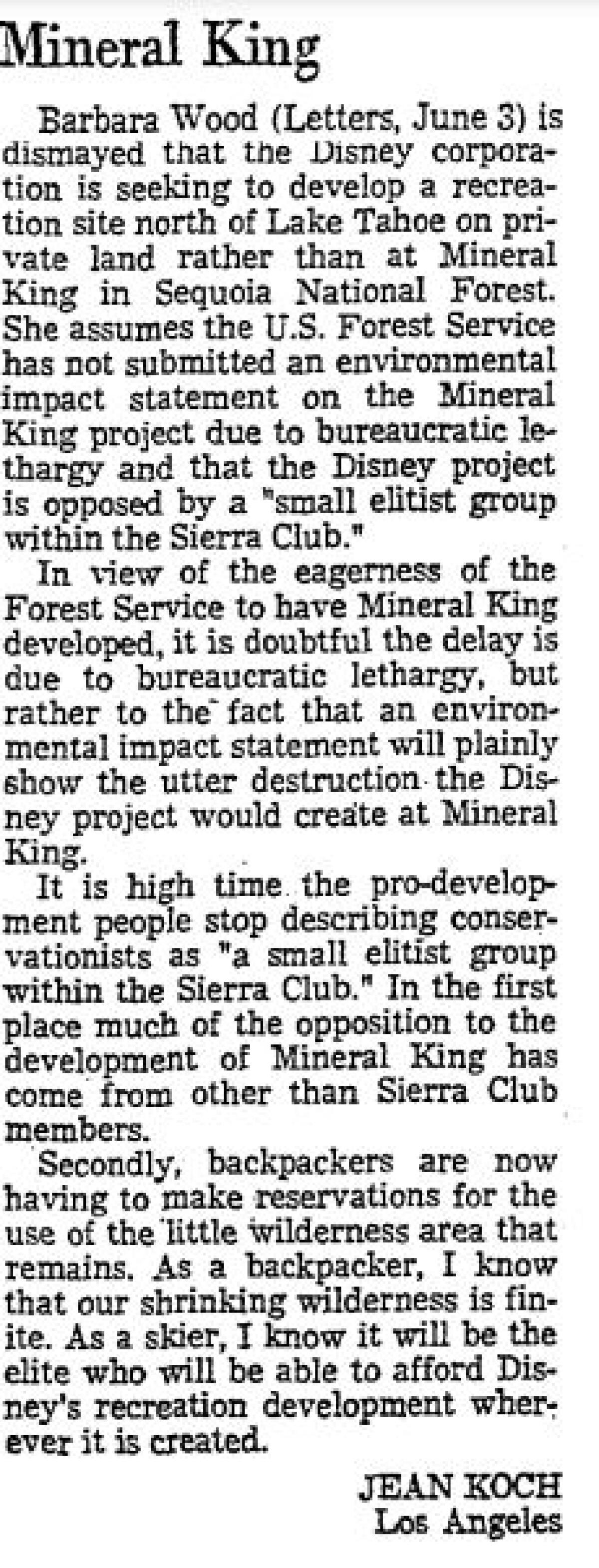

And how many letters to the editor had Koch published? At least 65 in the Los Angeles Times over 55 years, which puts her among the opinion page’s most frequent contributors through the decades.

Koch weighed in on sustainable energy, street vendors, water conservation, the death penalty, abortion, civil rights and Latin America. But she also wrote about less momentous subjects, like the part-time job at Sears that got her husband through medical school; how to banish rats from City Hall (get a cat); and how her family spent the night after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake (in an orange grove, fearful of aftershocks).

“When I tell my friends I have a solar clothes dryer, they are amazed that I have such a fantastic appliance,” she wrote on April 18, 2009, “until I add that it is a line between two poles.”

Koch was not quite 5 feet tall, with energy and a sense of engagement that defied actuarial tables. Until age 98, Koch volunteered weekly at a food bank, picking up and distributing groceries to neighbors in need. Until 99, she drove herself to the 99-cent store and church, when the pandemic permitted.

At 96, serving on a pastoral search committee for her church, Koch wanted to be sure that a promising candidate was made of strong enough stuff.

“She was little but fierce,” recalled the Rev. Ashley Hiestand of Mt. Hollywood United Church of Christ. “And she fired out a question about whether I’d be willing to be involved in protests … She walked her faith.”

“She was a rebel,” Tovey said.

“Fiery,” said daughter Christine Koch.

She had grown up in a conservative family on an orange and walnut farm in Garden Grove, forbidden from dancing. Yet after voting for Richard Nixon in 1960 and Barry Goldwater in 1964, she evolved into a Democrat, urban environmentalist and civil-rights crusader.

Kathryn Jean Holt was about 20, playing the marimba at an Orange County USO dance, when she met Richard Koch, an Air Force bombardier and soon-to-be medical student. After they married in late 1943, he was dispatched to Europe, where he was shot down and taken prisoner on Easter Sunday, 1944.

For 13 of their first 19 months as a married couple, Richard Koch was locked in a German prison camp. By the time he was released in May 1945, Jean Koch was on her way to a degree in elementary education at San Jose State.

The couple moved a few times as Richard Koch finished his training as a doctor and began work as a pediatrician, but in the mid-1950s, they found their way back to Los Angeles County. Jean Koch took the lead in raising five children while Richard Koch worked at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

For years, Tovey recalled, “my mom and dad were always canceling out each other’s votes. Then somewhere along the line, I don’t know exactly when that happened, but all of a sudden she was a Democrat.”

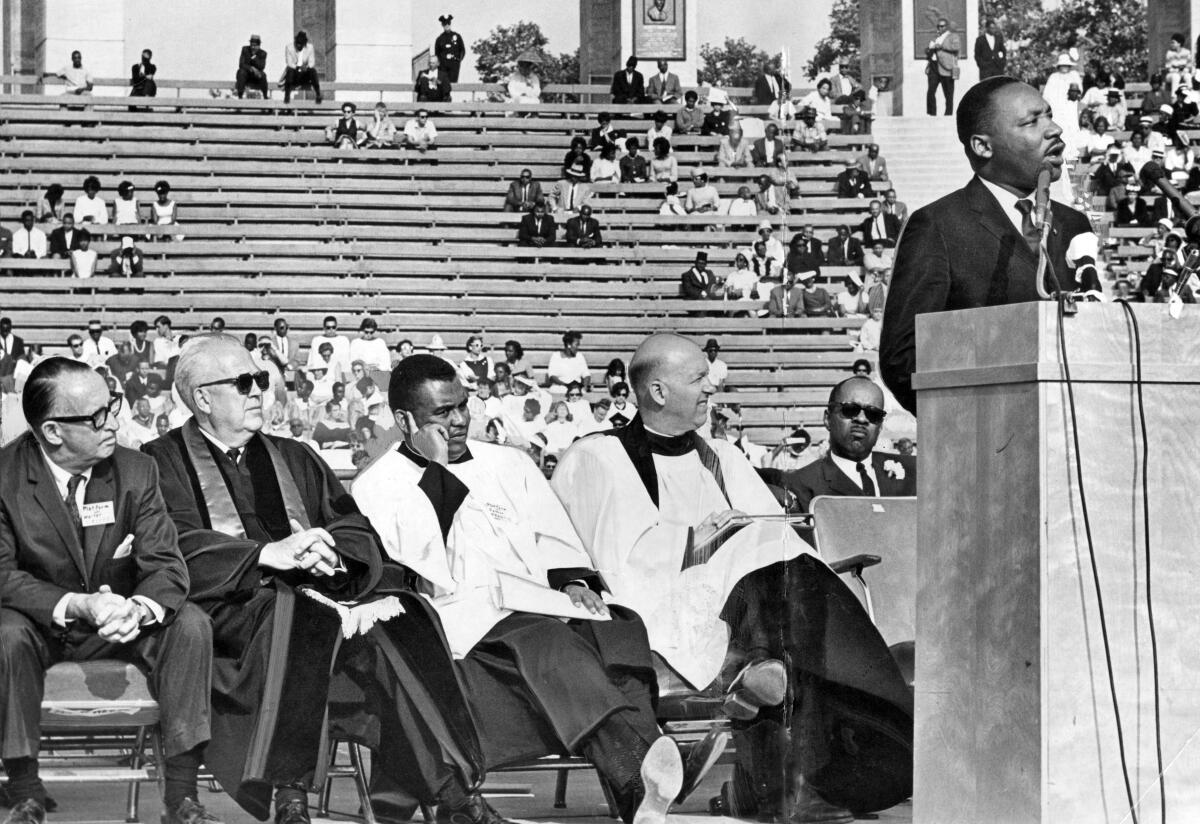

Daughter Leslie Ochs’ theory: “I think it was Martin Luther King. I think that swept her up and she chose sides.”

“It was an evolution,” daughter Christine Koch said. “She was very touched by Martin Luther King and she sang in the choir at the L.A. Coliseum when he spoke” in 1964.

Around this time, the letters to The Times began.

On Feb. 26, 1968, Koch wrote to denounce the death penalty: “There is no logical reason for continuing this barbaric practice. It cannot be said to be a deterrent to crime since statistics show us that states and countries where capital punishment has been abolished have the same, if not a lower, murder rate than they did when they practiced it.”

On Dec. 14, 1971, in response to a column about shortages of open space in the city, she wrote: “Why not multi-purpose cemeteries that would double as golf courses, picnic areas or playgrounds?”

The Koch family lived many years in Westchester, where Jean Koch volunteered for a fair-housing organization, posing as a would-be tenant and teaming with Black allies to see if prospective landlords would treat them equally. In 1970, when the family left for a sabbatical year in Trujillo, Peru, the Kochs made sure to rent their home to a Black family, apparently the first in the neighborhood.

Eventually the Kochs settled in Los Feliz, near Children’s Hospital, heading every summer to a mountain cabin in Mineral King, now part of Sequoia National Park. Koch joined the Mt. Hollywood church, rose to leadership, sang in the choir, played marimba occasionally, performed in community theater and kept writing letters.

March 8, 1976: “When we consider that the nuclear industry is piling up tons of deadly waste materials annually, for which there is no proven safe storage method, and much of which will remain deadly for 500,000 years, it is obvious that we must change our ways. And when we consider the dwindling supply of fossil fuel on this planet, the same realization is obvious.”

Sept. 25, 1978: “I am happy for my grandson, who rides the bus to a school where he is making new friends of all colors. Hopefully, when he becomes an adult, busing to achieve integration won’t be necessary.”

May 13, 1988: “Cut down on toilet flushing. One flush will do for the whole family at bedtime. Remember, each flush uses 8 gallons of water.”

)

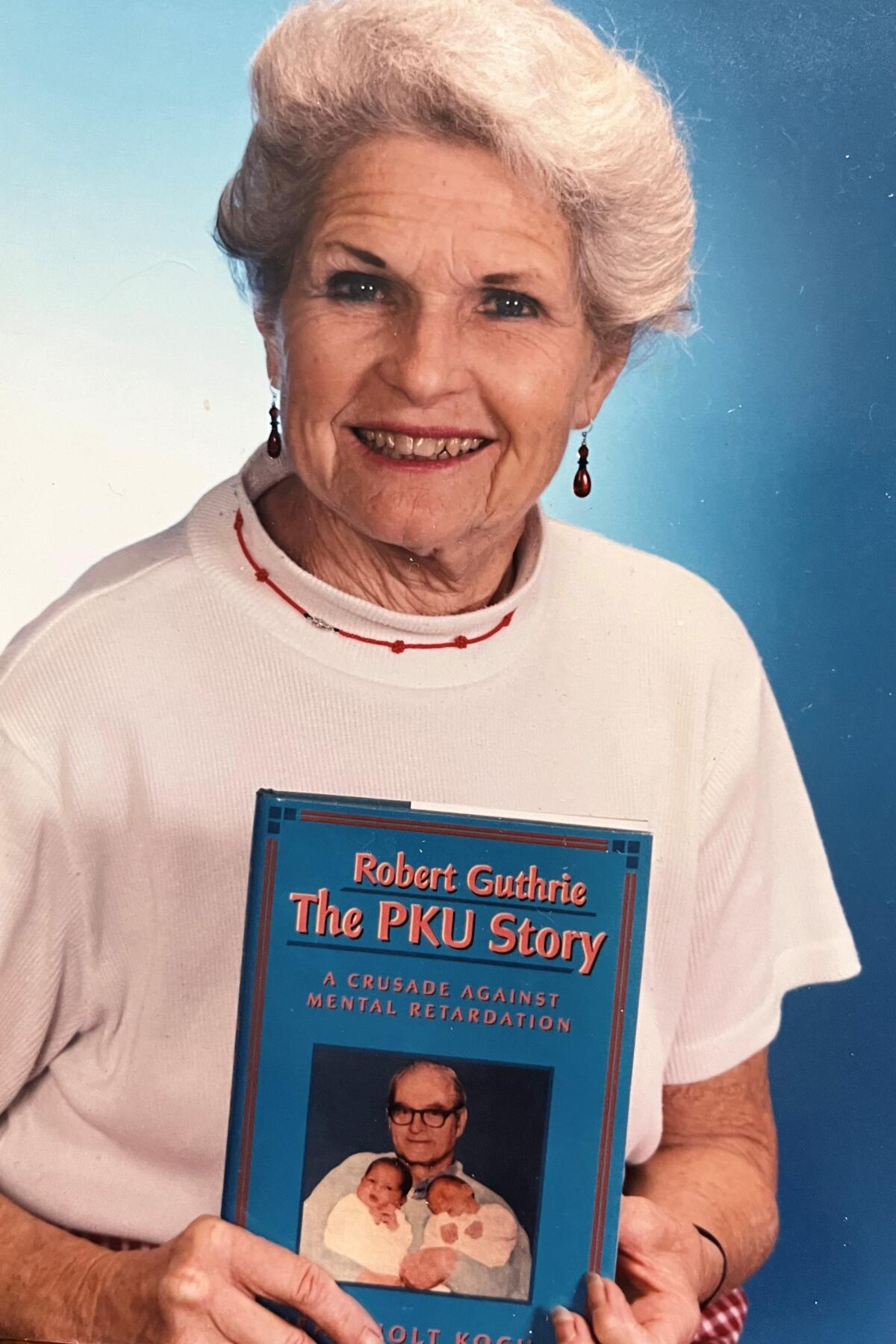

At Children’s Hospital, Richard Koch devoted most of his career to developmental disabilities, especially the early detection and prevention of phenylketonuria, commonly called PKU. In 1974, using the preferred language of the era, Richard and Jean Koch cowrote the book “Understanding the Mentally Retarded Child: A New Approach,” published by Random House.

In 1997, Jean Koch published “Robert Guthrie – the PKU Story,” a biography of the doctor who developed the first PKU screening test. In 2011, Richard Koch died. Jean Koch’s correspondence continued.

“She loved writing letters to the editor,” Tovey said. “One time she told me, ‘I’ve got to be careful [and not write too often].’ Because they keep track.’ ”

On Sept. 6, 2014, when The Times asked for verse from readers, Koch weighed in with a long poem about grammar, which included this couplet:

Put prepositions where they belong/

Not at the end. That is all wrong.

On Jan. 15, 2020, she recalled the temporary Quonset-hut city built for returning veterans in Griffith Park after World War II. “Somehow the city found it in its heart to offer a helping hand to people who were in need. It is unconscionable that we have people dying on our sidewalks because there is no shelter.”

Koch made it safely through the worst of the pandemic. But by March, non-COVID respiratory issues had put her in the hospital. By early April, nine days before her death, Koch was home in bed under hospice care.

That day a group from her church gathered around to sing some of her favorite hymns and showtunes. “She was singing with us,” Leslie Ochs said. “She was so grateful for that.”

In addition to Tovey and Ochs, Koch is by son Tom Koch, daughter Christine Koch, son Martin Koch, 10 grandchildren, 11 great-grandchildren and one great-great-granddaughter.

Los Angeles Times editorial library director Cary Schneider contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.