Tom Girardi gave $1 million in payments, gifts to top State Bar investigator, corruption probe finds

- Share via

Disbarred Los Angeles lawyer Tom Girardi funneled more than $1 million in gifts and payments to an investigator at the State Bar of California and the investigator’s wife, a USC accounting professor, according to a report released Friday.

The long-anticipated report, the result of a year-and-a-half investigation by a law firm working for the State Bar’s governing board, detailed how Girardi cultivated and sustained an “extensive network of connections at all levels” of the agency tasked with regulating California’s legal profession and described corruption beyond what is publicly known.

The investigator, Tom Layton, and his wife, Rose, received more than $600,000 in payments from Girardi, and Layton enjoyed the use of a credit card paid for by Girardi’s law firm, among other perks, according to the report.

The law firm’s investigation also documented how numerous State Bar officials with close ties to Girardi killed complaints that came into the agency or improperly closed cases about the lawyer’s alleged misconduct.

At least eight complaints were quashed by State Bar employees whose ties to the wealthy attorney tainted their decision to close the cases without any public discipline, according to the report by the law firm Halpern May Ybarra Gelberg LLP. In addition, two agency prosecutors who advocated taking action against Girardi’s law license were fired under questionable circumstances by top executives close to the lawyer, according to the report.

“The magnitude and duration of the transgressions reveal persistent institutional failure and a shocking past culture of unethical and unacceptable behavior,” said Ruben Duran, chair of the State Bar’s board of trustees, in a statement.

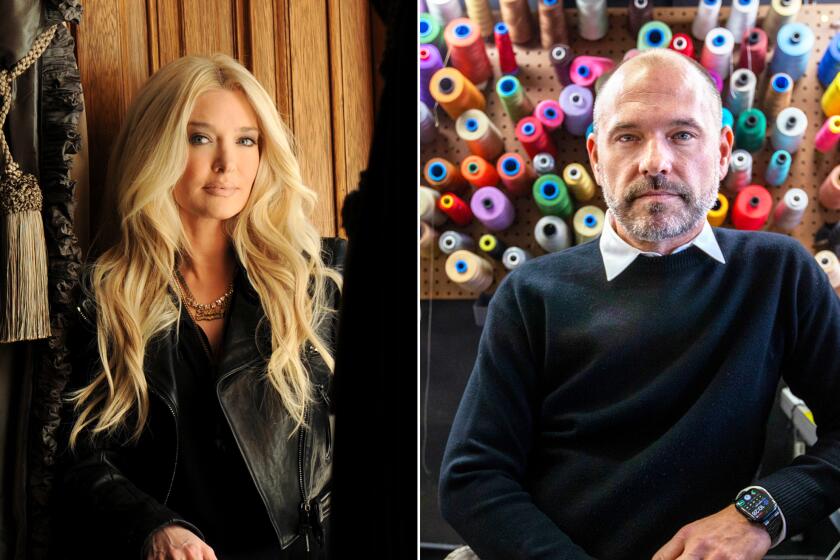

Chris Psaila, co-owner of Marco Marco design firm, said false accusations by Erika Girardi nearly sent him to prison.

Once one of the state’s most powerful lawyers, Girardi is suspected of stealing tens of millions of dollars from clients and colleagues. Now 83, he is bankrupt, facing federal wire fraud charges in two jurisdictions and has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Despite more than a hundred lawsuits against the lawyer and 155 complaints over the decades, the State Bar did not take action against him until March 2021. By then, his law firm had collapsed, and a federal judge had already referred him for criminal investigation related to his misappropriation of millions of dollars from clients.

None of the officials alleged to have inappropriate relationships with Girardi still work for the State Bar, according to the agency. Layton was fired in 2015 but later sued the agency for wrongful termination and received a $400,000 settlement. He did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Bob Baker, an attorney who has represented Layton and at least one other former State Bar employee during the investigation, said Friday that he had not seen the law firm’s report. Asked for comment about the report’s findings, Baker said, “I don’t give a damn,” before ending the call.

The Times previously detailed how Layton functioned as Girardi’s social secretary, emissary to law enforcement and chauffeur while collecting a State Bar paycheck. Girardi provided free legal representation when the Laytons sued their general contractor, and employed two of their children at the Girardi Keese firm, The Times found.

Layton even selected Girardi to be godfather to one of his children, according to the report. Financial records cited by investigators showed payments to the Laytons from Girardi’s law firm dating to 2002. Some payments went to Layton or his wife directly, but more than $460,000 went to “Layton & Layton” between 2006 to 2014. Layton told investigators that the entity provided consulting services to Girardi Keese, mainly by his wife.

Rose Layton told investigators that the payments were “for unspecified services ‘related to the financial aspects of a case,’” according to the report. The investigators said that Rose Layton had no documentation supporting the services she claimed to provide.

From 2013 to 2020, Layton charged an average of $45,000 per year on the American Express card he had, which was paid for by Girardi’s law firm, the report said. Girardi also guaranteed a $150,000 bank loan to Layton in 2006 — while he worked at the State Bar — and the law firm made payments on the loan for several years. In addition, Girardi’s law firm leased two BMWs and a Cadillac Escalade to Layton while he worked at the State Bar and afterward.

Of the cash and valuables Girardi directed to the Laytons, the report said that these “payments and gifts were never properly disclosed.”

Ellin Davtyan, the State Bar’s general counsel, said she could not comment on whether any of the report’s findings had been referred to federal or local law enforcement for criminal investigation.

“Be assured that we have and will continue to take appropriate actions in response to the evidence presented,” Davtyan said.

Other State Bar employees and members of the agency’s governing board also secretly took gifts and other perks from Girardi, the investigators found. The report revealed a previously “not well known” relationship between Girardi and a State Bar prosecutor, Murray Greenberg, who worked at the agency for more than 30 years.

Girardi gifted the prosecutor with meals at Morton’s, invitations to Girardi’s Super Bowl, Christmas and Thanksgiving parties, and tickets to concert performances by Adele and Santana, investigators found. He did not list the presents on disclosure forms as required by the State Bar.

A Girardi Keese employee recalled Greenberg visiting the law firm’s Wilshire Boulevard frequently for closed-door meetings with the powerful attorney. Greenberg, who oversaw the intake department for complaints for years, was involved in closing at least six complaints against Girardi.

In one case, Greenberg instructed a colleague to “make it go away,” according to the report.

When investigators attempted to question Greenberg in January, he invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination, the only witness to do so.

Greenberg retired in 2019 and moved to Arizona. He could not be reached for comment.

Tom Girardi’s downfall prompted a two-year reckoning at the State Bar of California.

Another ally Girardi cultivated at the bar was its former president, Luis Rodriguez, a longtime attorney in the L.A. County public defender’s office. Rodriguez initially dodged investigators’ attempts to question him but agreed after they said they would get a subpoena, according to the report.

He appeared on Girardi’s radio show and traveled with Girardi on his private plane on two occasions while on the State Bar‘s governing board, but according to the report, he told investigators that he was then unaware of any disciplinary cases against Girardi.

“Another witness reported seeing Rodriguez at Girardi’s table at Morton’s, during which time Rodriguez and Girardi discussed Rodriguez possibly serving as the Public Defender,” according to the report.

Bank records at Girardi’s firm showed payments totaling $3,000 issued to a person named Luis Rodriguez between 2012 and 2013. When investigators sought to meet with Rodriguez a second time to ask about bank records, he declined through his lawyers.

An attorney for Rodriguez, Sylvia Torres-Guillén, denied that he had received the funds and criticized the authors of the report for raising “these false documents for the first time in a public document.”

She said that while investigators asked for a follow-up interview, “they refused to provide any information or documentation despite our request for due process.”

Even when complaints against Girardi were referred outside the agency because of acknowledged conflicts of interest, top bar officials and staffers continued to meddle in their handling, the report said. In one cited example, Bob Hawley, a longtime bar employee who rose to the post of interim executive director, “ghostwrote decisions in matters assigned to outside counsel without disclosing the fact, including a decision to recommend closure of a complaint against Girardi,” the report said.

Under questioning, Hawley “admitted to” ghostwriting the materials and claimed that the bar’s trustees were aware of his involvement, but investigators said they found no evidence of this.

The investigators also questioned the outside lawyer whose name was on the decision closing the Girardi complaint. The lawyer, who is not identified in the report, initially “stated unequivocally” that no one else had drafted the memo but backtracked after being shown evidence of Hawley’s involvement. The lawyer acknowledged accepting “what Hawley sent” and that “the decision to close the case was not an independent one.”

Hawley did not respond to messages seeking comment.

The findings of the 16-month investigation were drawn from a review of more than 950,000 documents and interviews with 74 witnesses, some of whom, including Layton, had to be compelled by a state judge to sit for questioning.

The report’s findings prompted state Sen. Tom Umberg (D-Orange) to announce that he would “withhold making any decision on what amount, if any” the State Bar could collect from California’s 260,000 attorneys next year to fund its budget. In an interview, Umberg expressed confidence in the bar’s current leadership but said he needed to “focus the bar’s attention” by threatening its budget.

“If you are suggesting that the Legislature go, ‘Here’s your dough and please, please fix your problems’ — that’s not going to happen,” Umberg said. “I fully expect the bar will demonstrate that it has and will take corrective action,” adding, “This should create additional incentive to do so.”

Duran said in a statement that the “current Board and State Bar leadership is resolute in our commitment to effectuate profound change.” He highlighted several reforms, including the hiring of forensic accounting experts and new rules for the bank accounts where lawyers store client money, which the agency instituted in recent years in an attempt to identify and prevent unethical behavior.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.