California banned affirmative action in 1996. Inside the UC struggle for diversity

- Share via

For nearly half a century, the University of California has been at the center of national debates over affirmative action and who is entitled to coveted seats in the premier public higher education system.

In 1974, after Allan Bakke, a white applicant, was rejected from the UC Davis medical school, he alleged reverse discrimination and sued, becoming the namesake of a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case curbing racial quotas. In 1995, UC regents voted to eliminate affirmative action and one of them, Ward Connerly, championed a successful campaign a year later to pass Proposition 209, the nation’s first ballot initiative to ban consideration of race and gender in public education, hiring and contracting. Over the last decade, California legislators have launched at least three attempts to restore affirmative action in college admissions — all have failed.

As the U.S. Supreme Court opens oral arguments Monday on whether to strike down affirmative action in cases involving Harvard and the University of North Carolina, UC’s long struggle to bring diversity to its 10 campuses offers lessons on the promise and limitations of race-neutral admission practices.

The California takeaway: Nothing can fully substitute for affirmative action practices that allow universities to admit a diverse student body, including using income and parent educational levels as proxies for race. But after passage of Proposition 209 touched off UC’s 25-year slog of trial and error — plus a massive investment of more than a half-billion dollars on diversity measures — a meaningful difference can be made.

“While California has not identified a really effective policy to promote diversity other than affirmative action, it has shown experimentation is beneficial for targeted students,” said Zachary Bleemer, a Yale University assistant professor of economics and research associate at the Center for Studies in Higher Education at UC Berkeley. “And so it’s worth it.”

UC President Michael V. Drake and all 10 chancellors have submitted an amicus brief in support of Harvard and UNC’s affirmative action policies. Calling UC a “laboratory for experimentation” on using race-neutral measures to promote diversity, the university leaders said that decades of outreach programs to low-income students and re-crafted admissions policies have fallen short.

“Those programs have enabled UC to make significant gains in its system-wide diversity,” the brief said. “Yet despite its extensive efforts, UC struggles to enroll a student body that is sufficiently racially diverse to attain the educational benefits of diversity.”

Does the pursuit of admissions diversity by Harvard and the University of North Carolina violate civil rights laws? Supreme Court to decide.

For some private universities, which are allowed to use affirmative action, the looming high court decision is causing consternation. Many experts predict the court’s conservative majority will strike down race-based preferences in a case that could affect not only higher education, but potentially the workplace as well.

“You are talking about the devastation of the American admissions process for students of color, full stop,” said Pomona College President G. Gabrielle Starr. “Affirmation action is hands down the best tool we have for maintaining racial and ethnic diversity in colleges in the United States.”

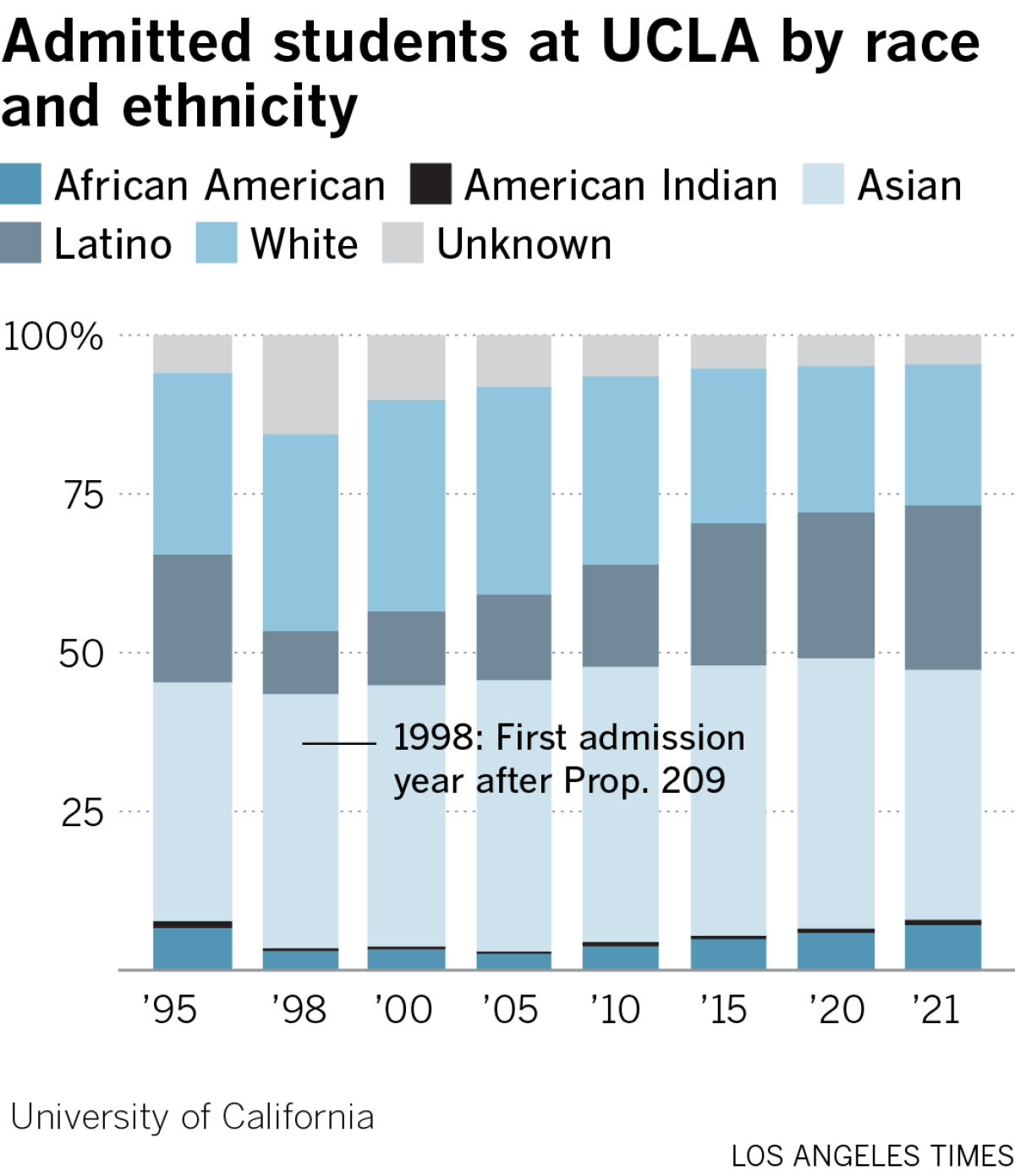

Initially, Proposition 209 drastically reduced diversity at UC’s most competitive campuses. In 1998, the first admissions year affected by the ban, the number of California Black and Latino first-year students plunged by nearly half at UCLA and UC Berkeley. William Kidder, a UC Riverside civil rights investigator, recalled his shock when he entered UC Berkeley law school in 1998 and found that his first-year class of 270 included only six or seven Black students, compared with four times that many in the class two years ahead of him enrolled before Proposition 209.

“The lack of diversity in the classroom had a negative impact on my learning as a student,” said Kidder, who is white. “The range of viewpoints and quality of discussion about ideas were inhibited.”

California State University’s 23 campuses did not lose nearly as many Black and Latino students as UC did, and the system’s enrollment today nearly fully reflects the state’s diversity. Among its 422,391 undergraduates in fall 2021, 47% are Latino, 21% white, 16% Asian and 4% Black.

That closely mirrors the demographics of the state’s 217,910 California high school students who met UC and CSU eligibility standards in 2020-21: 45% are Latino, 26% white, 16% Asian and 4% Black. CSU’s wider access, more affordable price tag and greater ease of commuting from home may be some reasons behind the greater diversity.

But diversity varies, with proportions of Latino and Black students lower at several of the more selective CSU campuses. At Cal Poly San Luis Obispo — with a 31% admission rate in fall 2021 — 53% of undergraduates are white, 19% Latino, 14% Asian and 1% Black. At Cal State Los Angeles — with an 80% admission rate — 72% of students are Latino, 11% Asian, 4% Black and 4% white.

“While Proposition 209 promoted race neutrality in university student recruitment, admissions, financial aid, student academic support and employee hiring, the policy has made it more challenging to erase equity and opportunity gaps that exist in the CSU,” the university said in a statement. “Despite the challenges that have resulted, the CSU has continued to serve significant numbers of students from underrepresented communities over the years and we continue outreach efforts to provide access to students who are Black, indigenous or people of color and provide support once they are enrolled in the university.”

UC enrollment still does not fully reflect the state’s racial and ethnic makeup — falling particularly short with Latinos, who made up just 30% of the system’s 189,173 California undergraduates in fall 2021. Students of Mexican heritage are by far the largest undergraduate ethnic group, however.

But campuses are making notable strides. Black and Latino students increased to 43% of the admitted first-year class of Californians for fall 2022 compared with about 20% before Proposition 209. For the third straight year, Latinos were the largest ethnic group of admitted students at 37%, followed by Asian Americans at 35%, white students at 19% and Black students at 6%.

The push to admit more Californians comes amid demands to narrow entry to out-of-state and international applicants to free more seats for residents.

The enrolled first-year class of fall 2021 was also the most diverse ever, with Black and Latino students making up 38% compared with about 20% in 1995 before Proposition 209.

Progress has been striking at UCLA, where the affirmative action ban hit particularly hard and swift. By 1998, the number of Black and Latino students in the campus’ first-year class of Californians had plummeted by nearly half.

But by 2021, UCLA’s California first-year class included more Black students — 346, or 7.6 % — than their 1995 numbers of 259, or 7.3%. The same is true for Latino students, whose numbers grew to 1,185, or 26%, from 790, or 22.4%, during that same period.

UCLA devotes up to $2 million annually to aggressively recruit diverse students and then convince them to accept their admission offers. In the early 2000s, the UC system launched two major reforms to boost diversity: an admission guarantee to top-performing students statewide and at most California high schools, and a comprehensive review process that uses several factors — including special talents and location of home and high school — in addition to grades and coursework to evaluate applicants.

In 2020, UC regents voted to eliminate standardized test scores as an admission requirement in another landmark step to widen access to underserved students.

“We’re very proud of the progress we’ve made,” UCLA Chancellor Gene Block said in an interview. “We also recognize how far there is to go.”

UC Berkeley also has gained ground, especially since 2019, when the campuses increased fall enrollment of first-year Black and Latino Californians by more than 30%.

But Femi Ogundele, UC Berkeley’s associate vice chancellor of enrollment management, remains frustrated by the affirmative action ban, saying it prevents his team from fully understanding their applicants whose identities are often deeply connected to their race and gender. Hearing how applicants navigated experiences of being the only students of color in their high schools, for instance, or plowing through male-dominated science or technology classes as a girl could provide valuable insight into their character, he said. Proposition 209 barred discrimination on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin.

Some researchers have found that the Proposition 209 ban has had lasting negative consequences.

In a 2020 study, Bleemer found that the ban caused Black and Latino students who might otherwise have gotten into UCLA and UC Berkeley to cascade down into less competitive campuses; others chose not to apply for UC admission altogether. Such UC applicants ended up earning fewer undergraduate and graduate degrees and, for Latinos, lower wages. By the mid-2010s, the effects of Proposition 209 had reduced the number of early-career Black and Latino Californians earning more than $100,000 by about 3%, or as many as 1,000 earners, according to the study.

“This was a sort of a permanent shock to young Black and Hispanic workers,” Bleemer said. “And it didn’t lead to a symmetric boost for white and Asian students who gained access to these universities.”

Others, however, say the takeaway from UC’s experience is positive. Richard Sander, a UCLA law professor, argues that the affirmative action ban led to greater diversity at campuses throughout the system and better grades and higher graduation rates for Black and Latino students.

The University of California plans to offer conditional admission to students who aren’t eligible as first-year applicants as long as they meet course and grade requirements at a community college.

Starr, the Pomona College president, said affirmative action has helped the institution create a diverse class with Black students making up 9% — nearly twice the rate at UC. Latinos are at 16%, Asians 17% and whites 34%. She said that Pomona, one of the nation’s top-rated liberal arts colleges, is looking at ways to even opportunities for applicants if race can no longer be considered. They include possibly rethinking the use of standardized tests, which are now optional, and letters of recommendation — both measures found to favor more privileged students.

At USC, officials are thinking about revving up more aggressive recruiting practices and more generous financial aid packages to maintain diversity. In USC’s 2021-22 undergraduate class, Black students made up 6%, Latinos 17%, Asians 24% and whites 30%.

Campus officials plan to decide by next spring or early summer whether to continue optional testing policies for fall 2024 applicants, said Kedra Ishop, USC vice president for enrollment management.

Ishop said one lesson she learned from her administrative experience at the University of Texas at Austin during multiple conflicts over affirmative action is to be ready to send out clear messages to potential applicants about the value of diversity. “We want a diverse student body on our campus, and we’ll pursue that through whatever the legal means we have after this decision,” she said.

At UC Berkeley, Ogundele said affected universities should “double down” on comprehensive review systems to evaluate a student beyond academic metrics and use data aggressively. Admission officials will need to understand the environment not only in various ZIP Codes but also individual high schools to place a student’s academic experiences in full context, he said.

“I recognize that’s a big ask,” Ogundele said, noting there are hundreds of high schools across California. “But that’s what’s going to be necessary if your process is going to be equitable.”

Block said UCLA is also ready to share its experiences. A precipitous drop in California Black first-year students in 2006 — down to 95, lower even than immediately after Proposition 209 — prompted the campus to refine its comprehensive review system to pay greater attention to an applicant’s learning environment. Then, in 2012, Block hired Youlonda Copeland-Morgan, who reshaped the university’s outreach, recruitment and enrollment strategies. Copeland-Morgan, who retired last month as vice provost for enrollment management, called her approach “intrusive recruiting” to pursue applicants as college coaches do highly prized athletes.

She and her team launched collaboratives with more than two dozen Los Angeles Unified high schools and several African American churches in the Inland Empire to scout promising students and keep them on track, for instance. They look for diverse talent not only at college fairs, but also community events such as the Taste of Soul street festival in the Crenshaw neighborhood. They meet families at Starbucks in Compton, South L.A., Ladera Heights, South Gate. A few years ago, the team started a texting program to students as young as eighth grade to prepare them for college and possible UCLA admission.

As most University of California campuses start classes this month, the acute shortage of affordable housing is pushing many students into desperation, including living in trailers or working multiple jobs to cover high rents.

Over the last decade, the number of Black students from California who apply, are admitted and enroll at UCLA has swelled. Black first-year student enrollment, for instance, grew by more than 100%, from 169 students, or 4.2%, of the 2012 first-year class to 346, or 7.6%, in 2021. Latino enrollment, however, grew only by 19% during that period.

Both UCLA and UC Berkeley admit enough Black and Latino applicants to fill their classes with representative shares, but need more to accept their admission offers. Those rates have grown more quickly for Black students than Latinos.

The campuses say they are reaping big payoffs — 75% commitment rates — by holding in-person activities that connect admitted students with faculty, staff and other students of similar backgrounds.

Block said UCLA is also hiring more Latino faculty and working to become a so-called Hispanic-serving institution, which will open the door to federal grants to enrich Latino educational opportunities. To address family financial concerns, the campus launched a pilot program this year offering low-income students up to $2,000 annually or $10,000 during an undergraduate career to reduce their financial burdens.

How much such measures will help institutions make the transition to higher education without affirmative action is, however, unclear.

Ogundele experienced both worlds as an admissions professional at Stanford University, where he used affirmative action, and UC Berkeley, where it is banned.

“What I’m learning in this environment is that there is no alternative,” Ogundele said. “There is no race-neutral alternative to being able to consider race.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.