Two Times reporters investigated a discredited ex-doctor for allegedly practicing medicine without a license. Wild claims, a restraining order, and a court date followed.

- Share via

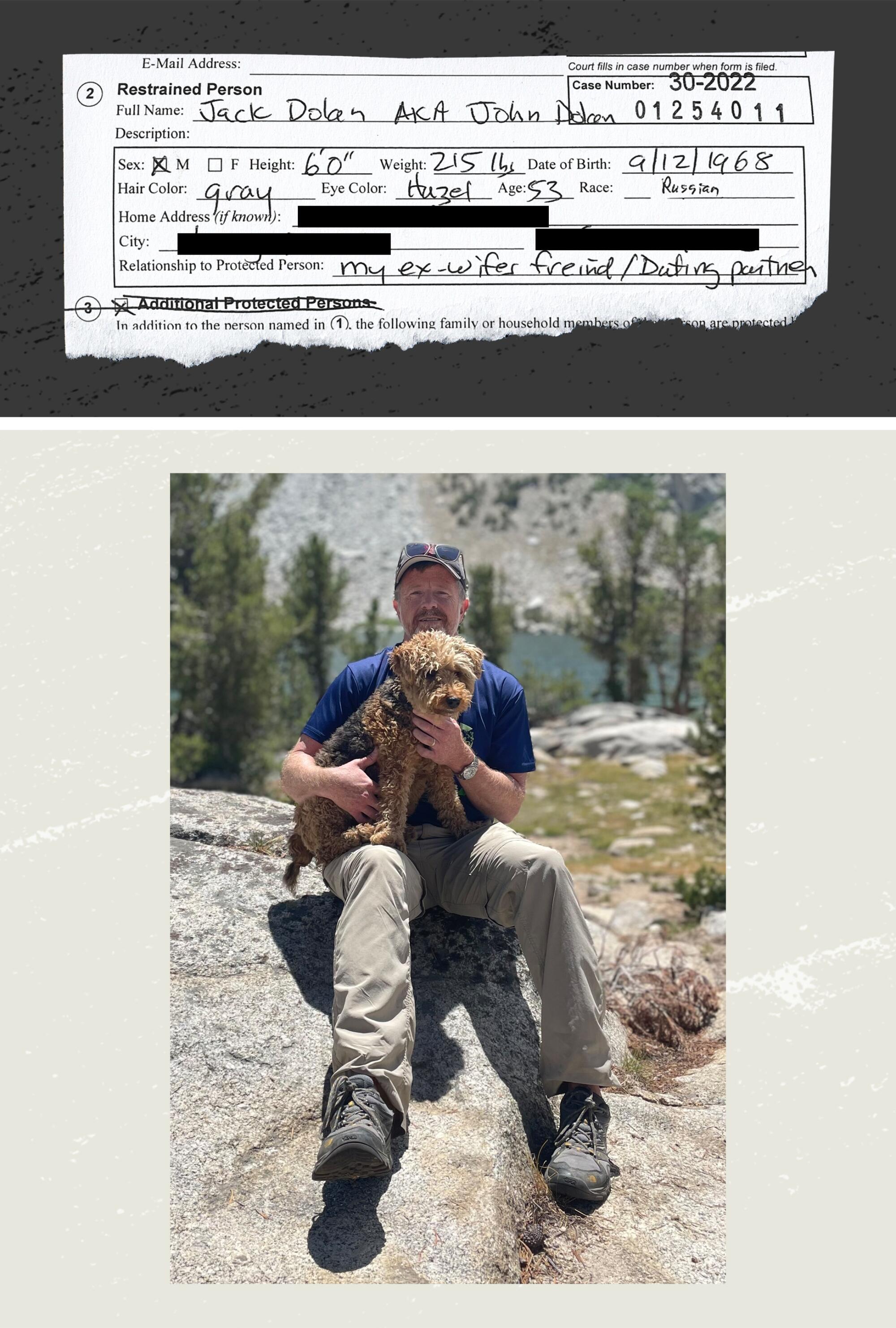

The text message appeared at 10:32 one night in April from an unknown number: “RESTRAINING ORDER FOR JACK DOLAN, AKA BRITTNY MEJIA”.

“Please stop cyberstalking,” it read.

Attached was a court order forbidding contact with Michael Mario Santillanes, a Newport Beach cosmetic surgeon and the subject of a Times investigation by the authors of this story into whether he continued practicing medicine after his license was revoked in 2020.

In his request to the court, Santillanes didn’t mention the people he named were Times reporters. Instead he described being menaced by a Russian thug, Dolan, and he suggested Mejia didn’t exist — claiming her Yelp profile was a fictitious identity created to stalk his former clients.

Based on Santillanes’ claims, the court granted his petition, which temporarily derailed The Times’ reporting. It eventually led everyone involved to a Santa Ana courthouse.

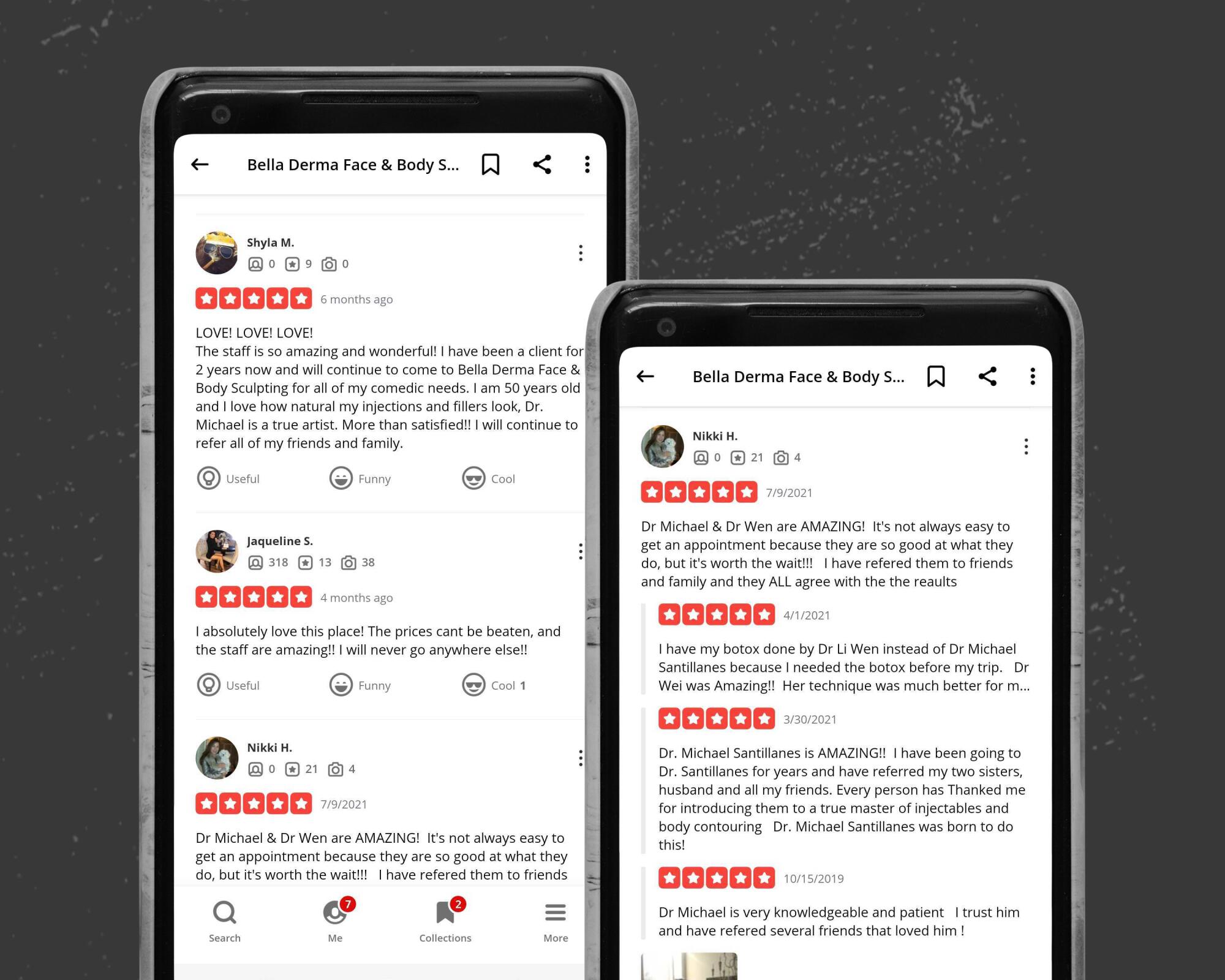

Before receiving the restraining order, the reporters had been in contact with Rien Peccia, Santillanes’ ex-wife, who said she’d reported her claims that he was still practicing to the Medical Board of California. She turned over to The Times emails she sent to the board, with links to Yelp reviews praising his work that were posted long after he lost his license.

- Share via

Reporter Jack Dolan breaks down the circumstances surrounding a restraining order rife with false claims filed against him by former Newport Beach cosmetic surgeon Michael Mario Santillanes. Santillanes had been the subject of a Times investigation by reporters Jack Dolan and Brittny Mejia.

The medical board had been the subject of a series of recent Times investigations looking at its discipline of troubled doctors.

In the last three fiscal years, the board has received nearly 1,000 complaints about people practicing medicine without a license, including doctors who had lost their licenses, board spokesman Carlos Villatoro said. Only three such doctors were referred to local prosecutors, but Villatoro refused to identify them.

Villatoro could not say whether any of the three doctors referred to prosecutors had been charged, let alone convicted, because the board does not track the outcomes of such cases, he said.

Had the board taken any action against Santillanes, based on Peccia’s allegations?

“Complaints and investigations are confidential by law, and as such, the Board has no information to share with you at this time,” Villatoro said.

The Medical Board of California was established to protect patients by licensing doctors and investigating complaints. The board has a long history of going easy on troubled doctors, a Times investigation has found.

A review of medical board records showed that Santillanes faced a long list of accusations before his license was revoked, including that he’d sold prescription drugs to people he hadn’t examined, reused needles from one patient to the next and had drug-fueled, sexual encounters with patients and staff.

Santillanes vigorously disputed many of the allegations. The administrative law judge who reviewed the evidence considered several of his accusers not “credible” and dismissed some of the claims, including those of sexual misconduct.

But the judge found Santillanes had, among other things, prescribed controlled substances to about a dozen people without examining them and been negligent in the care of two patients, performing procedures on one without proper consent.

Much of Santillanes’ testimony also was not credible, his practice “seemed to be in a state of chaos” and he “disregarded the health and safety of patients and the public over an extended period of time,” the judge concluded.

The medical board revoked Santillanes’ license in March 2020.

But that wasn’t the end of the story, according to online reviews for Bella Derma Face and Body Sculpting, the clinic Santillanes founded.

“Dr. Michael Santillanes is AMAZING!!,” Nikki H., from Napa, posted on Yelp in March 2021. She said she had referred family and friends, who thanked her for “introducing them to a true master of injectables and body contouring. Dr. Michael Santillanes was born to do this!”

Shyla M., from Huntington Beach, posted her review at the end of January 2022. “Dr. Michael is a true artist. More than satisfied!!,” she wrote. “I will continue to refer all of my friends and family.”

Santillanes did not respond to emails requesting comment for this story, including questions about the Yelp reviews.

On March 30, as Mejia reached out to reviewers to determine when they’d seen Santillanes, Dolan went to the clinic, where he spotted a man resembling Santillanes walking out to the parking lot at closing time wearing beige surgical scrubs.

Asked if he was indeed the doctor, he said “no” and that Santillanes “doesn’t work here anymore.” Asked again if he was Santillanes and practicing medicine without a license, he said he was an “orderly.”

- Share via

Times staff writer Jack Dolan questions Michael Mario Santillanes as he is leaving Bella Derma Face and Body Sculpting clinic in Newport Beach.

That night, Mejia heard back from one of the reviewers who agreed to speak on the phone. The woman, who asked not to be identified, said she’d been seeing Santillanes since around 2018. She said he’d just given her lip and facial fillers over the winter, in December 2021 or January 2022.

Recently, the woman said, Santillanes had been trying to direct her to another doctor — Li Wen, whom Santillanes described in a court hearing as his protégé and who is now listed as the owner of the clinic. But the patient said she insists on being treated by Santillanes.

A doctor whose license is revoked can still provide Botox and filler injections. But they would have to obtain a nursing or a physician assistant license and be supervised by another licensed doctor.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Times reporters searched for other healthcare licenses issued to Santillanes and found none. Villatoro said the medical board ran a similar search, “which did not reveal any active license for [Santillanes].”

During that reporting, the temporary restraining order was granted on April 11.

In supporting documents explaining why he wanted protection, Santillanes failed to mention that Dolan had identified himself as a Times reporter.

He described Dolan — who is 5’ 8”, 170 pounds and Irish — as a violent, 6-foot, 215-pound Russian who was dating his ex-wife.

At that point, Dolan had never met Peccia in person.

Santillanes’ motion didn’t mention the attempt to interview him in the parking lot of his clinic, but did claim Dolan had shown up at his house later that evening, banging and kicking his front door.

“Im going to f— you up, Im gonna break the door down, and then you will come running out like a bitch,” Santillanes said that Dolan shouted.

Then, he said in the documents, Dolan had shown up around a week later at the clinic to berate his former colleagues.

“Im going to destroy this business, and make sure you lose your job, because all you guys are going down,” he said that a slurring Dolan shouted at the receptionist.

Based solely on the story Santillanes told her, Judge Sandy N. Leal granted the order prohibiting Dolan from coming within 100 yards of Santillanes or his workplace and from making any attempt to contact him.

Such orders typically are sought as immediate relief, protecting someone from violence, threats or harassment.

After receiving a copy of the order, The Times filed papers pointing out the falsehoods and omissions in Santillanes’ tale and the order was lifted, but a hearing to resolve the matter was scheduled a few weeks out. As the court date approached, the two sides exchanged exhibits.

The Times submitted evidence that Mejia used her personal Yelp account to contact patients who left reviews for Santillanes long after his license had been revoked. She’d identified herself as a Times reporter.

Santillanes submitted a video he said came from a security system at his Huntington Beach house to bolster his allegation that Dolan had pounded on his door and issued threats.

The video clip had no sound and is a view from inside Santillanes’ house. It shows Santillanes sitting alone on his couch in shorts, fixing his hair and sipping from a mug. At one point he motions as if he hears a noise outside. He peeks from behind some curtains and then heads to the door to hold it shut, first with a hand and then with a foot.

He then bars the door with a chair and fetches a cell phone. He opens a hatch at eye level on the door and gestures as if he’s arguing with someone outside, who is not visible.

No one else appears in the video, which began at 6:39 p.m., according to the time stamp, and lasts about three minutes.

Dolan was grocery shopping in Long Beach at the time, backed up by an electronic bank record and the Gelson’s receipt.

Dr. Michael Santillanes alleged Jack Dolan pounded on the door to his house and issued threats. Jack was at a Gelson’s at the time, messaging his wife about dinner.

Santillanes had also sent the court two threatening emails he said he received from Peccia on March 28, two days before the parking lot encounter.

“I told Jack where you live and work. He’s gonna f— you up and write some crazy nasty s— so you will know how it feels to have your life ruined,” one of the emails read.

The other said, “You sound jealous of Jack. Trust me, he is much more sexier, sweeter, romantic and thoughtful than you ever were as a partner.”

Peccia confirmed for Times lawyers she had never dated Dolan and that the two had never met in person. She also said she never wrote those emails. They appeared to come from an old account she had while she was married to Santillanes, she said.

Serious malpractice leading to the loss of limbs, paralysis and the deaths of patients wasn’t enough for the California Medical Board to stop these bad doctors from continuing to practice medicine.

During the court hearing in early May, Santillanes acknowledged accessing Peccia’s email in the past without her authorization and said he didn’t think that was a crime if the parties were married.

After asking Santillanes about the origin of the emails, the judge pronounced the messages “highly suspicious” — just like the home video she described as “staged” and “overly acted.”

A Times attorney asked Santillanes about a recent breach of The Times’ computer system the day after he filed for the restraining order.

Dolan’s direct deposit paycheck was rerouted from his bank to a financial institution headquartered in Sioux Falls, S.D., and was transferred to a pre-paid debit card. His L.A. Times email account had also been illegally accessed more than a dozen times from IP addresses on the East Coast.

Asked if he was aware of the breach, Santillanes said, “I wish I was that tech savvy, but I wouldn’t even know how to do that.”

The hearing in Orange County Superior Court lasted the better part of two days. Santillanes was on the stand for most of that. None of the other people he claimed were harassed appeared to testify.

The California Medical Board has reinstated a number of doctors who sexually abused patients, a Times investigation found.

When Times’ lawyer Alex Porter asked Santillanes whether he had been practicing without a license, Santillanes’ attorney Dan Knowlton objected, claiming the question seemed designed to help The Times “build” an article about him.

Leal took over the cross-examination and asked Santillanes why, specifically, he had been at the clinic on the day Dolan tried to interview him.

The other doctor there, Wen, is his personal physician, Santillanes said, and he had visited her for medical treatment he didn’t want to describe, citing privacy concerns. He also stopped by to help her with some medical equipment, he said.

Wen did not respond to requests for interviews from The Times.

When Santillanes finished making his case, the judge stopped the proceedings. She cited omissions and inconsistencies in Santillanes’ story and accused him of attempting to mislead the court before dismissing the case and permanently dissolving the restraining order.

Leal invited the Times to file a motion requesting that Santillanes be required to pay the paper’s legal costs and warned Santillanes that if any of the documents he submitted turned out to be false, she would “consider that in any form of sanction.”

Resources are available, but checking your doctor’s track record can be difficult. Here are some tips.

On July 11, the judge granted The Times’ motion for $117,000 in attorney’s fees and costs. Neither Santillanes nor an attorney representing him appeared at the hearing.

In his nearly 15 years handling legal matters for The Times, General Counsel Jeff Glasser said he’d never encountered someone attempting to use the state’s civil harassment restraining order process — designed to protect the vulnerable from violence and stalking — to stop a news story.

“I was concerned that it posed a danger to our newsgathering,” Glasser said.

During his testimony, Santillanes said he’d recently filed an application with the state medical board to get his license back. Board spokesman Villatoro declined to comment on the status of the application.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.