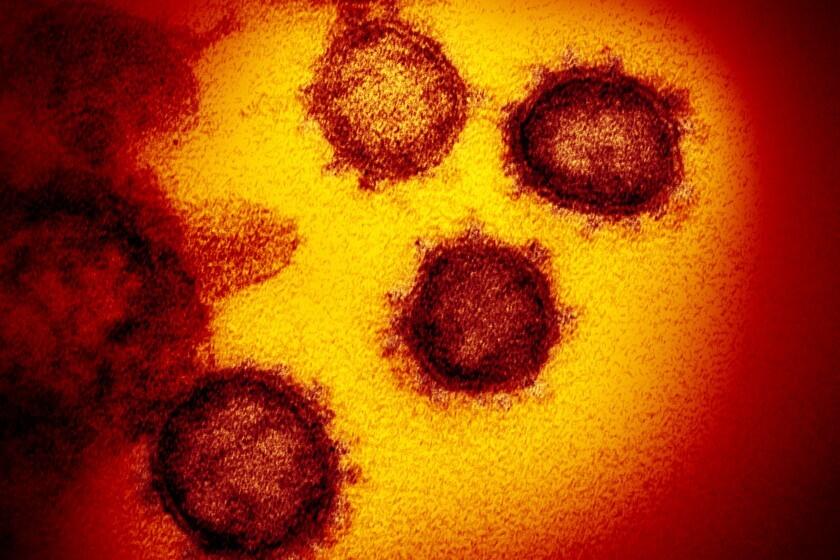

New Omicron subvariants in California bring new questions about coronavirus outlook

- Share via

The upward track of California’s coronavirus case rate may be easing, but contradictory data are muddying the state’s outlook as a new pair of Omicron subvariants seen in South Africa are increasingly making appearances here.

The case rate dipped 6% over the past week, from 15,800 new cases a day to 14,900, according to a Times analysis of state data released Tuesday. On a per capita basis, California is recording 266 coronavirus cases a week for every 100,000 residents. A weekly transmission rate of 100 cases or more per 100,000 is considered high.

But some health officials are not convinced the decline will stay consistent in the coming weeks.

In Santa Clara County, Northern California’s most populous and home to Silicon Valley, the new case rate has fallen 7% in the last week. But wastewater data show that coronavirus levels are actually continuing to rise.

“While it looks like it may be plateauing, it actually isn’t,” Dr. Sara Cody, the county’s public health director and health officer, said Tuesday.

In looking at wastewater data — an indication of future case rates — “every time we see one of those dips, and we can imagine, ‘Oh, maybe we’re on the way down,’ it goes back up. So we are not yet on the way down,” Cody said.

California has reported a 12% dip in daily cases, its first week-over-week decrease in coronavirus cases in two months.

It’s possible the recent plateau is caused by a lag in reporting over the Memorial Day weekend. It also is plausible that transmission will worsen because of gatherings to celebrate the beginning of the summer holiday and the end of the school year and increased vacation travel.

Nationally, what appeared to be a reduction in cases has flattened. The U.S. was reporting about 105,000 new cases a day for the seven-day period that ended Tuesday, about the same as the prior week.

Santa Clara County has the highest case rate in California — 401 new cases a week for every 100,000 residents — followed by San Francisco (400) and neighboring San Mateo County (392), according to The Times’ coronavirus tracker.

The emergence of yet another succession of new Omicron subvariants may prove to be a new wild card in the pandemic.

In March, the nation’s dominant Omicron subvariant was BA.1.1; by April, it was the more contagious BA.2; and by the end of May, it was the even more contagious BA.2.12.1. Now, BA.4 and BA.5 are starting to show up in noticeable levels nationwide.

BA.4 has been detected in Santa Clara County, and “this is the subvariant that caused explosive growth in South Africa,” Cody said. BA.4 and BA.5 are still rare in Los Angeles County, but there have been small increases recently, especially for BA.4.

“The increases in BA.4 and BA.5 have also been seen across the state,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said last week. “We will monitor these increases to see whether these new sublineages, known to be highly infectious and evade some of the vaccine protection ... [will] take hold in our communities by crowding out the other dominant strains.

“As we continue to see growth of the more transmissible variants in the county, we are mindful about the need to use sensible safety measures to reduce risk,” said Ferrer, who has urged residents to get up to date on vaccinations and boosters and wear masks in indoor public settings.

The Omicron strain of the coronavirus keeps generating new subvariants. Here’s a look at how they stack up.

Compared to the prior week, coronavirus case rates fell by 3% in San Diego County, 9% in Orange County, 2% in Riverside County and 21% in Ventura County. Case rates increased by 9% in San Bernardino County and 3% in Santa Barbara County. All counties were considered to have high transmission rates.

Elsewhere in the state, case rates also declined, falling 6% in the San Francisco Bay Area, 2% in the San Joaquin Valley, 9% in Greater Sacramento and 11% in rural Northern California.

But in L.A. County, the case rate was up 10% from the week before, following about a week-long period where it seemed as if cases had flattened or started to decrease. The state’s most populous county was averaging about 4,900 cases a day, or 341 cases a week for every 100,000 residents.

Coronavirus-positive hospitalizations, meanwhile, are continuing to rise, though they remain at relatively low levels compared to earlier surges. On Tuesday, there were 2,601 coronavirus-positive patients in California’s hospitals, up 14% over the past week. The latest number is still lower than the lowest point observed between last summer’s Delta wave and the start of the Omicron surge around Thanksgiving.

A significant percentage of hospitalized coronavirus-positive patients are being for treated for reasons unrelated to COVID-19. And COVID deaths have remained relatively low and stable in California, averaging about 25 a day.

Officials are deciding how best to respond now that COVID-19 cases are rapidly rising after plunging in the spring.

Still, Cody and others say increasing numbers of coronavirus-positive patients can strain hospital systems because they need to be isolated and have extra care and specialized staffing.

Hospitalization trends vary by state. New coronavirus-positive hospital admissions are declining in New York and New England but climbing in the Southeast, including in Florida, and elsewhere in the Western U.S., such as in Washington, Oregon, Arizona and Nevada. Nationally, new weekly coronavirus-positive hospitalizations are up 6% over the prior week.

Santa Clara County last week was designated by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as having a high COVID-19 community level, at which the federal agency recommends universal masking in indoor public settings. The CDC showed the county with 10.1 new weekly coronavirus-positive hospitalizations for every 100,000 residents, just above its threshold of 10 or more for high community level.

But unlike neighboring Alameda County, Santa Clara County has not ordered a new universal indoor mask mandate. Alameda County, which is home to Oakland, became the first county in California to reimplement a universal indoor mask order last week following the winter Omicron wave. The mandate does not apply to Berkeley, which has its own public health agency.

Ferrer also has continued to express concern about rising rates of hospitalizations in L.A. County.

The Biden administration announced Tuesday that each U.S. household can order eight free at-home test kits, on top of the eight previously made available.

On Thursday, the CDC said there were 5.3 new weekly coronavirus-positive hospitalizations for every 100,000 residents in L.A. County, an 18% increase from the prior week. At that rate, the county could pass the CDC’s threshold by the end of June, triggering the recommendation for universal indoor masking. Ferrer has long said that if L.A. County reaches that threshold, a new local universal indoor mask order would be issued for people 2 and older.

The most significant impact hospitals are currently reporting is workers being out sick, Cody said. “What we’re not seeing so far with this wave is a lot of people who are getting seriously ill and requiring hospitalization for their COVID infection. Of course, we’re seeing some of that, but not in the dramatic way that we’ve seen in other waves.”

This latest stage of the pandemic is very different from the first waves, in which hospitals were full of patients on ventilators, Cody said. The latest variants are far more contagious, now spreading almost as easily as measles, “which is pretty stunning,” she added. In addition, the rapid mutations that lead to other subvariants are also making it harder to forecast what will happen next.

Just because deaths aren’t increasing now doesn’t mean that won’t happen in the future, Cody said. While much has been said about the first Omicron subvariant being relatively mild compared to last summer’s Delta variant, more people have died during the Omicron surge and far more people were infected.

“The subvariants that are circulating keep changing and evolving. It’s not just one, it’s multiple,” Cody said. “And I don’t really know what that’s going to look like over time.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.