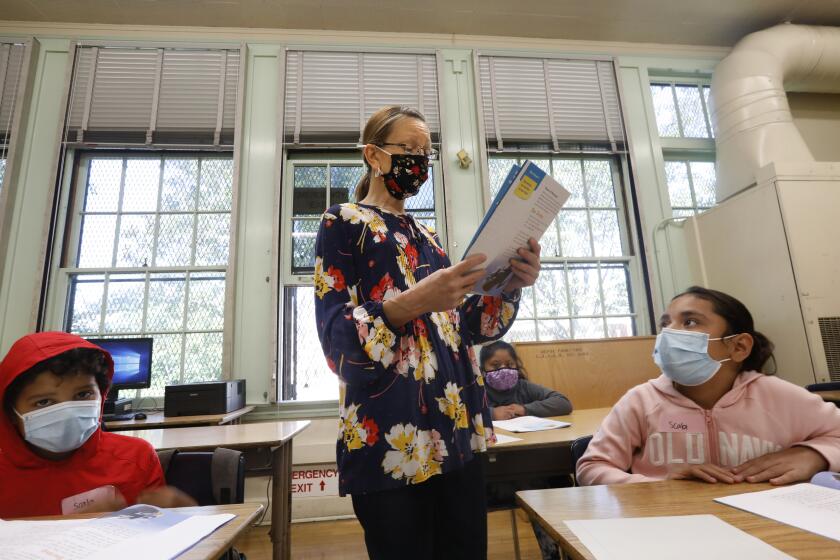

L.A. teacher shortage crisis hits poor kids hardest, forcing a last-ditch staffing effort

- Share via

With less than two months left in the school year, many of Los Angeles Unified’s highest-needs campuses remain significantly understaffed, impeding academic recovery and prompting Supt. Alberto M. Carvalho to redeploy personnel who hold teaching credentials back into the classroom.

The district’s teacher shortage — a deepening problem in California and nationwide — has hit hardest at schools in parts of South L.A. and several other low-income neighborhoods, according to a report by Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, a nonprofit group that manages schools in underserved communities. Fueled by a record $20-billion pandemic-aid-enhanced budget this year, L.A. Unified had promised a hiring spree unseen since the late 1990s, with thousands of new teachers, counselors and other workers who would help lift students from struggles after a year of distance learning and pandemic hardships.

For the record:

5:35 p.m. April 20, 2022An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that L.A. Unified had filled 234 of its classroom vacancies. The district has 234 vacancies left to fill.

The additional 6,000 hires announced last summer included psychologists and psychiatric social workers, teachers, school nurses and custodians. By November, about half of those positions were unfilled, the Partnership report found. Among the 15 schools with the highest number of vacancies, 10 were part of the district’s much-touted Black Student Achievement Plan, according to the March report.

Although hiring progress has been made throughout the year, officials have remained concerned about the lack of teachers, Carvalho said. He said half of the 420 vacancies that remain are in high-needs schools with vulnerable student populations.

Carvalho, who took over in mid-February, has taken a stopgap action to fill the void with credentialed employees who do not work in classrooms.

“Considering the impact that the pandemic has had on students’ ability to learn, we can ill-afford to have these students without credentialed teachers in front of them,” he said this week. “The solution resides within our own workforce. There are plenty of credentialed individuals that can — at least for the rest of this year, and we can make decisions going into next year — return to the classroom and teach students.”

His short-term solution will allow those who fill vacancies to return to their jobs when classroom positions are filled permanently, Carvalho said. He expects next year to begin with appropriate staffing levels as the district increases hiring and retention efforts. The district has 234 of the vacant positions left to fill, Carvalho said.

Lourdes Lopez, the mother of a fourth-grader at Main Street Elementary School in South Los Angeles, said her daughter’s class — a combined third- through fifth-grade room serving students with special education needs —was disrupted when one teacher’s four-month leave touched off a staffing scramble. On days when a substitute teacher could not be found, some of the school’s youngest students would be sent to her daughter’s classroom.

“It became just a day care,” she said, “because what are the kindergarteners and first-graders going to learn? What the fifth-graders are learning?”

Lopez said she supports Carvalho’s plan to move staff to help — although it’s too late to help her daughter.

In a statement, United Teachers Los Angeles President Cecily Myart-Cruz said the district’s initiative is another sign that it needs to do “everything they can” to retain educators and improve teaching conditions during an “unprecedented shortage that’s reached an emergency level.”

“We need to support our students with stability and investment,” she said.

Chase Stafford, vice president of policy and planning for the Partnership, said his organization is worried and is pushing bold solutions for what has been a long-entrenched problem: high teacher turnover and disproportionate vacancy rates in schools serving the poorest urban neighborhoods.

“We were particularly concerned as to where the vacancies were concentrated,” Stafford said. Among its proposed long-term solutions — which include improving workplace conditions and financial incentives — the organization has asked L.A. Unified to limit hiring at easier-to-fill low-need schools until staff-to-student ratios are fulfilled at high-need schools.

April and May are critical months when it comes to hiring for the next school year, Stafford noted. Although Carvalho’s plan addresses the needs of the moment, the organization wants the district to plan for next year by prioritizing hiring at high-need schools.

“Realistically, you won’t be able to hire for all the positions,” Stafford said. “We want every student in LAUSD to have access to a great education, but if we don’t reckon with the fact that there’s an uneven playing field to start with … we know how it’s going to play out.”

Carvalho did not go as far as to say he would freeze hiring at low-need schools, but he acknowledged the challenges some schools face.

“We have a long history in this district of having the same schools, in the same ZIP Codes, reflecting the same communities, of not being able to fill positions within an adequate timeline,” Carvalho said. “We are the agents of equity. So it is our responsibility to ensure that that needle moves in the direction of highest-need first.”

LAUSD’s pandemic recovery hiring spree is thousands of new staffers short of its goal to provide critical mental health and academic support.

School board member Tanya Ortiz Franklin said she has felt the shortages at high-need schools in her district, where key positions like math and science teachers have remained unfilled. At one elementary school in South L.A., a staff member told her they covered classrooms three times a week, which left her no time to work on her own responsibilities.

“I have felt this acutely because my schools have felt this acutely,” said Ortiz Franklin, who represents schools in San Pedro, South L.A. and Watts. “It has only exacerbated the challenges that schools in high-need areas have always felt. … The dollars brought a lot of hope, and then that hope wasn’t necessarily fulfilled.”

The district’s operational shortcomings have also made for hiring delays, Ortiz Franklin said, including a human resources staff that has not grown despite the increased number of open positions. But Ortiz Franklin said she is hopeful about Carvalho’s plan.

“He’s making a big move that has been done for short-term [situations], like Omicron and the [teachers’] strike, but to say that we’re going to prioritize classrooms for the next [two] months — it seems like it should have been an easy decision, but it’s courageous,” Ortiz Franklin said.

While the hiring spree was well-intentioned and aimed at helping students after the challenges of remote learning, many existing teachers moved into newly created out-of-classroom support positions, exacerbating the teacher shortage, school board President Kelly Gonez said.

“There has been progress made,” Gonez said. But “combined with so many other districts hiring at this moment, and the nationwide teacher shortage, that has meant that filling the underlying vacancies has been much more difficult.”

L.A. school officials have more money than they imagined to make lasting academic progress. Can they meet the challenge to help students recover from pandemic school closures?

Carvalho’s plan to staff classrooms for the remainder of the year, while not ideal, is “better than the status quo,” she said.

“While I think there’s urgency to fill those positions now with credentialed staff, we have to be thinking about next school year and address systemic challenges that impact students in highest need communities,” Gonez said.

Elmer G. Roldan, executive director of Communities in Schools of Los Angeles, said he agreed that the “Band-Aid solution” is much needed. Some school staff have gotten creative by bringing on long-term substitutes, having administrators step in to instruct classes or combining classrooms to cover vacancies.

“At the end of the day, the students are the ones affected by this,” Roldan said. “The quality and the consistency of who is instructing them is so inconsistent, that the learning is impacted.”

Carvalho said that, going into next year, the district is analyzing enrollment data to adjust staffing levels while also accelerating recruitment at local colleges and universities and among retired educators, and increasing outreach to teachers of color, particularly Black men.

At high-need schools, Carvalho said, the district will focus on improving workplace conditions and supporting teachers with professional development to improve retainment efforts.

“This district has moved absolutely in the right direction in terms of compensation strategies in partnership with organized labor, and we’re looking forward to returning to the table to ensure the continuity of that promise to the teachers of our community,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.