California backs syringe programs. But they’re nowhere to be found in Orange County

- Share via

Ronnie Warn was bewildered when he spotted the sign on the door of the Santa Ana office where he routinely brings used needles and picks up clean ones.

The Harm Reduction Institute was closed, it said, “due to unforeseen circumstances.”

Warn turned away from the homey building on 4th Street and tried to calculate how long his supply of clean syringes would last him. Decades earlier, the 60-year-old had first gotten hepatitis, the enduring result of turning to a used syringe when he was desperate.

“When you’re sick on heroin, you don’t care about the needle being dirty,” Warn said. “You take a chance, because you want to get well.”

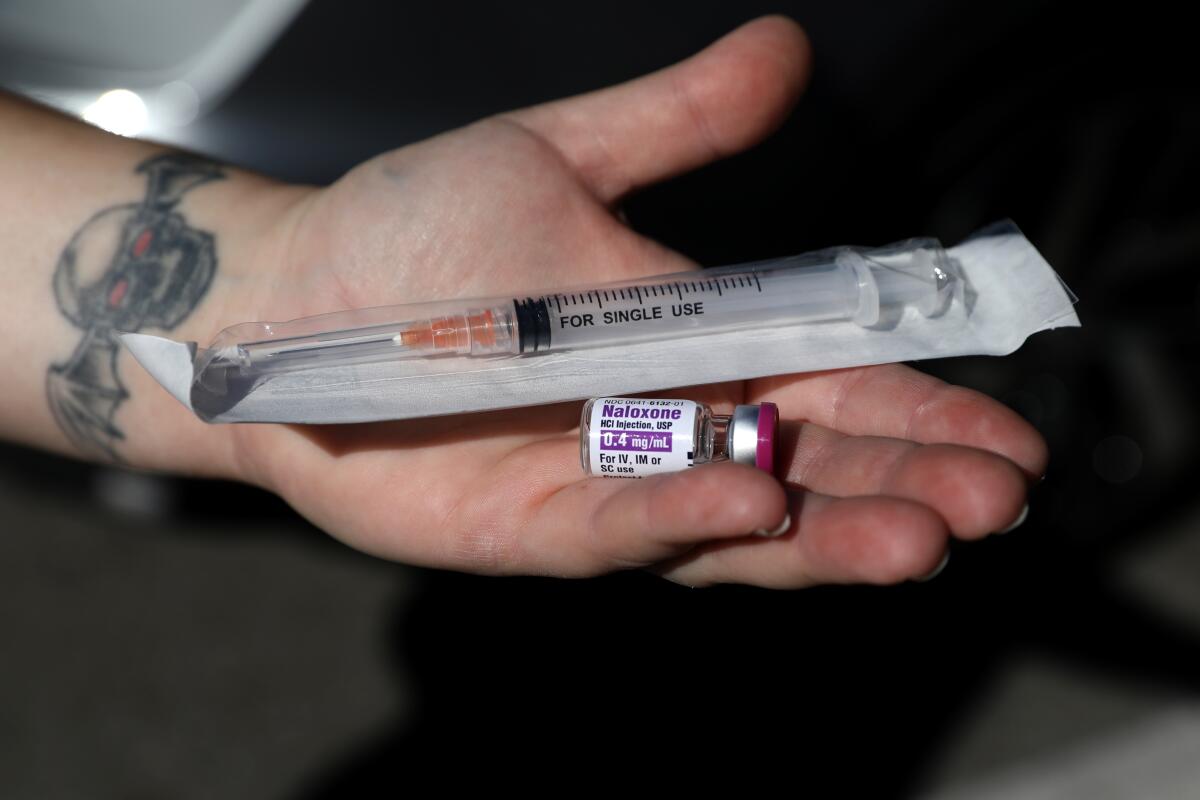

Outside a Santa Ana methadone clinic on a Thursday, he greeted Harm Reduction Institute workers who handed him a backpack loaded with supplies. Shampoo. Oranges. Socks. A plastic bag with naloxone to reverse an opioid overdose.

But no packs of needles. “When they run out,” Warn said, “I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

Orange County has been a perennial battleground for the fight over syringe programs, which are backed by state and federal health officials as a lifesaving tool but have been anathema to some local governments and other critics who denounce them as a hazard and nuisance.

As it stands, Orange County is the biggest county in the country without a program providing syringe access, according to the California Department of Public Health. The Harm Reduction Institute, then part of the American Addiction Institute of Mind and Medicine, halted operations at its Santa Ana offices earlier this year.

After Santa Ana yanked its occupancy certificate, workers with the program hit the streets to hand out naloxone and other supplies, but they could not distribute packs of clean syringes.

With the needle program closed, people are “using whatever they can. Whatever they have,” said Steven Woodson, 51, a program volunteer who said he takes methadone to keep away from heroin. “They’re going to do whatever they’ve got to do. That’s the horrible part.”

Many of the Harm Reduction Institute’s clients are homeless, which means it can be hard to find them on the streets as they are shunted from place to place. Carol Newark, its clinical operations director, said that not having a consistent place for people to access syringes has also “really put a damper on our efforts to try to get people into treatment.”

New York is combating opioid overdoses with places where people can use drugs openly — a first in the United States.

California officials have long tried to pave the way for programs that give clean needles to drug users, championing them as a proven way to clamp down on HIV and hepatitis infections. And opponents have long tried to thwart them from operating.

Protesters have rallied against people handing out syringes in Chico. Police have gone undercover to investigate them in Eureka. The battles have endured in city halls and in the courts.

State officials said that in the last five years, the number of syringe programs across California has jumped more than 60%. But whether Californians can readily access clean, free needles still depends heavily on where they live.

In California, “you’re seeing growth into regions where there really wasn’t a history of these services,” said Savannah O’Neill, associate director of capacity building for the National Harm Reduction Coalition. That is “one of the reasons that opposition is coming up in the way it is now.”

Los Angeles County has at least nine syringe programs listed on a state directory, while vast stretches of the state have none. The National Harm Reduction Coalition estimates that nearly 40% of California syringe access programs are the only ones in their county, while 22 counties have none at all.

California is “caught in a somewhat delicate balancing act,” said Peter Davidson, associate professor in the global public health division at the UC San Diego Department of Medicine. Public health officials know that research shows that “from a public health point of view, there’s nothing not to like.”

But “they’re also very aware that for a lot of communities, their immediate and instinctive reaction is, ‘Oh, hell no,’” Davidson said, and “there’s no point in them forcing some community to open a needle exchange if the local community is going to react in ways that stop it working.”

Four years ago, Santa Ana turned down a syringe program that had operated at its civic center for a permit, contending that it had littered the downtown area with discarded syringes.

It was supportive when Orange County successfully sued to prevent a mobile program from handing out needles there. And it is one of several cities in Orange County and across the state that have banned syringe exchanges.

“There’s a gap between what you think will work in theory and what actually happens in practice,” Councilman Vicente Sarmiento said at a meeting more than a year ago, as Santa Ana council members prepared to vote on that ban. He complained that other Orange County cities had not stepped up to offer the same services.

“It really is unfair that we shoulder the responsibility of being the experiment, in the county, for things that just don’t seem to work,” said Sarmiento, who has since become mayor of Santa Ana.

Sarmiento, who declined to be interviewed, said in a written statement that Santa Ana had revoked the occupancy certificate for the 4th Street program because counseling services were not permitted in that area. The mayor said that Santa Ana “understands the need for counseling and drug treatment services and fully supports these services being provided, but only in areas where it is permitted under city code.”

Neighbors said that in November, a petition against the program was sent to the city, arguing that it drew drug users to the area. “Armed with clean needles, many wander into the neighborhood to shoot up,” it said. “They then discard used needles on sidewalks, in front yards, and in Saddleback View Park,” where children play.

Desi Reyes, chair of the Saddleback View Neighborhood Assn., said that many in the neighborhood sympathize with the plight of people addicted to drugs, but most believe the institute should be relocated away from residential areas.

“We understand the need of it,” he said. “But the neighborhood has really been impacted negatively.”

The American Addiction Institute of Mind and Medicine argued it was a medical provider allowed in the area. The Harm Reduction Institute said it was unaware of the neighborhood petition, but Newark said the program had been stationing someone outside to make sure clients did not linger and had been doing weekly cleanups in the area.

Public health officials have pointed to studies showing that syringe litter is worse in areas without needle exchanges and that shutting them ramps up the risk of HIV and other infections. When an earlier program closed in Santa Ana, an independent researcher contracted by the California Department of Public Health found that risky behaviors were a problem with sterile syringes in short supply and that litter was likely to worsen.

Dr. Kyle Barbour, one of the founders of the Orange County needle program that once operated in the Santa Ana civic center, argued that syringe litter long predated their program and has been tied to a web of other issues, including people fearing police harassment if they are found with their used needles.

Santa Ana officials “just don’t want the program to exist,” Barbour said. “They want to plug their ears, close their eyes and pretend that people don’t inject drugs in their community.”

California has repeatedly tried to smooth the way for syringe programs: Roughly a decade ago, state lawmakers empowered the California Department of Public Health to approve needle exchanges, giving programs in leery cities another route to approval.

When Orange County and other jurisdictions successfully sued to stop syringe exchanges under the California Environmental Quality Act, legislators carved such programs out of the environmental law, to the chagrin of groups that had sued over needle litter and other alleged impacts.

California “has created a situation where the local programs operate separately from what’s happening here in the community without any sort of review” of how they affect the area, said attorney David Terrazas, who represented a neighborhood group and residents who sued over a needle program in Santa Cruz County.

Among their concerns was that the program, run by the Harm Reduction Coalition of Santa Cruz County, did not require that syringe users turn in the same number of needles as they got. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that limiting syringes to one-to-one exchange is less effective in preventing infections and has not been shown to reduce litter.

The Santa Cruz program fended off a key part of a legal challenge after the state exempted syringe exchanges from the environmental law, but it is still facing court claims in the same case that it poses a nuisance.

Harm reduction advocates say that many programs are so sparsely funded that it can be daunting to fight in court: In California, the average needle access program has three staffers and operates on an annual budget of $330,000, according to the National Harm Reduction Coalition.

“They just wear people down,” said Denise Elerick, founder and services coordinator for the Harm Reduction Coalition of Santa Cruz County. “They are going to hit on the left and hit on the right. They will not stop.”

As deaths from drug overdoses have soared, many experts, advocates and lawmakers have promoted an idea still fresh to the United States: giving people a safe place to inject drugs under supervision.

The state also allows physicians or pharmacists to provide clean needles without a prescription under its business code, which is how the Harm Reduction Institute said it had been operating in Santa Ana — not as a syringe exchange but as a clinic run by a licensed physician.

The California saga over syringe programs is epitomized by Chico, where a needle exchange was authorized by the state three years ago and soon met with public protests. Then came a lawsuit under the California Environmental Quality Act, which ultimately led to a settlement that halted the needle program.

When it shut down, “we got calls from Sacramento saying, ‘What the hell happened? We’re having all these folks from Butte County come down’” for syringes, said Marin Hambley, board chair of the Northern Valley Harm Reduction Coalition. “It caused so much harm to our community to end services.”

Chico subsequently banned syringe exchanges, but after roughly 10 months of being shuttered, the group reopened a syringe program under the authority of physicians who volunteer their time.

Harm reduction advocates caution, however, that is rare to find doctors who can operate a consistent program. In Chico, for instance, syringes are only available on Friday mornings when the doctor is in, although other services such as syringe disposal are available all week, Hambley said.

When the program reopened, one Chico council member called it “incredibly disrespectful.”

“The reckless endangerment that this program causes our community will not be tolerated,” then-Chico Council Member Kami Denlay told the Chico station Action News Now.

In the face of cities like Santa Ana and Chico banning needle programs, California recently jettisoned a requirement for syringe exchanges authorized by the state to operate in line with local ordinances. State officials said in February that so far, no syringe program had sought state approval in a city that bans them.

The Santa Ana program could change that: In March, the Harm Reduction Institute said it had decided to stop operating as a program overseen by a doctor at the American Addiction Institute of Mind and Medicine, and instead pursue state approval as a syringe exchange. The Santa Ana ban on needle exchanges “has no force or effect” after California changed its rules, its attorney argued in a letter.

In the meantime, institute outreach coordinator Gino Lobasso skateboards through Santa Ana, trying to find people who need naloxone or testing strips to check drugs for fentanyl. “Narcan?” he asked one man lingering outside a Jack in the Box on a hot day in February. “How many would you like?”

Lobasso explained briefly that he and his co-worker were with a syringe program, even though they had no syringes to offer. “We’re not open right now,” he said. “But we should be. In a few weeks.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.