Column: In charging molester as a minor, Gascón helps critics and hurts reform

- Share via

Somewhere inside the Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in Sylmar, 26-year-old Hannah Tubbs is serving her sentence for sexually assaulting a 10-year-old child in a Denny’s bathroom nearly a decade ago.

The Tubbs case has become fodder for the conservative outrage machine, but in this instance, Tucker Carlson and his far-right gotcha groupies have a point — and I really hate saying that. Though Tubbs was 17 when the crime was committed, it requires mental contortions to see the benefit of treating her as a child now.

The absurdity of prosecuting Tubbs as a minor and the outcome of that decision — likely months in a detention facility for juveniles with little access to sex offender treatment or monitoring after release — are a subversion not just of the legal process, but of years of work that have gone into reforming our criminal justice system. Tubbs has the potential to become an object of fearmongering akin to Willie Horton, the Massachusetts felon who derailed the presidential aspirations of Michael Dukakis in 1988 after George H.W. Bush held the case up as an example of failed second-chance crime policies.

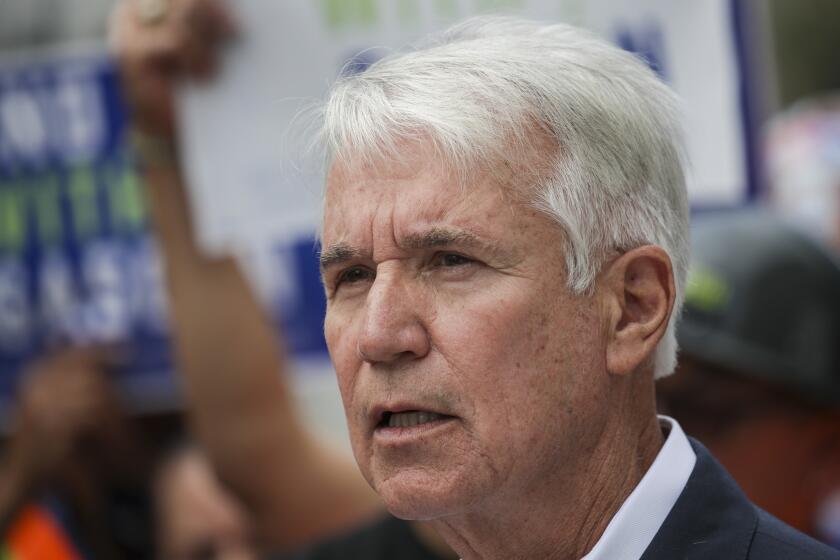

It’s hard to imagine a scenario in which the Tubbs case won’t help the recall effort against Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón. But as we head into an election season in which crime is top of mind for many Californians, Tubbs is a name we will certainly be hearing from political aspirants across the state who oppose what they see as the dangerous, soft-touch approach to offenders that progressives have championed in the last few years.

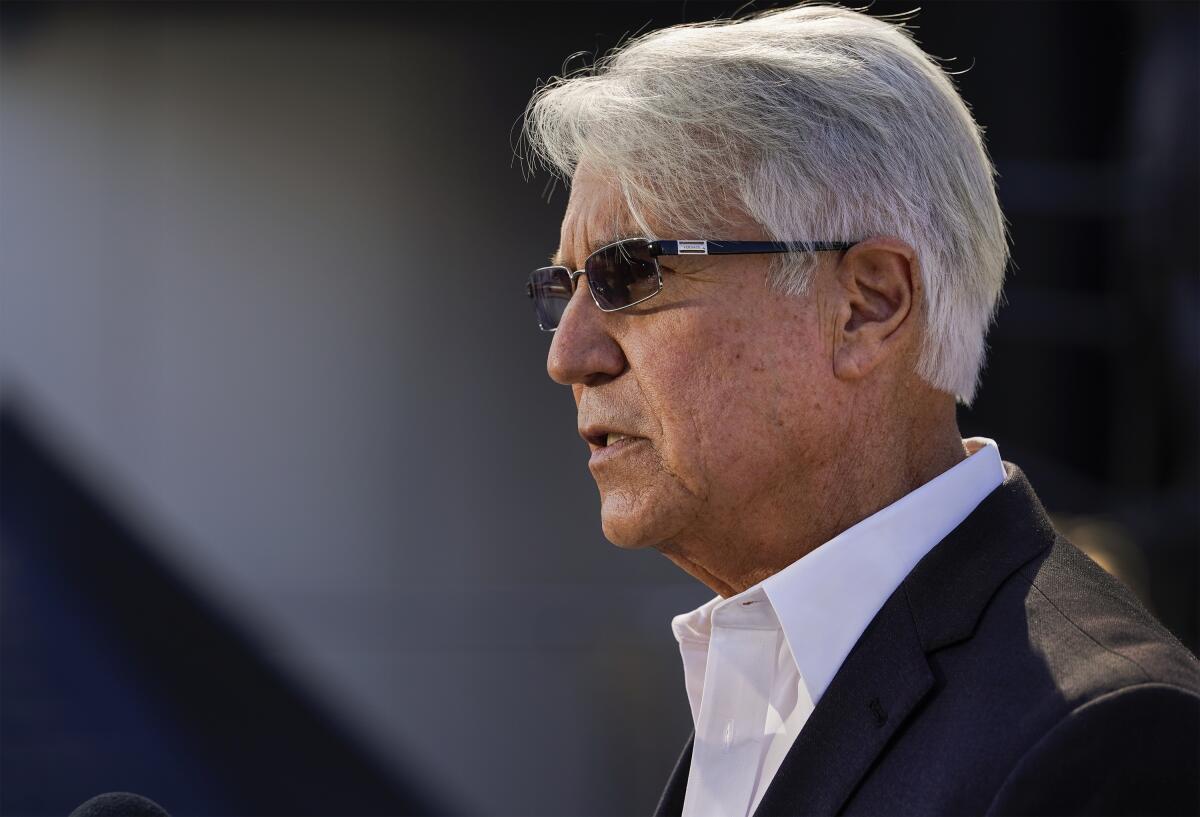

Anne Marie Schubert is Sacramento County’s district attorney and a candidate for state attorney general, running as the old-school foil to progressive Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta. The Tubbs case, she said, “strikes the conscience” and is an example of the “utter failure” of blanket policies like the one (recently changed) in Gascón’s office that prevented juveniles from being tried as adults, no matter the crime or circumstances.

She’s right.

Combine Tubbs with the drug problems in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood (a city with another progressive prosecutor under threat of recall), and California becomes the gift that keeps giving for those who believe we need to dial the clock back to the sledgehammer-justice days that spawned laws like “three strikes.”

The reform-minded prosecutor has made a dramatic shift involving the case of Hannah Tubbs, a 26-year-old tried as a juvenile for assaulting a child.

This is a self-inflicted wound for Gascón, and he needs to truly own it. Otherwise, it could become a referendum on reform. Yes, as my colleagues Harriet Ryan and James Queally have reported in depth, Gascón has changed his ban on prosecuting juveniles as adults and said, “If we knew about [Tubbs’] disregard for the harm she caused we would have handled this case differently.”

But that statement is about shifting blame to his staff. Gascón has been claiming that incendiary jailhouse recordings between Tubbs and her father — in which she appears to mock the lightness of her sentence, as Fox News first reported — weren’t shared with his inner circle early enough in the proceedings. Shea Sanna, the deputy D.A. who tried Tubbs, disputes that, strongly.

The tapes are largely a sideshow, though, except to raise the uncomfortable question about the authenticity of Tubbs’ identity at a moment when transgender people are under attack across the country. I am not speculating on Tubbs’ truthfulness (though Gascón acknowledged the tapes introduce doubts).

The facts of the case, regardless of gender, are enough for even an average person without legal expertise to see Tubbs isn’t a good candidate for juvenile hall.

Tubbs’ interactions with the law go back to at least 2013, when authorities in Kern County were called to a local library after Tubbs — who had not transitioned yet — allegedly exposed herself to a 4-year-old girl. Tubbs was arrested but charges were not filed because the child was not able to provide enough details to detectives, according to court records and a source I spoke with who was not authorized to speak on the record.

The library incident allegedly took place when Tubbs was 17. A few weeks later, on New Year’s Day 2014, about three weeks shy of her 18th birthday, Tubbs committed the assault at Denny’s in Palmdale. In that instance, the victim was having breakfast at the diner when she went to the bathroom on her own. Tubbs came in and forced the little girl into a stall, grabbing her by her neck and putting her hand into the child’s pants to digitally penetrate her. The assault continued until Tubbs thought someone was entering the bathroom and hid in another stall, giving the little girl the opportunity to escape.

After that, it appears Tubbs moved out of state, racking up various convictions in Oregon, Washington and Idaho — none sexual, but some violent, including battery, domestic violence and drug possession. Her rap sheet was described to me as 37 pages long when printed out.

The Denny’s assault was a cold case for a while, but then L.A. investigators were helped in 2019 by a DNA hit from Idaho, where Tubbs was in custody on unrelated charges. Los Angeles sent investigators, but Tubbs was released and the trail went cold.

Tubbs popped up in Kern County again in 2020, where she was tried and convicted of assault with a deadly weapon, accused of repeatedly stabbing a person who declined to give her a ride. She was sentenced to four years in state prison.

When Sanna, the L.A. County assistant district attorney, took over the Denny’s case in 2021, all of that background became known to anyone in the D.A.’s office who cared to review the details. But Gascón stuck with his blanket policy that would require Tubbs to be tried in juvenile court, angering Sanna, who became publicly vocal in his criticism of Gascón.

“I have three kids and a mortgage and a wife, but I am not going to do the wrong thing even if my boss tells to me do it,” he told me, adding that he draws a line when it comes to crimes against little kids. “This case is past that line,” he said.

Sanna’s bitterness isn’t unique in his office. In the wake of the Tubbs case, the line prosecutors union voted overwhelmingly to back a second recall attempt of Gascón just a year into his tenure — with about 545 out of 672 members in favor of ousting him. Faced with that level of dissent in his own ranks, which is not new, it’s easy to understand why Gascón choose to rely on bright-line rules to implement his reforms. It’s simpler. Clear regulations leave little room for maverick decisions.

But Tubbs is a devastating reminder that justice requires nuance. Despite our ideals and wishes, justice has never been blind. It’s plagued by systemic racism, misogyny and often brutality. Those are real problems that have left too many in jail for too long — even with a 20% decrease in the state prison population during the pandemic, Black and brown people remain disproportionately incarcerated.

Traditional crime victims groups are emboldened by the possible recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom and some district attorneys. But other groups are redefining the term ‘victim.’

But making justice deaf and dumb is not the solution. Tubbs’ victim in the Denny’s case didn’t testify at the sentencing, but she did send a statement, one that seems to have been lost in the void. She’s 18 now, and still deeply hurting. She wrote that she thinks of the day of the assault often, and “It makes me sick,” a memory that is like “poison.”

She had rarely gone out for meals, but that day, her brother wanted “to do something good for the family.” Since then, she’s never been able to live life the same way, she wrote, constantly fearful, feeling she was somehow responsible for her own victimization. The attack has made her suicidal, and has put her brother in therapy as well because he felt guilty that he didn’t stop it. Most days, she stays inside because she is afraid of men.

Her hope of the trial was that “after all this comes to an end, my attacker gets the punishment he deserves for attacking a child with no problem and I can finally get on with my life.”

I cannot imagine that Tubbs’ sentence will bring the victim the peace she hoped for. While I know that maybe there was no sentence that would have brought that relief, this outcome feels like another violation. I’m guessing Gascón knows that, and knows he’s responsible for failing to deliver justice on behalf of this teenager.

And though I do not think well of Tubbs, who displayed a disturbing lack of remorse in the jailhouse calls, the sentence does not serve her, either. If progressive reforms are meant to provide healing and help for perpetrators as well as victims, then this sentence is a double failure. Tubbs is not going to receive the deep, meaningful treatment that is essential to prevent future sex offenses. Even if she serves her whole two-year term, which would be unusual, she will probably remain in a facility with little expertise in helping people like herself.

Beyond the mess of this case, it’s now on Gascón to figure out how to keep Hannah Tubbs from being synonymous with a failure of the progressive re-imagining of the justice system that brought him into office. The only way to do that is to own Tubbs as a personal defeat — the result of a lack of attention to the details of Tubbs’ past, a genuine management problem in his ranks, and an acknowledgment that, as his critics have long claimed, blanket policies don’t work — even when they’re well-intentioned.

Heavy is the head, as they say. But Hannah Tubbs’ victim will never receive the justice she deserves, and can be left with only more mistrust.

She should at least receive an apology, and the rest of us an assurance that this isn’t where Gascón meant to take us when L.A. County voters elected him to fix the system.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.