Omicron landed in affluent L.A. But poor communities of color ended up being hit hardest

- Share via

The Omicron wave swept through Los Angeles over the last two months with unprecedented speed, but ultimately traced a grim path that is becoming increasingly familiar two years into the pandemic.

Cases first exploded in affluent communities, where air travel likely introduced the latest coronavirus variant, which got a head start in places like South Africa, London and New York.

At first, it appeared the variant might be a “great unifier,” spreading equally throughout the county, but then it took a hard turn toward lower-income communities of color that had already suffered the most throughout the pandemic.

By January’s end, officials with the L.A. County Department of Public Health said South and South Central Los Angeles, East L.A. and parts of the San Fernando Valley once again had the highest coronavirus case rates in the county.

The shifts “likely reflect the fact that we’re now seeing increased transmission among those whose jobs are putting them in close contact with others and who often live in crowded housing,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said.

The findings lay bare how even a highly contagious variant like Omicron couldn’t overcome the pervasive and systemic inequities of public health in a massive county like Los Angeles.

Though Omicron is proving to be generally milder than earlier strains of the coronavirus, essential workers, people who live in dense or multigenerational housing and those with underlying health issues remain the most at risk.

“We haven’t, in two years, really changed any of those things that led to COVID impacting those communities or those regions more throughout this entire pandemic,” said Joanne Preece, director of government and external affairs at the Community Clinic Assn. of Los Angeles County. “Those same structural issues remain.”

Indeed, nearly every stage of the pandemic has been marked by inequities. The first phase saw the coronavirus sweep through Black and Latino communities at a rapid clip, while the initial rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine in 2021 disproportionately favored white people, young people, residents with money and those with access to transportation, among other groups.

Even today, nearly two years into the pandemic and a year into vaccine distribution, only about 52% of Black and Latino people in Los Angeles County are fully vaccinated, compared to 70% of white people and 82% of Asian residents and Pacific Islanders, according to the Times tracker.

Though county officials have worked to overcome disparities through community-driven efforts, such as door-knocking and mobile clinics, many barriers remain, and the virus continues to take the highest toll on L.A.’s most vulnerable residents.

And while those with greater access to vaccines, transportation or work-from-home options are not immune to Omicron, their outcomes continue to be much better.

At the South Central Family Health Center, development director David Roman said it’s not at all surprising that case rates are highest in his community. Many of the health center’s patients are essential workers who “never had a choice about stopping work or not being in public,” he said, and many still can’t get time off to get vaccinated or recover from illness.

“We have people who work in this informal economy who are most vulnerable,” he said. “They don’t get time off, and not only that, they don’t get paid time off. So if they don’t work, their families don’t eat.”

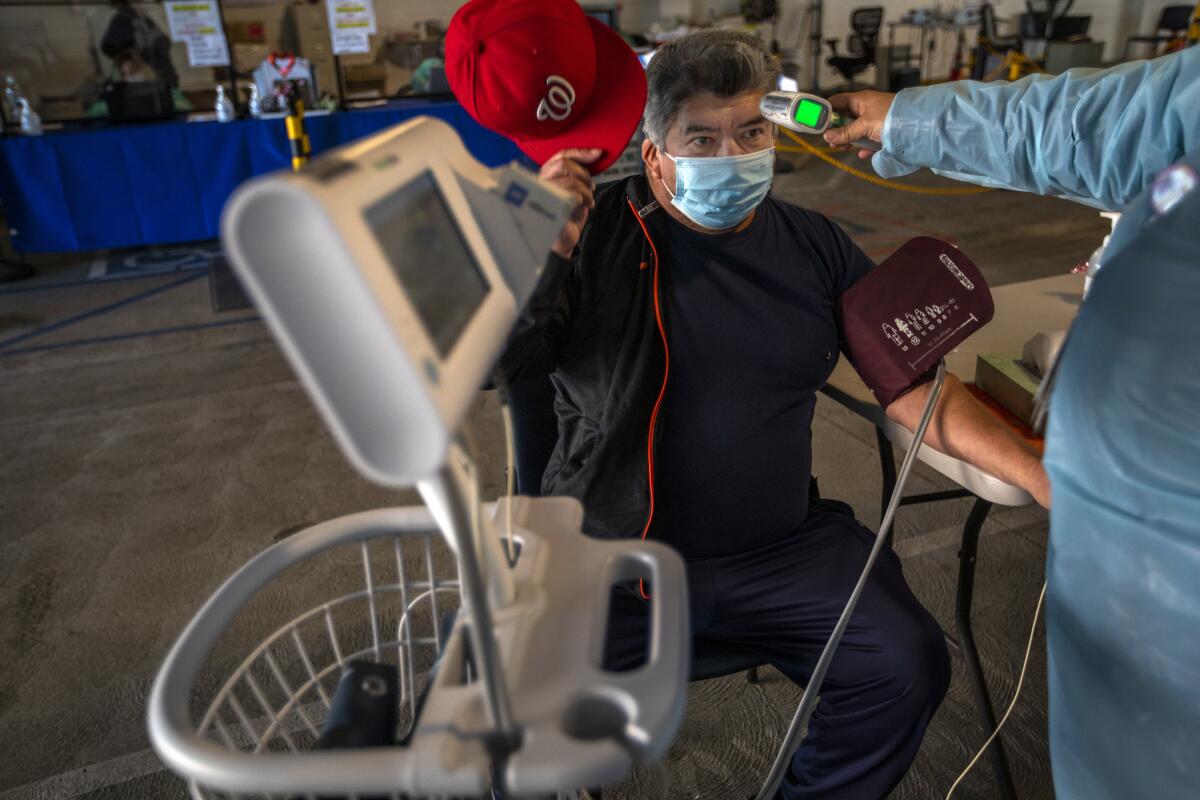

At the clinic, patients queued up in a covered parking lot that had been converted into a testing and vaccination site. Many people were seeking services early in the morning before work.

California has reported more than 8 million coronavirus cases since the pandemic began, or 1 out of every 5 residents testing positive at some point.

One patient, 21-year-old Ana Ortiz, said that between her two toddlers and her job at Wingstop, she had trouble finding time to get the vaccine. She was at the clinic awaiting her second dose of Moderna while her 3-year-old, Adrian, wriggled in her lap.

But there are other factors beyond time that are keeping the community sick, Roman said, including housing density and multigenerational living that can easily translate to six or eight people under one roof where the virus can easily spread.

Even the new federal program to provide COVID-19 tests to Americans is limited to four tests per household, which “doesn’t meet the unique needs in our community,” he said.

What’s more, many in the community have secondary or underlying health conditions — such as diabetes, obesity and hypertension — that make them more susceptible to the coronavirus, in large part due to a lifelong and systemic lack of access to healthcare. Roman called it “the trickle-down economics of healthcare.”

No medical procedure more visibly demonstrates how COVID-19 became especially deadly in these neighborhoods than diabetic amputation.

Many patients waiting at the South Central clinic described the pandemic’s toll on their families, livelihoods and community.

Blandy Amaya, 41, is a vendor who sells hot dogs outside large stadium events. She said the cancellation of events because of the virus hit her hard economically, and there are still many months without steady work.

She was grateful for free school lunches, which helped keep her youngest children fed during the pandemic, she said as she waited to get her first dose of the vaccine — a decision she ultimately made for their protection.

Another patient, Jose Gasca, said he’s been out of work for eight months because he worked in the restaurant industry. He said tonier neighborhoods like Hollywood, where he worked in the past, seemed more strict in their response to the pandemic and more in control.

“The experience has been better over there than over here,” he said.

Gasca, 59, was waiting to get his booster shot but said he was still concerned about the lack of clear information being given to his community about the vaccines and the Omicron variant, noting that “it would be better if we knew more.”

One factor that has made the Omicron surge more challenging than earlier stages of the pandemic is healthcare staffing shortages tied to the highly transmissible variant. The problem has been nearly universal in California, but it has created a particular crunch for clinics that staff from within communities that are already sick.

“We are part of the community,” said Ilan Shapiro, medical director of health education and wellness at AltaMed Health Services, a community health group headquartered in East Los Angeles. “Most of our nurses and doctors and everybody else, we live in and are part of our community, and we are still exposed to everything that’s happening now.”

Like South Central, East L.A. has been hit hard by the Omicron wave. The area reported nearly 5,800 new cases in the last two weeks, among the highest in the county.

But misinformation, miscommunication and confusion have compounded the crisis, Shapiro said, noting “that it’s painful watching people get sick because they thought that vaccines didn’t work, for whatever reason.” His team is working to reach more community members and help them get immunized and boosted, among other efforts.

And while earlier surges of the pandemic felt like “a horror movie,” Shapiro said, the Omicron surge was more akin to a drama because so little has changed.

“The drama is that we know right now what to do. It’s not the first year, when we didn’t have any idea, we didn’t have vaccines, we didn’t have medications, we didn’t have technology. ... Right now, after two years, we know what works,” he said.

Some things are indeed making a difference, including plans to expand sick pay and improve the Medi-Cal system, said Preece, of the Community Clinic Assn. There are also some signs that the Omicron surge is beginning to wane, and the general mildness of the variant means fewer patients are becoming severely ill.

Those factors, along with countywide efforts to reach more people through mobile clinics, information campaigns and improved accessibility are helping move the needle.

“There’s small glimmers, small rays of light, if you will. I hope that the desire is there and that we remain committed to it,” she said.

There remains considerable debate about the pandemic’s trajectory, but scientists generally say it’s too early to declare an ‘endgame’ for COVID-19.

But while some sectors are already focusing on an equitable recovery from the pandemic, many of the communities the clinic association serves are still focused on an equitable response.

“I hope that we really continue to carry this conversation forward when — if — we get to recovery, and really think about the structural issues that led to those disparities in the first place,” she said.

Building up the healthcare infrastructure in those communities, along with investing in staffing and safety net services, are urgent and necessary goals, Preece said, as is getting more vaccines into arms.

But there is also a difference between managing the short-term surge and responding to the long-term crisis that lead to communities like South Central and East L.A. bearing the brunt of the pandemic in the first place, she noted.

“Overcrowded housing, high cost of living? These are really tough nuts to crack,” she said. “It’s going to take a really long time, and I hope we don’t forget the lessons we’re learning through this pandemic.”

Times staff writer Sean Greene contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.