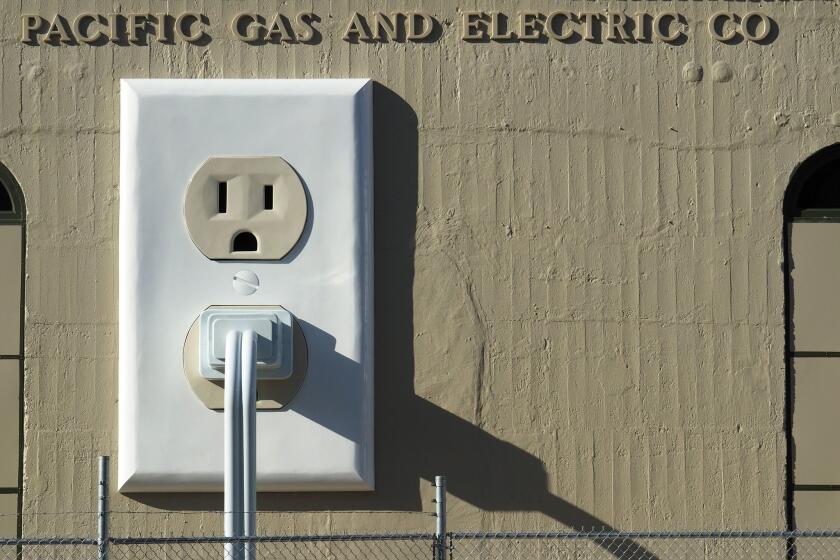

PG&E power line sparked the nearly million-acre Dixie fire, investigation finds

- Share via

State investigators have determined that a Pacific Gas & Electric Co. power line was responsible for sparking last year’s massive Dixie fire, which torched more than 960,000 acres in five Northern California counties as it burned clear across the Sierra Nevada.

According to a statement by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, investigators found that the fire “was caused by a tree contacting electrical distribution lines owned and operated by Pacific Gas & Electric located west of Cresta Dam.”

The department’s investigative report was forwarded to the Butte County district attorney’s office, according to Tuesday’s statement.

Cal Fire officials referred all questions regarding the report to prosecutors. The district attorney’s office could not be reached for comment Tuesday night.

PG&E said in a statement Tuesday night that “a large tree struck one of our normally operating lines,” noting that it had discussed the incident in a July news briefing and that the tree was one of 8 million within striking distance of its lines.

The utility said it has committed to burying 10,000 miles of lines in addition to the risk reduction efforts included in its 2021 Wildfire Mitigation Plan.

“Regardless of today’s finding, we will continue to be tenacious in our efforts to stop fire ignitions from our equipment and to ensure that everyone and everything is always safe,” the statement said.

The Dixie fire is not the first wildfire state investigators have traced to the utility company’s equipment. In December, PG&E agreed to pay $125 million in fines and penalties under a settlement reached with state regulators after Cal Fire found that a faulty transmission line sparked the Kincade fire, which tore through more than 77,000 acres of Northern California wine country in 2019.

Earlier last year, PG&E emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy, with former Chief Executive Bill Johnson promising it would be “reimagined” after wildfires ignited by the utility’s equipment in 2017 and 2018 killed more than 100 people. The vast majority were killed in the Camp fire, which destroyed the town of Paradise.

PG&E filed for bankruptcy protection in January 2019 to shield itself from tens of billions of dollars in potential liabilities due to its role in the fires. The company pleaded guilty last year to 84 counts of involuntary manslaughter in connection with the Camp fire and agreed to pay the maximum criminal fine of $3.5 million plus $500,000 for the cost of the investigation.

As Pacific Gas & Electric exits bankruptcy, it’s not clear there’s anything fundamentally different about the California utility.

The Dixie fire, which started July 13, 2021, burned 963,309 acres and destroyed more than 1,400 structures, Cal Fire said. By the time it was contained Oct. 25, it had become the second-largest fire on record in California, surpassed only by the 2020 August Complex, which scorched 1,032,648 acres in Northern California, the state fire agency said.

In August of last year, the Dixie fire roared through Greenville, a Gold Rush town of about 1,200 people. The inferno reduced a large swath of the town to rubble and ash.

The destruction by the Dixie fire of a large swath of the Gold Rush town of Greenville left residents stunned and mourning all that has been lost.

The fire grew large and intense enough to produce its own lighting and, along with the Caldor fire that tore through the Lake Tahoe Basin, became the first fire to burn from one side of the Sierra to the other in what authorities called an unprecedented fire season.

Officials pointed to several factors that helped 2021’s fires intensify rapidly. Some burned in areas with terrain challenging enough to hamper firefighting efforts from the ground. High winds acted as bellows, causing the fires to spread through the unusually dry trees and grass with shocking speed.

Experts say there is a lot to learn from the state’s second-largest fire, including how it spread — and how firefighters stopped it.

Challenging conditions persisted for weeks until firefighters caught a break with the weather. Rain and slower winds allowed crews to get ahead of the flaming fronts, and when the Dixie fire reached less steep terrain, firefighters were able to attack with bulldozers and hoses, officials said. Previous prescribed burns in some areas also helped by starving the blaze of fuel.

By December, a series of powerful storms dumped record-breaking amounts of snow and rain over California, replenishing reservoirs and raising the snowpack to 160% of its average for that time of year.

But officials warn that the danger isn’t over. After two of California’s driest years on record, more snow and rain will be needed to break the drought.

Storms in December pushed California snowpack to 160% of average, giving a boost to the state’s drought-depleted water supplies.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.