San Francisco confronts a crime wave unusual among U.S. cities

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — It’s the sentimental things people are desperate to recover: a child’s notebook, a wooden cross, an Army backpack that survived two tours in Iraq.

These are among the possessions Mark Dietrich has retrieved from curbsides here in recent months, hastily dumped evidence of the smash-and-grab burglaries and petty thefts that have become a feature of everyday life in the city.

Dietrich is among an increasingly loud group of local activists who say such crime has spun out of control in San Francisco.

“We have all asked ourselves, is it time to go?” he said. “Lots of people have just said, ‘I’m not putting up with this mess.’”

Unlike nearly every other big U.S. city, San Francisco did not see a significant uptick in homicides during the pandemic. Instead, it has found itself in the grip of a different sort of crime wave.

With security cameras everywhere, social media have exploded with videos of young men brazenly stuffing their backpacks with everything from beer to Tylenol or using drills to crack open people’s garage doors. That has fed the impression that the city has become a lawless place and left residents bitterly divided over the roots of the problem and how to solve it.

Crime rates in Dietrich’s neighborhood, a foggy stretch of northwestern San Francisco known as the Richmond district, have traditionally been some of the lowest in the city.

But in the disordered wake of the pandemic, a growing sense of unease has pervaded the neighborhood as homeless encampments appeared and burglaries and other street crimes shot up.

Dietrich started to see people shoplifting every time he went into the Walgreens or Ross a few blocks from his house, and when he mentioned it to the security guards, they shrugged helplessly.

“Then one day I found a bunch of needles on the sidewalk where my kid plays,” he said.

The 51-year-old retail analyst has since positioned himself as an anti-crime crusader defending his neighborhood. He said he’s only doing what the city’s progressive leaders have failed to do. His activities have ranged from organizing trash cleanups to showing up at crime scenes on his bicycle.

“People are calling me, and neighbors are emailing me, so I’m gonna help them,” he said.

::

Unlike in Oakland, right across the bay, which is facing a sharp increase, homicides in San Francisco jumped only slightly, from 41 in 2019 to 48 in 2020 — one of the lowest rates on record.

Burglaries, break-ins and shoplifting are much harder to measure, because people don’t always report them.

San Francisco has long registered a consistently high rate of property crimes, and in 2019, the city had the highest rate of larcenies, burglaries, arsons and car thefts in California, according to an analysis by the Public Policy Institute of California.

Industry groups and politicians are sounding alarms over the thefts. But in some cases, the statistics they cite are inflated or flat-out wrong.

As the pandemic emptied the streets of tourists and commuters, the city’s most notorious crime — auto break-ins — plunged.

But burglaries climbed nearly 50% in 2020 and remained up in 2021. Car thefts have also soared.

People who commit property crimes run the gamut from addicts stealing for drug money to organized syndicates who fence goods on the internet.

San Francisco’s high property crime rate probably reflects the widening wealth gap that accompanied the tech boom, which flooded the city with jobs and money and drove up the cost of housing, said Magnus Lofstrom, a criminal justice researcher for the Public Policy Institute.

The city has one of the highest levels of inequality in the state. Expensive townhouses containing $10,000 bicycles sit blocks away from homeless encampments.

“You have very wealthy individuals, and at the same time you have a number of individuals who are struggling. … There are parts of San Francisco where poverty is a real issue,” Lofstrom said.

Authorities speculate that during the pandemic, the suddenly empty streets and padlocked businesses became easy targets for thieves who no longer had gullible tourists to prey on.

The vast majority of the burglaries are never solved, and victims of nonviolent crimes often end up waiting hours for the police, especially since the department is down nearly 500 officers, as many have taken jobs in more cop-friendly communities with cheaper housing.

A poll conducted in June by the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce reported that 80% of residents believe crime is getting worse.

Among them is San Francisco native Max Young.

He had grown accustomed to lawlessness in the Tenderloin neighborhood, home to the city’s infamous open-air narcotics mart, blocks from City Hall and Twitter’s headquarters. He owned a nearby bar, Mr. Smith’s, but shut it down in 2019 due to rampant drug dealing.

He never imagined the chaos would spread to the Richmond, where he grew up and still lives with his wife and two daughters.

“San Francisco used to be the safest place,” he said. “Is it different now? Absolutely.”

::

For much of the city’s early history, the Richmond was part of the Outside Lands, a windswept expanse of sand dunes where San Franciscans buried their dead. Even today, from the Asian eateries of Clement Street to the Russian churches and cotton-candy-colored homes that slope toward the Pacific, this neighborhood has retained an identity distinct from the flashier parts of the city.

The tranquility was shattered when burglaries there shot up 87% in 2020 and another 6% in the first 11 months of 2021.

In late October, someone broke into Seakor Polish Deli, where Jerry Sikora’s family has been selling sausages for 44 years.

Sikora, who wears a red apron and chats in Polish with his regulars as he wraps kielbasa and smoked herring in white paper, said he arrived at the store one morning to find shattered glass. It was the first time the deli had been burglarized.

He was careful not to touch the small black rock he found on the floor, which the intruders had apparently used to break in.

“I thought maybe they could take some fingerprints or something,” he said. “But when I mentioned it, the cops just started laughing.”

A few blocks down Geary Boulevard at Joe’s Ice Cream, no item has proved too small to steal. Thieves have repeatedly pilfered the tip jar. Owner Alice Kim says she’s even been forced to move the fresh bananas she used to keep near the counter for banana splits.

Kim said: “Anything you can reach disappears.”

On Clement Street, a normally bustling strip of ethnic markets and hole-in-the-wall dim sum joints where people line up outside at mealtimes, there was a period in early 2021 when every night, at least two or three businesses got hit, said business owner Amanda Michael.

She said struggling mom-and-pop shops could not afford to hire armed security guards or install expensive alarm systems.

“Around here, we’re all small merchants who don’t have $18,000 to pay for high-tech security gates,” said Michael, who owns Toy Boat by Jane, a beloved dessert cafe and neighborhood fixture of nearly 40 years.

She bought the cafe last year after reading that it was about to go out of business and recalling how she used to eat ice cream there as a teenager.

Michael aimed to preserve the shop’s old-fashioned ambiance, with its black-and-white checkerboard tiles and vintage toys decorating the perimeter.

Then the place was hit by three burglaries — including one in which someone used a BB gun to break a window — as well as a couple of vandalism incidents.

The burglars took the toys, including Godzilla dolls and vintage tin robots that Michael guessed might fetch $40 on eBay. Afterward, neighbors stepped up to donate replacement toys — only to have them stolen again.

“I get that people are angry,” Michael said. “But they’re going after these mom-and-pop business owners who are really doing all they can to stay afloat.”

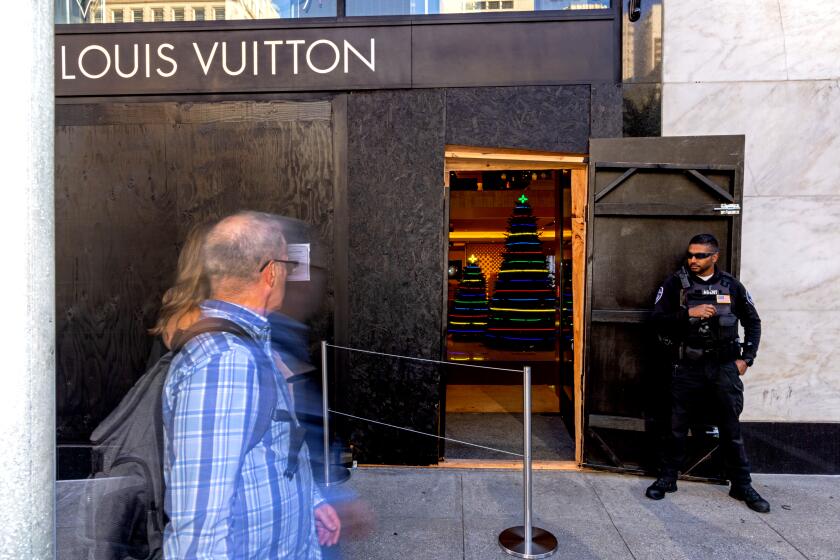

It’s not just small businesses that say they are being victimized.

A few days before Thanksgiving, Walgreens closed its store at 745 Clement St., spurring widespread lament among local seniors and poor families who had shopped there. The company blamed the closure — and 21 others in the city in the last few years — on rampant shoplifting, which it said happens in San Francisco at four times the chain’s national average rate.

Some have cast doubt on whether crime was the real reason behind the closures, which were among hundreds the $140-billion retailer has initiated amid competition from e-commerce and pandemic-related losses.

But some San Franciscans feel no doubt about who is to blame. A couple of days after the closure, someone hung a banner across the front of the locked glass doors bearing the smiling photos of the city’s district attorney, Chesa Boudin, and the local District 1 supervisor, Connie Chan.

Both are progressives whose permissive policies have been blamed — fairly or not — for emboldening street criminals and feeding a general sense of chaos in the city.

Boudin, a former public defender elected in 2019 promising long-overdue criminal justice reform, now faces a June recall election.

::

Dietrich, who calls himself a “lifelong liberal,” is among the critics.

He figured crime would subside as the pandemic calmed. But as tourists trickled back to the city last spring, San Franciscans once again started seeing the telltale shards of rental car glass glittering on the sidewalks.

That was when Dietrich began finding opened luggage littered around his home on 16th Avenue, apparently a convenient spot on the car-burglar getaway route.

Security camera footage showed several men hastily pulling up in a dark gray sedan one day in May just long enough to dump flip-flops, T-shirts, toiletries and other rifled possessions on a curb.

With some basic detective work and help from social media, Dietrich was able to return most of the stolen items to grateful tourists — of course, minus the laptops, iPads and cash.

It’s made Dietrich a local hero to some, and lately people have been asking if he plans to run for office. He said he’d prefer to stay out of politics — but that he feels obligated to be a good neighbor.

But he and other residents who post frequently about crime on social media have also generated their own critics.

Julie Pitta, a longtime resident of the neighborhood, acknowledged the surge in burglaries but maintained that Dietrich and his allies are stoking hysteria.

“Nextdoor reads like a crime blotter,” she said. “You hear the same people ranting about the same things. They say: ‘I’ve lived here for 30 years, and it’s never been this bad.’”

Pitta’s husband grew up in San Francisco in the violent 1970s, when the city’s homicide rate was nearly triple its current level. He ridiculed the idea that crime was out of control, telling her: “It was awful back then. My parents’ house got broken into three times.”

Richard Correia, a native of the Richmond district and retired police commander who once oversaw the neighborhood, said he understands why people may be terrified by scenes of homelessness and addiction on the streets. But he said he believes the neighborhood remains relatively safe.

“I think it’s irresponsible to, day after day, post pictures of broken car windows and say, ‘Look! We’re going to hell in a handbasket,’” he said.

The COVID-19 pandemic — which has kept many businesses closed and many people at home — is definitely a major factor, though analysts say the full answer is likely more complex.

On the other hand, some of the photos of stolen items have helped Dietrich and a few other neighbors reunite break-in victims with their discarded luggage.

The beneficiaries include a real estate agent from Florida, a Japanese exchange student and a girls’ college volleyball team from Pasadena whose parked van was raided by burglars.

Clifton Roth, a former pastor from Kentucky, visited San Francisco recently with his wife and two other couples after touring wine country. They stopped at Lands End Lookout to take in the breathtaking views of the Golden Gate Bridge and the Marin Headlands, but when he returned to his rental car, he found the windows broken and their luggage gone.

He was waiting for the rental car company to send a tow truck when two men pulled up in an SUV, and one of them stepped out and began peering in car windows with a rock in his hand.

Roth and his brother-in-law shouted at the men, who sped away. A few hours later, his group managed to get back most of its things, with the help of Dietrich and other residents.

“This is one of the most beautiful cities I’ve been to,” Roth said. “But if I came back, I think I’d be looking over my shoulder.”

Scheier is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.