In 2021, the recall circus returned to California. Republicans sent in the clowns

- Share via

By March, Gov. Gavin Newsom knew he was in trouble.

His people had been tracking what, until then, was a mostly nascent campaign to recall the Democrat from office. It’s the sort of thing generations of California governors have faced, and only one — Gov. Gray Davis — with real political consequences.

But, this year, the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything.

“In 25 months, there’s been six efforts to put a recall on the ballot,” Newsom said in mid-March on ABC’s “The View.” “This one appears to have the requisite signatures,” he acknowledged.

Indeed, by April, Secretary of State Shirley Weber declared that enough signatures had been verified — more than 1,495,709 — to force a recall election by the end of the year.

From the Capitol riot to vaccines and climate change, a look at what dominated the news and conversation in 2021 as the world began to move past the pandemic.

That campaign Newsom once dismissed as the purview of the far right — alongside Trumpism, anti-vax conspiracy theories and a refusal to wear face masks? It had suddenly gained mainstream appeal.

All it took was the governor secretly violating his own public health orders on COVID-19, going out to dinner with friends and doing so at a Michelin-starred restaurant that most Californians navigating a pandemic-crunched economy could never afford.

“I want to apologize to you because I need to preach and practice, not just preach and not practice, and I’ve done my best to do that,” Newsom said after being caught. “We’re all human. We all fall short sometimes.”

“COVID fatigue,” he added, “is exhausting.”

Right.

By May, the recall circus was well underway. As was the case in 2003, when a deeply unpopular Davis was fighting for political life, dozens of unqualified clowns signed up to be candidates.

Among the most prominent: the millennial YouTuber Kevin Paffrath, the obnoxious Olympian-turned-reality-TV-star Caitlyn Jenner and the failed gubernatorial hopeful John Cox, who crisscrossed the state with a 1,000-pound Kodiak bear named Tag.

“We’re gonna need big, beastly changes to be made in this state,” Cox said during a campaign stop in Sacramento, while Tag snacked on cookies and chicken. “We’re going to have to be tough as a beast to go against the special interest groups.”

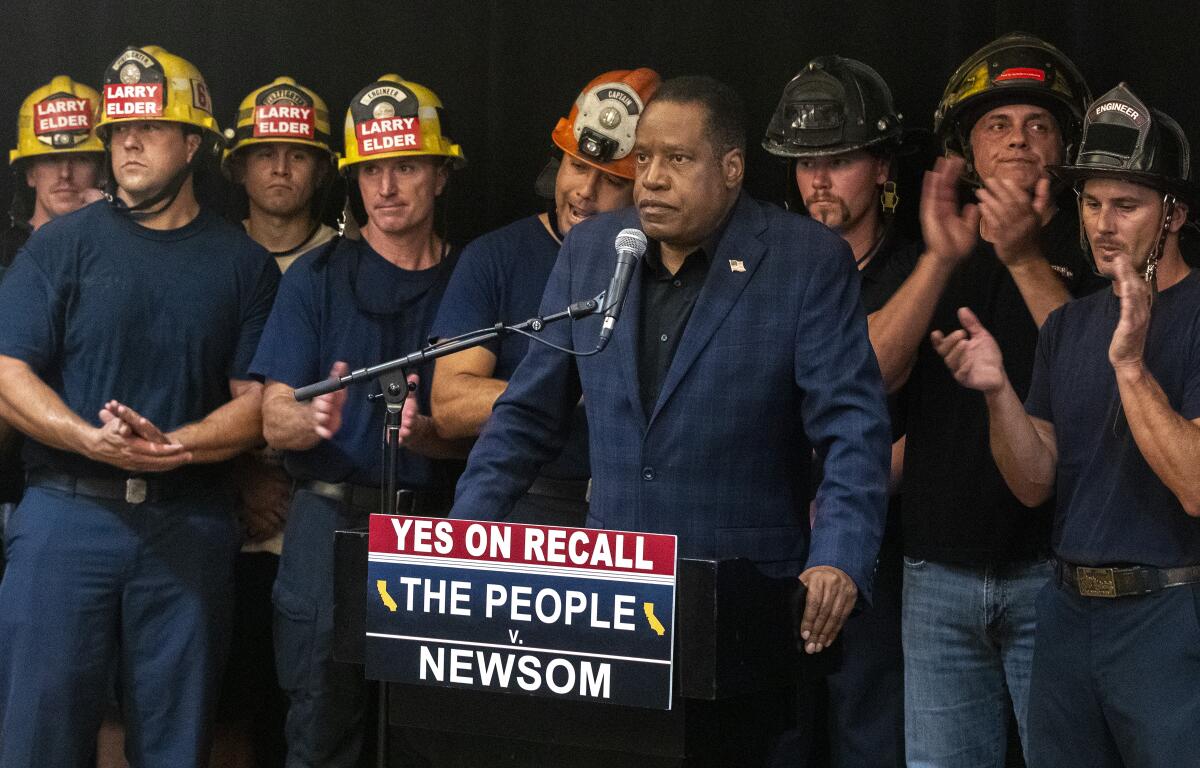

The biggest entrance to the race came in July. That’s when Larry Elder, the loudmouth radio talk show host known for mentoring Trump sycophants and demonizing Black liberals to entertain white conservatives, decided he was going to “save” the state.

As the self-proclaimed “Sage of South Central,” Elder had name recognition and no experience. That, of course, set him up for a rapid rise to the top of the polls, above more traditional candidates such as former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer and Assembly member Kevin Kiley.

Elder vowed to do away with mask and vaccine mandates, put the brakes on police reform and, for all intents and purposes, ignore climate change and systemic racism. He also said some dumb stuff about homelessness, which no doubt prompted the egging he received while trying to tour a Venice encampment in a three-piece suit.

As President Biden said of Elder while stumping for Newsom in Long Beach, “The leading Republican running for governor is the closest thing to a Trump clone that I have ever seen.”

Despite all of this, by the final weeks of the race, Elder had an actual shot at being governor. Blame California’s nonsensical recall election process.

Lucky for Newsom, in this bluest of blue states, where the vast majority of the electorate is terrified of electing anyone at all connected to former President Trump, the governor managed to handily beat back the recall attempt.

As he said in his no-frills victory speech: “Democracy is not a football. You don’t throw it around.”

As 2021 comes to a close, I find myself wondering what — if anything — California learned from this embarrassingly expensive exercise in ego-stroking political theater. And what — if anything — will come of it.

At the very least, we seem to have learned that the recall process needs an overhaul.

“Californians are very frustrated that we just spent $276 million on this recall election that, from the looks of it, certified what voters said three years ago,” Assembly member Marc Berman of Menlo Park said in September.

Hearings are already being held by the election committees of the Legislature.

But I suspect the impact of the recall election won’t stop there. Rather, it will be felt most across the nation.

Consider that after Newsom trounced his would-be Republican ousters, political watchers speculated that his strategy of tying Republican candidates to Trump was one that would help Democrats in the midterm election.

Fast-forward a few weeks. Democrat Terry McAuliffe tried the “Trump clone” strategy while running again for governor of Virginia, an office he left in 2018 — and Republican Glenn Youngkin won anyway. Now those political watchers aren’t so sure anymore.

Just as important, Winsome Sears won the race for lieutenant governor, becoming the first Black woman elected to statewide office in Virginia’s history.

A conservative Republican, she previously led the national committee to boost Black voter turnout for Trump. She rails against critical race theory, insists that voters are being pitted against each other based on race and argues that Black people are coddled too much by government programs.

Sound familiar? Call it the Larry Elder strategy, pioneered right here in California. What better way for Republicans to avoid talking about their party’s embrace of white supremacists than to promote Black conservatives?

Former NFL player Herschel Walker is trying the same trick in Georgia with a run for the U.S. Senate. Trump might try it too, as he weighs options for a running mate in 2024, Trump’s pollster speculated to Politico.

The night Elder lost his bid to replace Newsom, he promised his mostly white, Republican supporters that he’d be back.

“We may have lost the battle,” he said, pacing a stage in Costa Mesa, “but we are going to win the war.”

Not in California. But the rest of the country could be in trouble.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.