Column: This priest died of COVID-19. His congregants got vaccinated in his honor

- Share via

MECCA, Calif. — There are no public memorials for Father Francisco Valdovinos, a beloved Catholic priest in this unincorporated Coachella Valley town who died of COVID-19 at 58.

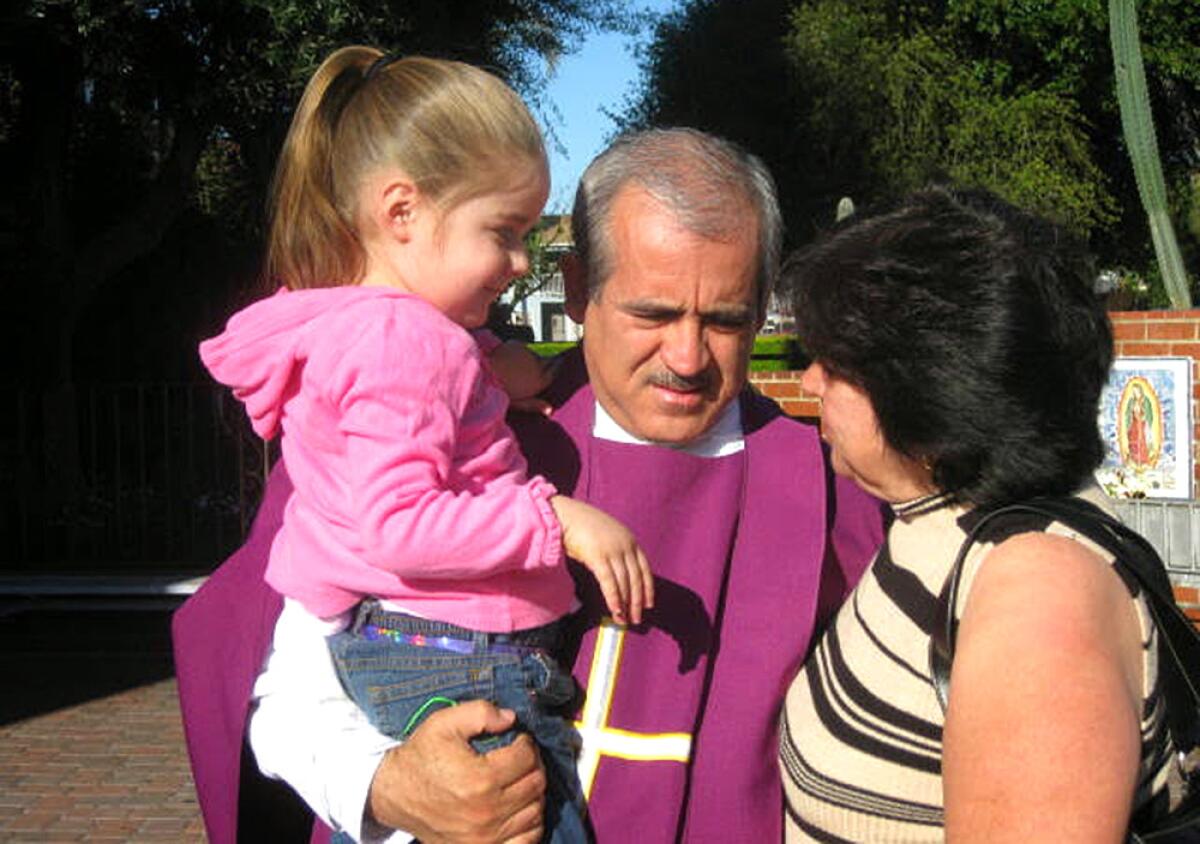

The member of the Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity arrived in 2018 to serve at the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Guadalupe and immediately endeared himself to locals. The balding, burly, mustachioed Mexican immigrant pressed politicians to bring better services for his working-class congregation, and brought in literacy and legal classes on his own.

His homespun sermons packed the church every weekend, and the priest frequently visited the region’s agricultural fields with lunches for campesinos, many of whom hailed from his native Michoacán.

When the pandemic tore through the eastern Coachella Valley last year, Valdovinos transformed his picturesque parish into a food distribution center and testing site. He gave out masks by the tens of thousands and offered socially distanced Mass, while appearing on Spanish-language radio to urge listeners to take the pandemic seriously and to get the vaccine once it was available.

When word emerged in December that COVID-19 had struck Valdovinos, parishioners held vigils outside the hospital where he was dying. More than a thousand people prayed during a Facebook Live session. A January caravan to honor his life snaked around Mecca, with cars and trucks bearing messages in Spanish such as “Thank You for Everything” and “We Miss You.”

“The community cried when he died,” said Conchita Pozar, 32, a leader in the Coachella Valley’s sizable Purépecha Indigenous community. “He went above and beyond what most priests ever do. He could’ve just given Communion at Mass and that would’ve been fine. But he pushed everyone to do more. His legacy is now in our hearts.”

There are no public memorials in Mecca for Father Francisco Valdovinos. There’s no need for any. Proof of Mecca’s gratitude toward him was everywhere when I visited last week.

Hand sanitizers sat on a table in Our Lady of Guadalupe’s foyer, and near the sacristy. Red and blue stickers spaced six feet apart marked sidewalks and pews. Signs around the church campus in English and Spanish and affixed with a sticker of la virgencita urged everyone to wear masks. In town, everyone seemed to be wearing them, whether women at an evening Zumba class in one of Mecca’s few strip malls, men hanging out in what passes for the town’s downtown, or kids playing baseball underneath the lights at the sports complex.

The most lasting tribute to Valdovinos wasn’t readily visible, though: Mecca’s COVID-19 vaccination rate. News accounts in the wake of his death quoted residents who vowed to roll up their sleeves in his honor. And they did.

According to figures by Riverside County Public Health, 108.4% of Mecca residents are fully vaccinated — a statistical impossibility explained by the fact many Coachella Valley residents got their shots in the town. California Department of Public Health records are more accurate — the most recent data show 93% of residents in the 92254 ZIP Code that encompasses Mecca and the smaller communities of North Shore and Desert Camp are fully vaccinated.

It’s just one of two ZIP Codes to hit that mark in the Inland Empire, where only 53.4% of residents are fully vaccinated, and barely half in San Bernardino County. And Mecca is part of an exclusive California coronavirus club: Only 4% of the state’s 1,741 ZIP Codes have achieved 90% full vaccination.

“When Father Valdovinos died, he awakened the consciousness of the people in our community to go out there and get the shot,” said Assemblymember Eduardo Garcia (D-Coachella), who represents the region and honored his sacrifice on the state Capitol floor shortly after his passing by adjourning a meeting in his name. “For their health, yes, but also out of respect for his life.”

“He was just building momentum,” said Maria Machuca, a former school trustee and longtime community organizer. “It’s just a big loss — we don’t know what he could’ve done. So we need to continue what he did.”

Valdovinos was born in 1962 in the pueblo of Santa Ana Amitlán to a family of lime farmers. He studied to be an electrician as a young man. Then one year, members of the Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity (also known as Trinity Missions), a Catholic men’s congregation devoted to poor and marginalized communities, came to his hometown.

“He saw the good that we did, and decided to join us,” said the Rev. Guy Wilson, S.T. He’s a pastor at Sacred Heart Church in Camden, Miss., vicar of missions for Trinity Missions, and was part of the delegation that inspired Valdovinos to become a priest. “He was determined even then to help.”

Valdovinos was ordained in 1994, and ministered in Puerto Rico and Costa Rica before finding his social justice groove in Tallahassee, where he’d drive more than 300 miles on weekends to visit labor camps and prisons across northern Florida. He moved on to Our Lady of Victory Church in Compton in 2007, where Valdovinos decided to combat violence in the city with adult education classes, health fairs and youth counseling.

“How can you stop violence with no job, no education, no food, no housing, no transportation?” he told the L.A. Daily News in 2015. “This is a culture of violence, from generation to generation, in which they’re accustomed to live that way.”

Three years later, Trinity Missions asked Valdovinos to head Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mecca. Wilson was pastor of Our Lady of Soledad Church in Coachella at the time, and remembered the initial hesitation Valdovinos felt.

“He never wanted to leave any mission he worked at,” Wilson said. “When Francisco saw something needed to be done, he put his energies to it, and you weren’t going to take him away from him. But in Mecca, Francisco really found his home.”

At his first Mass in the desert, more than 50 of his former Compton congregants showed up to bid him a final farewell. Machuca was in the audience that day.

“That was an indicator of, ‘Oh yeah, he’s going to be good for us,’” she said.

A few days later, Valdovinos showed up unannounced to her office. “He said, ‘We’ve got a lot of work to do together,’” Machuca said with a laugh. “And we did it.”

Valdovinos plugged his own social service networks to Mecca’s existing ones. Those connections were vital as the pandemic finally hit. Our Lady of Guadalupe distributed more than 250,000 pounds of food last year, and the sight of a masked Valdovinos handing out bags of groceries to families or pushing around a dolly stacked with sacks and boxes made him a regular on local English- and Spanish-language television broadcasts.

Wilson last saw Valdovinos in December, just before his friend contracted COVID-19.

“We talked about his plans and the needs in Mecca, and I told him, ‘Francisco, just be careful,’” Wilson said. “‘You’re with people all the time.’ His death hit us hard, because he was so good at what he did.”

Two days after he died, Trinity Missions released a short video in his memory that’s as close to a personal manifesto as Valdovinos ever offered.

From inside Our Lady of Guadalupe, the priest declared: “You can preach. But we need to show, with action.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.