How Gavin Newsom went from landslide victory to fighting for his political survival

- Share via

In the giddy early hours of his landslide victory, California’s governor-elect struck a tone that signaled the grandiosity of his ambitions. “The sun is rising in the west, and the arc of history is bending in our direction,” Gavin Newsom told jubilant supporters on election night in November 2018.

There was some basis for a progressive Democrat’s fizzy confidence. Newsom had trounced his Republican rival with 62% of the vote. He would enter office with a massive budget surplus in a state where Democrats outnumber Republicans nearly 2 to 1, with supermajorities in both legislative houses.

He had survived a sex scandal as mayor of San Francisco, served eight years in the unglamorous job of lieutenant governor, and weathered claims that he was too ambitious, too slickly handsome, and too patrician-seeming — a supposed son of privilege whose bid for power was greased by his father’s big-money connections.

He had campaigned as a leader of resistance to the Republican White House, and promised that America’s most populous state would serve as an anti-Trump bulwark, as well as a continued engine of industry and innovation. “The future,” he told the election-night crowd, “belongs to California.”

Whether the future belongs to Gavin Newsom, 53, is now an open question. Voters on Sept. 14 will decide whether to cashier the governor before he has even completed his first term, in the second gubernatorial recall election in the state’s history.

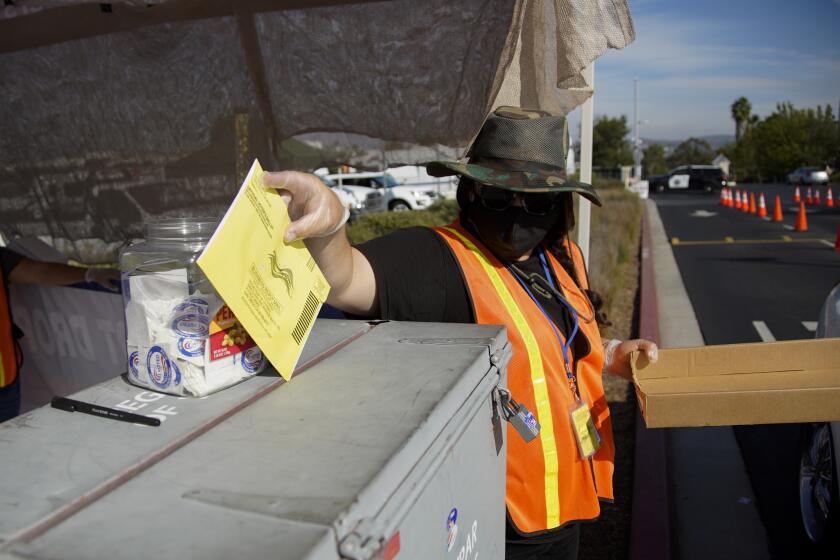

A primer on how voting by mail works, what the deadlines are, and how to track your ballot from the time it’s mailed to you to the time your vote is counted.

Among likely voters, 47% favor recall, while 50% want to keep him, according to a recent poll by UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies that was cosponsored by The Times. To hold onto his job, Newsom needs one vote more than 50%.

The story of a Democratic governor who finds himself fighting for political survival in a deep-blue state is hard to imagine without COVID-19, which has unleashed fury at leaders around the country.

“This is truly the pandemic recall — there’s no other way to describe it,” said Mark Baldassare, president of the Public Policy Institute of California. He said how governors have responded to the pandemic will define their legacies: “For governors elected in 2018, it’s not what they signed up for, but it’s what they’re going to be known for in history.”

Newsom’s early response to the pandemic, including the nation’s first statewide stay-at-home order, did not tank his approval rating among registered voters, and in September 2020 an IGS poll put it at 64%.

But by last month it had dropped to 50%. COVID fatigue was pervasive, the Delta variant was spreading, and Newsom — with regular, sometimes confusingly jargon-laden briefings — had made himself the public face of the state’s inconsistent pandemic response.

Apart from high taxes, homelessness and crime spikes, recall ads cite the pandemic-related shutdown of public schools, and billions of tax dollars lost under Newsom to unemployment fraud.

“The person in charge always gets too much credit when things are good, and too much blame when things are bad,” said Dan Schnur, a professor at UC Berkeley and USC and former Republican political consultant. “Most Californians know that Newsom didn’t cause the coronavirus, but he’s taking the lion’s share of the blame for how they feel it’s been handled.”

Newsom’s plight also owes in part to a Sacramento Superior Court Judge’s decision in November. Recall organizers claimed that Newsom’s pandemic shutdowns were hampering their effort to gather the necessary 1.5 million signatures, and the judge gave them four extra months to do so, a ruling Newsom did not challenge.

The same month, Newsom blundered into the French Laundry, a three-star Michelin restaurant in California’s wine country. Photos showed the governor celebrating a lobbyist friend’s birthday at the temple of haute cuisine, unmasked, at a time when he had been urging 40 million fellow Californians to avoid multifamily gatherings.

Caught, Newsom expressed contrition, but the struggling recall effort gained impetus, allowing free-floating misgivings about Newsom to find a focus. An out-of-touch elitist, a hypocrite, a multimillionaire who mingled with lobbyists when he thought people weren’t looking — it seemed an amalgam of his enemies’ caricatures of him.

The incident made “Saturday Night Live,” where an actor playing Newsom was introduced like this: “He’s hated by every single person in California except those 10 people he had dinner with in Napa that one time.”

Newsom had always struggled to combat perceptions that he was born into privilege. His late father, William Newsom, was a state appellate court justice who after retiring became a legal fixer to his friend Gordon Getty, scion of the Getty oil fortune. Getty invested in Newsom’s first business, the PlumpJack Wine and Spirits store, which opened in San Francisco in 1992, and Newsom’s businesses have since blossomed into a hospitality powerhouse of restaurants, hotels and bars.

San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown appointed Newsom to the Parking and Traffic Commission in 1996, and gave him a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors a year later.

Newsom later ran for mayor and won. Soon after taking office in 2004, the 36-year-old Newsom became a national figure by ordering the city clerk to issue same-sex wedding licenses, long before it was legal.

Thousands of people married before the state Supreme Court blocked it. Newsom suffered political blowback for years — including from Democrats who claimed he had handed Republicans a culture-war wedge issue — though his supporters portrayed his gesture as one of prescient moral boldness.

“Newsom is clearly somebody who wants to make history,” said Garry South, a longtime political consultant who advised Newsom on his brief 2010 campaign for governor. “This is not somebody who is going to nibble around the edges, and do something 3% better than his predecessor did.”

The telegenic mayor, with the bearing of an ex-jock and hair gelled straight back from a high forehead, provided gossip-page fodder after the collapse of his marriage to his first wife, Kimberly Guilfoyle. He appeared at a gala with a 19-year-old date, a model, who was seen holding a glass of wine. But San Franciscans did not seem especially troubled by headlines like “Mayor McHottie’s New Girlfriend — Half His Age.”

His reputation suffered, however, when he acknowledged that he had had an affair with his appointments secretary, who was married to his deputy chief of staff. He apologized and said he would get counseling for alcohol abuse.

When he ran for governor, his rivals derided him as a “Davos Democrat” and “Prince Gavin,” and Republican opponent John Cox’s campaign put up a website called “Fortunate $on.”

His supporters pushed an alternative narrative — the underdog story of a man with severe dyslexia whose parents split up when he was young, and who was raised by a mother who worked multiple jobs and took in foster kids to pay the bills.

His persona makes him “come off as somebody who is upper crust,” but “he earned the money,” South said. “He gets hit with all of this criticism about high-society, hoity-toity wine bars and all that stuff. But here’s somebody who came from a broken home, lived in basically a roadside motel in Marin County, and through hard work became a multimillionaire. This is not someone who’s inherited his wealth, and that’s one of the misconceptions about him.”

The early ballot return totals look good for Newsom and Democrats. But Republicans are betting on a late-breaking wave of pro-recall votes.

Still, for voters who don’t know much else about Newsom, the French Laundry incident seems to have special staying power.

“The average voter is not going to remember hospitalization rates and viral caseloads, but the impression of their governor going to a fancy restaurant with lobbyists during a shutdown is much easier to process, and much more likely to linger,” Schnur said.

“The most damaging gaffes in politics don’t create new impressions, they reinforce existing ones,” Schnur added. “A lot of voters already felt that he was someone of great privilege who didn’t understand what their daily lives were like. Going to the restaurant reinforced the idea that he could play by a different set of rules than they were permitted.”

As governor, Newsom imposed a moratorium on executions. As a leader of the anti-Trump resistance, he supported a measure requiring Donald Trump to release his tax returns and pulled California National Guard troops from the U.S.-Mexico border.

Newsom lost a useful political foil when voters turned Donald Trump out of the White House, but has worked to frame the recall as the work of Trump-friendly Republicans. His opposition gained a targetable face with the emergence of Larry Elder, a conservative talk-show host, as a front-runner.

“Newsom was having trouble running against Trump because Trump was no longer in office,” Schnur said. “He was having trouble running against the multi-candidate amorphous Republican blob. But Larry Elder is a living, breathing human being who says very controversial things. Newsom couldn’t have asked for anything more.”

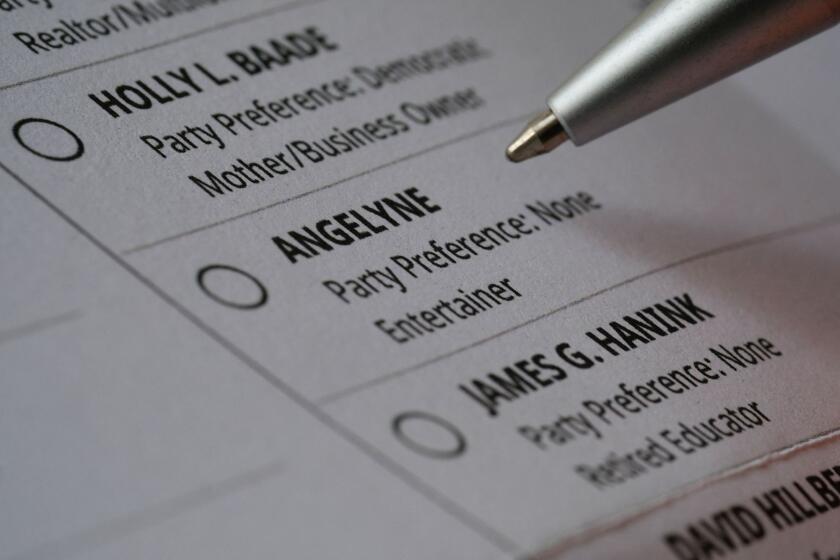

If voters choose to recall Newsom, they will pick among 46 candidates. Voters will find no prominent Democrats on the list, because Newsom urged them not to run. It is a risky all-or-nothing strategy.

The last time California held a gubernatorial recall, in 2003, it cost Democratic Gov. Gray Davis his job. Voters were fueled by anger over a car tax and power outages. His replacement, Arnold Schwarzenegger, was the last Republican governor to hold office in the state.

“When you run for office, you ought to be aware that the recall law and initiatives have been law for 111 years,” Davis said in a recent interview. “I don’t join the whiners and the moaners and the complainers. That’s just the way California is. That being said, Gavin Newsom had nothing to do with the arrival of the pandemic.”

He added, “I think he’s done a very good job given the hand he’s been dealt.”

Times staff writers Taryn Luna and Phil Willon, in Sacramento, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.