- Share via

He starts his shift before dawn working three industrial fryers at a frozen food factory. Jose Morales lifts a basket of burritos out of one vat of oil, hangs it to dry and dunks another in, all day juggling hot metal that has left mottled scars on his inner arms.

After work, he guides his 30-year-old stepdaughter Sandy Vazquez in a wheelchair through an out-patient clinic in Willowbrook. Jose is well short of 5 feet, his slight stature common in the part of Mexico where he grew up, where indigenous Nahua blood runs deep.

While he can barely see over Sandy’s head as he pushes, he has always been the big man in her life, the one who took her to Toys R Us to get her first princess Barbie dolls, the one who chased her tormentors away — and who never once questioned her when she said she was a girl.

For Jose and his wife, Reyna, their transgender daughter brought out an iron sense of purpose: they had to protect her until she found her own safe place.

They are a tight knot of a family mounting a bare-bones battle for the American Dream from an apartment next to the Century Freeway in South Los Angeles. In recent years, Sandy had starting to feel comfortable going out to parties with cousins and friends.

Her parents hoped she might be able to find a job and, some day, a partner who loved her.

The last year battered those hopes. The family caught COVID-19 in December and Reyna almost died of it before recovering. And in May, Sandy faced the prospect of losing her foot and lower leg from an infection.

Mortality has haunted them ever since with the dreaded question: What will she do when they’re gone?

::

Jose and Reyna met 26 years ago as they sewed shirts and dresses at a garment factory in downtown L.A. He had come to California a decade before, escaping an austere existence in the small city of Izúcar de Matamoros in the southern state of Puebla. His father had left the family when he was a baby, and his mother, unable to feed Jose and his brother, eventually indentured them to a local store owner. Morales was unloading boxes and arranging shelves at age 7 and never got more than four years of school. He joined the Army at 17 and came out two years later just as poor as he started.

Reyna left Acapulco for the same lack of opportunity. She needed to find work and send money back to her family so they could eat and have electricity.

As they chatted over their sewing machines, he showed genuine interest in her stories about the two young children she was raising alone, Sandy and her older brother, Arturo.

They went to quinceañeras, birthday parties, picnics in the park, lunches at McDonald’s — always with her kids. The pair moved into an apartment in the Broadway-Manchester neighborhood of South L.A. Sandy quickly grew to love Jose as her real dad. He affectionately pet-named her Gorda, his chubby girl.

Sandy was clear how she saw herself from at least age 3. When Reyna bought a skirt and blouse for her niece, Sandy wanted it. At first, Reyna indulged her as long as she stayed inside the house. At around age 6, Sandy started painting her nails and putting on lipstick. One day, she went out in the front yard in her makeup to dance. Reyna yanked her in before the neighbors could see, and spanked her. It was a moment of panic that still causes Reyna to tear up with regret.

Soon she came to realize she needed to let her child express herself. Reyna looked on with a mix of angst and joy as Sandy took her boombox out to the front yard and danced like Shakira or Thalia with a mop over her head. The neighbor boys laughed. Sandy didn’t seem to mind.

In Mexico, they knew that people like Sandy, as they became teenagers and older, were routinely beaten up, even killed. And Jose or Reyna were devout Catholics, going every Sunday to a church that wholly rejects the concept of transgender identity.

But they saw a simple, elemental truth: Sandy was their girl.

In grade school, Sandy still dressed like a boy and used her male birth name. She made friends and mostly avoided harassment, until she went with her mom to get her ears pierced. Soon after on the playground, a boy purposefully threw a utility ball at the side of her head when she wasn’t looking. Sandy came home with a bloody ear and a missing earring.

After that, letting her to go to school every day was agony for Reyna and Jose. They wanted to protect her, but they didn’t have the time to be there at lunch or after school. They worked in the garment factory all day, came home for dinner and a nap, and then cleaned offices for seven or eight hours at night.

By 2001, they had saved enough to buy a 1979 Chevy stake-bed truck and start a little mobile corner store from the back. Fresh food was hard to get in South L.A., so they stocked fruit and vegetables, as well as juices, sodas and candies. They called the business La Jefa Products after la jefa, the boss — Reyna — and soon made enough to buy a second truck.

They drove to downtown in the morning to stock up on supplies and sold around their neighborhood all day.

In four years, Reyna and Jose found a spacious home in South L.A., divided into two apartments, on a dead-end street shaded by eucalyptus trees on the Century Freeway embankment. The price was hefty, $510,000. But they qualified for subprime mortgage and second loan, putting only $12,000 down.

Jose felt he was escaping the crushing poverty that seemed to be his fate. And in a new neighborhood, and new school, Sandy felt she could finally be who she wanted to be.

On her first day of middle school, she wore jeans with a blouse, makeup and earrings — and introduced herself as Sandy.

The hatred did not take long to show its teeth. First it was just boys snickering and pointing. Then when teachers weren’t around, a group began to shove Sandy and hit her. Soon they were frisking her every day as if they were security guards, stealing any money she had, taking her phone, punching her.

“I told most of my teachers I was transgender,” Sandy says. “I wanted them to refer to me as she. But one of the teachers, she wasn’t having it. She’s like, ‘You’re a boy.’”

This provoked other students. “Is she a he or is he a she?” one asked.

“Pull his pants down and you can see who he is,” the teacher replied.

“We felt so powerless. To see how they were treating her and not being able to do anything. And all because she just wanted what she wanted to be.”

— Reyna Chautla, mother

Her parents didn’t speak English and couldn’t confront the teacher. But they had to try to stop the attacks.

Jose went to the school to confront the culprits. As Sandy came out after the bell, a boy stopped her and started taking her things.

“Hey, que traes?” Jose called out. What’s up? The boy bolted but Jose ran after him caught him, brought him to the principal and told him what happened.

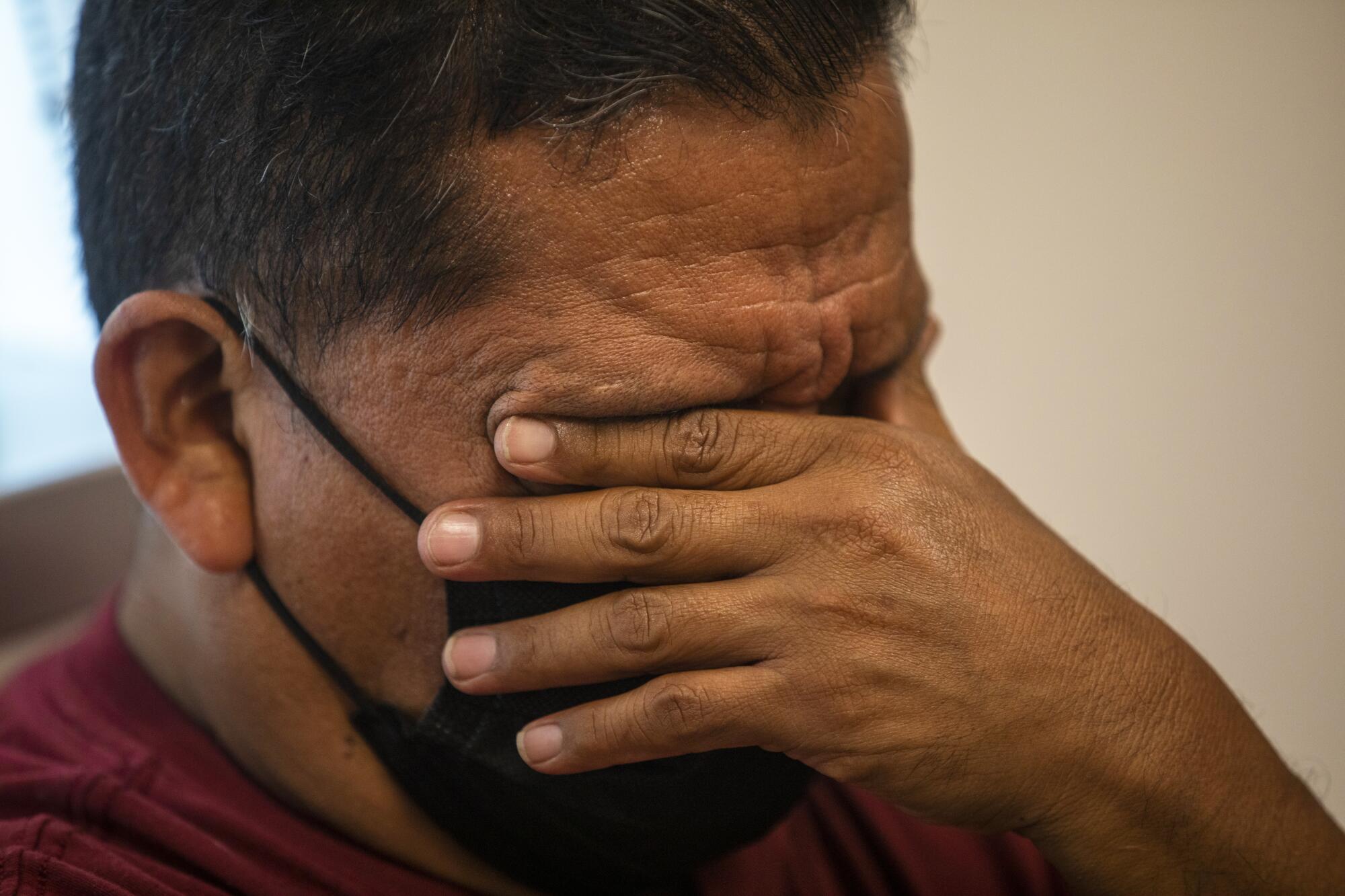

The memory of this time brings Reyna to sobs.

“We felt so powerless,” Reyna recalls. “To see how they were treating her and not being able to do anything. And all because she just wanted what she wanted to be.”

Sandy was reading more and more online about gender identity, and educating her parents. But she was isolated from any sense of community that could give her a sense of solidarity. “I didn’t know anybody who felt the same way as myself,” she says.

By the time Sandy landed in high school, the boys were bigger and the threats of violence more ominous. Her parents pulled her out.

Past coverage of transgender people perpetuated harmful stereotypes.

A therapist who regularly visited Sandy got her enrolled tuition-free at a private academic program in North Hollywood that specialized in teenagers who had troubles adapting in school. There were only two classes of 10 students each, and no one bothered her. Reyna drove her daughter the hour-plus trip each way every day, adding to increasingly long days at work.

Their business was coming under strain. People tend to notice good fortune in places where it is scarce, and neighbors started running their own trucks. Worse, a clique of the 18th Street Gang was starting a sideline racket extorting the street vendors.

First it was just young teenagers asking for a free soda here, a chocolate bar there. But word spread and higher-ups in the clica confronted Jose demanding a weekly payment of $100 for each truck. They knew the extortionists since they were toddlers.

Jose and Reyna worked harder to make up for diminishing returns. When she dropped Sandy at home after school, she made her do the laundry, clean the kitchen and have the family dinner ready, while mom went back to work.

The gang threat took a toll on Reyna, who was terrified Jose would be shot. She had heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes, and the stress made her health worse. As an undocumented immigrant, her Medi-Cal only covered emergency care.

But the big blow came from the banks. Two years after they signed their loan documents, their lenders raised their adjustable interest rates. Their mortgage payment jumped from $3,025 to $5,200.

The lead lender foreclosed as they continued to live in the back apartment and pay rent to a new owner. Jose swallowed the devastating blow and did the only thing he could do. Keep working.

In the streets, the gangs just got more menacing.

“La renta!” shouted a pistol-packing gangbanger in a wheelchair who was called El Wheelo.

“No tengo,” Jose said. He didn’t have it.

Ultimately, it was not the gangs but the competition from other vendors that spelled the death for La Jefa Products. Jose and Reyna, who was increasingly ill, sold the trucks as he started working at different factories through a temp agency.

After her junior year of high school, Sandy didn’t return to public school. She rarely left the apartment, depressed for months on end. She was scared to go out alone and was shy in ways she never had been. She didn’t want to work or go to college. She couldn’t envision her future and developed a fantasy that she didn’t have long to live.

The forced homecoming of students because of COVID-19 has been painful for those whose families do not know of or reject their LGBTQ identities.

When she did go out with her cousins and their friends, Reyna would not sleep until Sandy got home, thinking about news stories she’d seen about transgender women being killed in the street.

One summer day in 2018, her cousins persuaded Sandy to go to Hurricane Harbor, the water park in Santa Clarita. Walking barefoot on the hot pavement, she got a large blister on her foot. At 28, Sandy had diabetes like her mother, and in her depression, did not bother taking insulin or monitoring her sugar or weight, enabling the disease to damage the nerves and blood vessels in her feet.

The blister got infected and she went to the emergency room at Martin Luther King Community Hospital. A podiatrist, Dr. Myron Hall, cleaned out the wound and bandaged it, and told her to visit him at the out-patient clinic periodically to check on it.

She got better, but her mom’s health continued to decline and in December, with her underlying conditions, she was hospitalized for severe COVID-19. All Reyna could think about was leaving Sandy behind and putting the full burden of supporting her on Jose. If she recovered, she wanted to ensure father and daughter were seen as family in the eyes of God.

::

The wedding was an act of their enduring hope. Reyna bought a custom-made pearl dress with gold lace from a storefront in Huntington Park. Jose wore a black suit and gold tie to match the dress. Sandy did Reyna’s makeup, and sewed COVID masks made from the dress material. On April 24, the couple married at St. Michael’s Church, the chapel they went to every Sunday.

Sandy was brightening up bit by bit, going out with her cousins and friends more often. Jose hoped she might get a job, maybe working in a nail salon, and find her life’s path. Then a pedicurist accidentally reopened the wound on her foot. Dr. Hall cleaned it out again, but weeks later, Sandy walked on it too early, and got it wet in the shower.

On May 14, her foot throbbed in pain as she ran a fever and vomited. The wound-care nurse told her to go to the hospital immediately. Dr. Hall found necrotizing fasciitis — flesh eating bacteria — running through her foot up the inside of her leg. She was close to going into shock and dying. Hall did surgery that night to remove a piece on the side of the foot and told her she might need several more procedures before he would know if he could save her leg.

Reyna’s mother had lost her foot to diabetic amputation in Acapulco. She pictured Sandy unable to get around the house, bed-bound and more depressed, no job, no partner, no family of her own, no end to her parents’ protecting her.

The next day, Reyna, 60, suffered a stroke that paralyzed half her body.

After three more surgeries, Dr. Hall saved Sandy’s foot, her toenails still painted white for the wedding.

When she got home, her dad asked, with his usual practicality, “Are you hungry Gorda? What can I make you?”

These days Reyna and Sandy lie in bed all day under a poster-size photo of the wedding with Jose standing on his tiptoes. Arturo and his 12-year-old daughter, Destiny, come and go from work and school. Mom watches her favorite Turkish telenovelas dubbed in Spanish, Sandy keeps her foot elevated while using TikTok. Jose, 55, arrives home from his shift over the fryers in Cudahy and helps Reyna get to the bathroom, and then sits her in a chair; her insurance does not cover the rehabilitative therapy that her doctors told her could help her walk again one day.

Jose takes Sandy to see Dr. Hall at the wound care clinic. He shops for groceries and cooks their dinners and they all sit at the table by the back window, talking, teasing, worrying, laughing.

Jose asks if the food is good.

Sandy shrugs. “Eh, mas o menos,”she says — more or less, a running joke since her dad took over the cooking.

Jose and Reyna see God’s plan in Sandy keeping her foot. And for this, they remain steadfast: she will find her place.

The celebration holds special significance for an Eastside community that lacks safe queer spaces compared with West Hollywood and other areas.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.