‘I would use my voice better next time’: Racist attacks inspire Asian Americans to fight back

- Share via

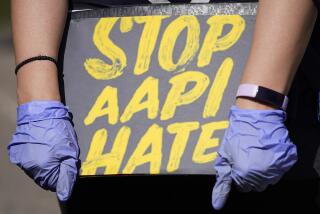

For some Asian Americans who have erred on the side of caution when confronted by racism, this year has changed everything.

As the coronavirus pandemic worsened, then-President Trump referred to the “kung flu” and “Chinese virus.”

Asian Americans were accused by strangers of spreading the virus and told to go back where they came from. Elderly Asians walking down the street were violently shoved to the ground by strangers who approached them with no clear motive other than to hurt a vulnerable person.

The hate and violence culminated last week in a massacre at Atlanta-area spas. A 21-year-old gunman killed eight people, including six Asian women, telling investigators he was battling a sex addiction and trying to eliminate temptation.

Here are the stories of three Asian Americans who have dealt with racism all their lives and are now determined to speak up.

Picking his battles? Not anymore

When Christopher Kim was in first grade, a kid on the playground called him “Chinese boy.”

He complained to a teacher, but she looked at him and walked away.

His parents said, “Try not to let that worry you too much. They’re just ignorant. They just don’t know any better.”

There were few other Asians in Shreveport, La., where Kim was born and raised.

He tried to explain that he was of Korean descent, but his classmates only seemed familiar with China and Japan.

“Early on, there was that feeling of exclusion and being the perpetual foreigner, so to speak,” he said.

In sixth grade, a group of white boys surrounded him and taunted him for being Asian.

Kim wanted to hit them. But he knew that would not end well.

“I did my best to just keep my mouth shut. I knew they wanted a reaction out of me. So I just kind of took it,” he said. “It was a very humiliating experience, but I knew from every angle it was a losing situation. I knew it was just something I had to suffer through in silence.... I knew if it escalated beyond the verbal harassment, it was going to end badly, really it was going to end even worse than the harassment. It’s one of those things where you really have to pick your battles.”

Kim, 34, attended graduate school in public health at UCLA and lived in San Diego until recently.

Last November, he moved to Dallas, partly to be closer to his parents. The recent attacks on elderly Asians have unnerved him. And he is no longer suffering in silence.

“I’m at the point in my life where I’m kind of like, ‘This has gone far enough.’ I can’t stay silent anymore, in the background,” he said. “I have to speak up and really say something about this and really raise awareness that this is a serious issue and it does cost people their lives.”

‘If you don’t speak up, people are going to bully you’

Last February in San Mateo, Renee Lau’s grandmother returned from walking the dog with a disturbing story.

A white woman had approached her and asked, “Do you speak English? Are you Chinese?”

She speaks little English, so she could only nod in response. Then, the woman said, “Go back to China.”

Lau, 28, marched outside with her grandmother looking for the woman.

After spotting her, Lau initially took a cautious tone: “Excuse me, did you say this to my grandma?”

“Well she doesn’t speak English, does she?” the woman responded.

“That doesn’t matter, that’s rude,” Lau said. “You just went up to her and said all this rude stuff to her because of the fact that she can’t defend herself.”

The woman then said your “kind of people” are corrupt and that “no one wants you here — you have to go back to China.”

Lau’s grandmother urged her to leave and “not make it a big deal.”

Instead, Lau snapped a photo of the woman and reported her to the apartment’s management. Nothing happened.

But the dynamic changed between her grandmother and the harasser. Her grandmother said she felt more confident after Lau’s defense. The harasser now avoids them.

“If I didn’t say anything, maybe every time they have an encounter, she might say something rude,” Lau said. “Good things come out of it. You just have to speak up or else it kind of enables the bullies.”

After all the assaults on elderly Asians, she is scared for her father and grandmother. But she believes that speaking up can help.

In high school, she was on the bus when a man came up to her and tried to get her attention.

When she ignored him, he said loudly: “Guess you don’t speak English.”

She answered, in English.

“He got embarrassed because he didn’t think I was going to respond,” Lau said. “That’s when I learned that if you don’t speak up, people are going to bully you, especially if they think you don’t speak English.”

‘I would use my voice better next time’

It has been years since high school, but the image is still burned in Sumalee Montano’s mind.

She was running for student council president. On election day, someone spray-painted “nuke the g—” near the entrance of the school in central Ohio.

The principal called her into his office. The three boys who had painted the racist message were there, too, and apologized to her. They were friends of her opponent.

But that only made the incident scarier.

“I was just like, ‘Why am I, a short, small, Asian girl alone in an office with a big, tall, white, male principal and three other big, tall, white guys, all jocks, who basically just threatened me?’ All I wanted to do was get out of there as fast as I could,” she said. “It was so intimidating and frightening to be alone in that situation.”

The boys were not severely punished, she said. Montano, who is half-Filipino and half-Thai, won the election.

Another time, her family was on a road trip when a group of white men jumped out of a pickup truck carrying bats and big sticks and yelling about “foreigners.”

Her father looked as if he might fight back, but her mother screamed at him to get in the car and leave.

They drove away, with Montano crying in the backseat.

“That was one of the scariest moments of my childhood, to know that these men wanted to kill us just because of the way we looked,” she said. She was 13 or 14 at the time.

In her Los Angeles neighborhood a few weeks ago, an unmasked woman breathed in Montano’s face, then leaned into her 8-year-old son’s face and said in a snide tone, “Oh, aren’t you cute?”

Montano didn’t say anything. She was too shocked. And she second-guessed her instinct that the woman’s behavior was racially motivated.

“I can never prove to anyone that it was racist without her hurling racial slurs at us, but you have to wonder: Would she have done that to us if I was a man? Would she have done that to me if I was white like her?” said Montano, an actress and voice-over artist.

Her son’s assessment was less complicated.

“She did that on purpose, Mamma,” the boy told her.

Now, she has regrets.

“I promised him it would never happen again and I would use my voice better next time,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.