Rural California schools have been open for months. It’s taken a learning curve

- Share via

WEAVERVILLE, Calif. — Tabatha Plew quit her good-paying construction job in August, pulled her kids out of a Central Valley school they loved and moved seven hours north to this tiny town in Trinity County.

Like a lot of rural communities, Weaverville in recent years has seen more people leaving than arriving, but it had a golden commodity Plew couldn’t find at home in Fresno County for her three children: open classrooms that promised a desk in front of a teacher.

“I packed them up, and I told my husband, ‘We love you. See you on the weekends,’” said Plew, who moved into her in-laws’ home in Weaverville. “This was the highest-paying job I’ve ever had, and, you know, the money didn’t mean anything when my kids were struggling.”

As schools in Los Angeles and elsewhere debate the particulars of bringing students and teachers back to classrooms after a year of distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous public school campuses have been open for months in rural Northern California.

There were far fewer COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths in this sparsely populated region than in urban areas, where campus reopenings have hinged on lengthy teachers union negotiations and hesitancy among parents about returning often reflects the disproportionate horrors wrought by the coronavirus in working-class Latino and Black neighborhoods. In hard-hit Los Angeles County, schools in wealthier, whiter areas with fewer cases have opted to reopen faster this spring than those in less affluent communities of color.

When the academic year began, state rules allowed K-12 campuses to resume in-person instruction if a county stayed off the now-defunct state watchlist for 14 consecutive days. The counties that first met the reopening criteria were primarily rural.

For those that reopened first, this school year has been an education.

In Weaverville, population 3,100, the lure of in-person instruction proved so great that the roughly 700-student K-12 Trinity Alps Unified School District, which had budgeted for declining enrollment, gained about 30 pupils whose families moved in from other areas, administrators said.

The district opened its elementary, middle and high school classes in August, when there had been just 10 confirmed coronavirus cases in mountainous Trinity County.

It was a decision for which Supt. Jaime Green said he caught a lot of flak from outside the community. He was bombarded with emails calling him irresponsible and reckless. In the days before the school year started, he spoke often with superintendents in neighboring counties who kept asking one another: “OK, are you really reopening?” because they didn’t want to go it alone.

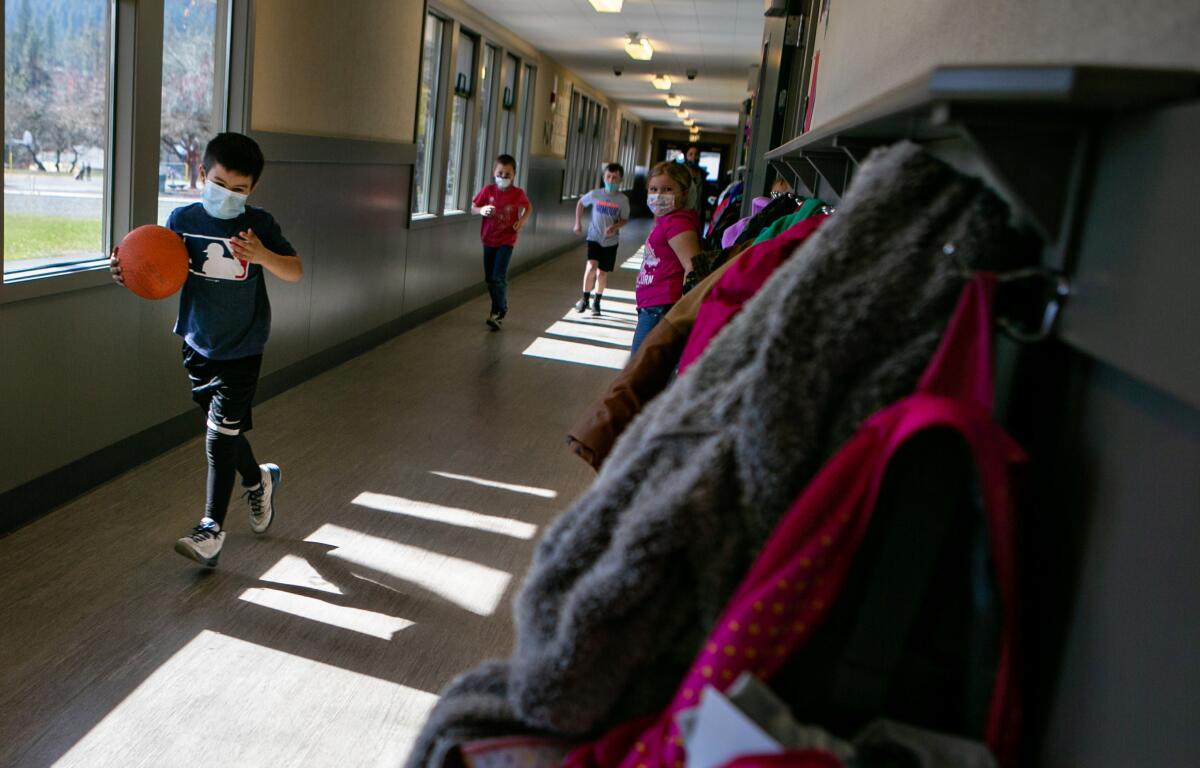

Green said that he did not have any staff members object to teaching on campus and that the vast majority of students have returned. Masks are required for students in grades three and up. There were no sports or pep rallies before last month. Prom is canceled. Hand sanitizer is everywhere.

“There are risks. COVID’s dangerous. We have never said that it wasn’t. We are very apt to that, and we keep our eyes on it, and we have medical personnel checking our schools all the time,” Green said. “If we have to close, we close.”

Since August, the high school closed its campus and switched to distance learning for 17 days because too many staff members and students had been potentially exposed to the virus. At the elementary school, the transitional kindergarten and kindergarten each has been quarantined because of potential exposure, but administrators say there have been no cases connected to the site.

Green was stuck in bed with COVID-19 for several days last month. He said the financially strapped district is using COVID-19 relief money to pay teachers’ salaries if they have to stay home so they don’t burn through their sick time and come to work while feeling ill.

Sophomore James Norman, 15, said he was grateful for a fairly normal school year.

“I don’t really like talking through the screen,” he said. “I feel like I’m talking to nobody, and I can’t focus as much as when I’m in the classroom. From here, I feel like the only way is up.”

At Weaverville Elementary, Principal Katie Poburko said young students are still catching up. Reading scores tumbled after schools closed last spring, but students in transitional kindergarten through fifth grade read for 90 minutes each day and have made gains. Saturday school is offered once a month. Summer school is planned.

Middle schoolers were given planners a few months into the school year “because they just forgot how to be students and what time management looks like,” Poburko said.

Poburko was speaking in a second-grade classroom where Plew’s son Stephen Bo was coloring and wearing a mask with dinosaurs on it.

“What’s the coolest thing about coming to school here?” she asked him.

“Um, it’s fun!” he replied, showing off his new cowboy boots.

Distance learning in Fresno County last spring for Plew’s children meant an unreliable internet connection that kept booting Kenny, 14, out of class. High-achieving Koral, 11, grew frustrated by glitchy technology that made it hard to turn in her homework. And 7-year-old Stephen Bo, who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, was overstimulated — and overwhelmed — in his first-grade Zoom class.

Plew, whose family had just started construction on their dream home in Fresno County, said her children have thrived in Weaverville. She and her husband are trying to figure out what to do if their home school does not fully reopen in the fall. They’ve thought about private school, which is expensive for three kids. And they’ve seriously considered permanently relocating to Trinity County or out of state.

In nearby Junction City — population 682 — the elementary school opened in August, with its 75 students split into groups of 10 to 12 to maintain social distance, said Supt.-Principal Christine Camara. Kids are spread all over campus, including the cafeteria and her office.

To keep student groups small, Camara and other nonteaching staff members work in classrooms. Camara teaches special education in the mornings and science in the afternoons.

“There aren’t many [substitute teachers] available in our area, so it makes it difficult when a staff member can’t be at school,” she said in an email. “Even releasing staff to get COVID tested and vaccinated has been challenging.”

Every student was issued a Chromebook, but, like many rural communities, mountainous Junction City has spotty cellphone service and less access to high-speed, at-home internet required for distance learning.

In Modoc County — which did not report a coronavirus case until July 28 and confirmed its first death Dec. 29 — Tom O’Malley, superintendent of the Modoc Joint Unified School District in Alturas, said he initially got pushback from parents furious their children would have to wear masks when classes opened in August. But students have adjusted well, he said, and the schools have not had to close for a single day.

“This year, to be honest, has not been about learning,” he said. “It’s been about getting the kids here every day and social and emotional stuff.”

About 65% of the 830 or so students in the district are socioeconomically disadvantaged, O’Malley said. There is a lot of substance abuse in the community, and a lot of child abuse, he said.

“We are the source of safety for a lot of our kids, and we wanted to get eyes on them,” O’Malley said.

About four weeks into the school year, “we had a whole bunch of kids melt down,” O’Malley said. After their initial excitement about being back in class wore off, they let their guards down and confided in school staff about the trauma and stress of the previous few months.

In a typical year, he said, the district has one or two students who are pre-suicidal with whom officials have “strong interventions.” Last fall, there were nine such students in three weeks.

“When the kids have a plan and can tell you about it, it’s serious,” he said. “They had plans and means. It’s scary.... They hadn’t had a lot of people to talk to, and they came back and realized they have these adults they trust that care about them, and they don’t have to take this on by themselves.”

In Siskiyou County, enrollment at Weed Elementary School shot up 34%, from 254 students last spring to 341 students this academic year because parents desperate for in-person classes transferred their children, said Supt.-Principal Jon Ray.

The school had to cap enrollment to keep classes limited to 16 students, and there now is a waitlist for on-campus instruction, he said. Ray had to hire three distance-learning teachers and three additional custodians to frequently sanitize the facilities.

He also hired three licensed marriage and family therapists. After schools closed last spring, he said, some students were exposed to domestic violence and other trauma.

“When we reopened, we had what I’ll call a honeymoon period,” Ray said. “Everyone was getting along. It was going great. After that, we started seeing kids just having difficulties and discovered a huge mental health crisis.”

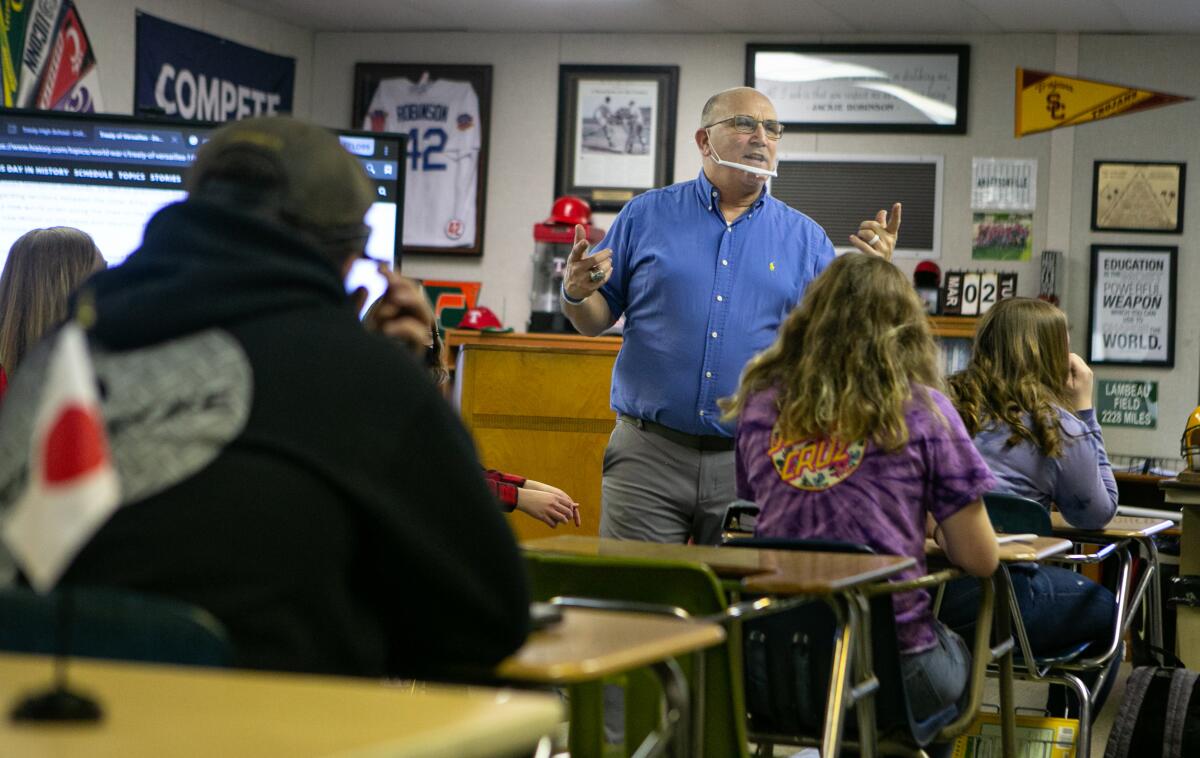

Thirty miles north, Yreka High School has been doing hybrid learning — with students spending half their time on campus and half attending class online — the entire school year.

Sitting at his desk behind a plexiglass barrier this month, Yreka Union High School District Supt. Mark Greenfield said that, so far, no coronavirus cases have been linked to transmission on campus. The school transitioned to full-time distance learning for about a month this winter as case numbers rose in the county, but it reopened the campus in January.

On Greenfield’s wall hangs a map of the sprawling high school district, which stretches deep into the mountains. Though Siskiyou County — home to 43,500 people in a space eight times larger than Orange County — allows for natural social distancing, its size lends itself to what Greenfield said was a major factor in reopening Yreka campuses: isolation.

“I think the difference between rural schools and urban schools is we’ve got kids that don’t see other people unless they’re here in town and at school,” Greenfield said. “They live in wilderness areas.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.