- Share via

In the spring, while New York suffered untold devastation from the COVID-19 pandemic, California was so successful in keeping the virus at bay that at least one expert called it the “California miracle.”

So when the coronavirus began to proliferate with unprecedented fury in November, transforming California into the epicenter of the pandemic, health experts and residents struggled to understand what had gone wrong.

Now, with the crisis showing signs of easing, the main reason for the catastrophic surge is coming into focus: a false confidence that the pandemic could be kept in check. For the public, that complacency showed up in fatigue and frustration over safety restrictions. Officials, for their part, were caught off-guard by how rapidly, and how broadly, the virus spread once the numbers began to climb.

By Christmas, so many patients struggling to breathe needed to be hospitalized in California that emergency rooms in large swaths of the state closed to ambulances as doctors stuffed patients in hospital corridors. The holiday surge has so far killed more than 18,100 Californians, more than doubling the state’s total death toll from the pandemic in less than three months.

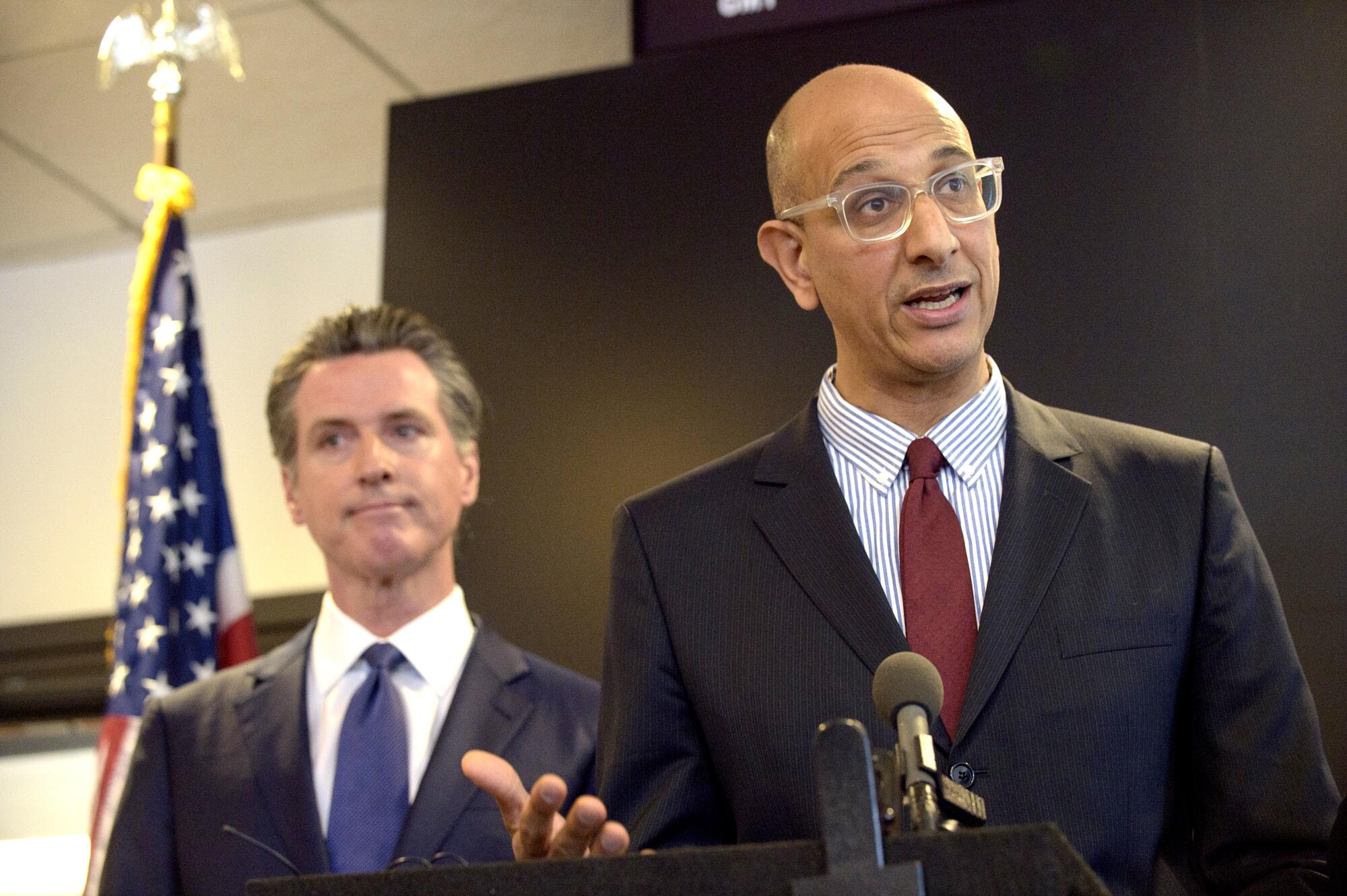

“We never, never planned for something like this to happen,” California Health and Human Services Secretary Dr. Mark Ghaly said in a recent interview. The state’s mask mandates, business closures and stay-at-home orders, he said, “were all designed to try to avoid this.”

There are many possible theories as to why California was hit so hard starting in the late fall, including the introduction of more contagious strains of the virus, dry weather that made transmission easier and a higher percentage of the population being vulnerable to the disease because relatively few Californians had been infected up to that point.

COVID-19 deaths still stalking California at alarming levels even as cases continue to flatten

But most experts point to changes in behavior: people beginning to abandon staying home, social distancing while out and other precautions that experts say curb transmission of the coronavirus.

In the fall, masking dipped in California while social distancing fell to the lowest levels since the pandemic began, according to one analysis. Meanwhile, the numbers of Californians attending gatherings with 10 or more people reached the highest level since before March, according to a USC survey.

And when a coronavirus wave started building in late October, Californians didn’t cut down on their risky activities as quickly as they had earlier in the pandemic. Instead, the state faced the alarming prospect of a series of amplifying events with Halloween, Thanksgiving, Hanukkah and Christmas, followed by New Year’s.

The complacency caught officials off-guard and in turn sealed the state’s fate, as the prevalence of the virus crossed a tipping point into explosive growth, experts say.

“Had we had the same level of compliance that existed with the first wave, we could have avoided the magnitude,” said UCLA epidemiologist Dr. Robert Kim-Farley. “This wave has turned into a tsunami.”

Though people let their guard down across the nation as the pandemic wore on, California requires a higher degree of compliance to stave off a New York-style disaster, given the state’s high rates of poverty and its relatively low number of hospital beds, experts say.

Some attribute the waning cooperation simply to fatigue. Others argue that a dizzying array of health orders exhausted and confused Californians and sparked backlash.

L.A. was far more vulnerable to an extreme crisis from the coronavirus than nearly anywhere else in the nation.

Though epidemiologists warned the nation of a deadly winter wave fueled by colder weather, they didn’t predict that temperate California would become the prime example. For the six-day period that ended on New Year’s Day, California had the highest per capita COVID-19 death rate in the nation.

“Did I expect to see December and January this bad? Yes. But I expected to see it throughout the United States,” said UC Berkeley public health professor Dr. John Swartzberg. “That’s what I think the shocker has been.”

To be clear, even after the awful surge, California maintains a comparatively low per-capita COVID-19 death rate overall, ranking 37th out of the 50 states. And, following several weeks of horror, the state appears to have finally turned the corner as coronavirus cases and hospitalizations begin to drop, though new variants of the virus have raised fresh concerns.

‘COVID resentment’

In the eyes of Ghaly, who leads the state’s response to the pandemic, what went wrong in California comes down to COVID fatigue, or what he sometimes calls “COVID resentment.”

With Halloween and the championships of the Lakers and Dodgers, lonely Californians exploited an opportunity to socialize, he said. Even his own mother, who lives in San Francisco, began pleading with him to let her visit him and his kids in Los Angeles.

“She calls every day. And she says, ‘But when is it ready? When can I come visit?’” Ghaly said. “So I can’t even imagine where you don’t have the same level of information — it’s not constantly in your face — how hard it must be to not gather.”

Officials, too, were feeling hopeful in the fall that they had figured out how to manage the pandemic. In L.A. County, nail salons and indoor malls reopened. Some local officials anticipated that indoor restaurant dining and indoor gyms would reopen later in the fall.

The public followed their lead. Californians’ perceived risk of catching the coronavirus fell to the lowest level since the pandemic began, while the percentage of Californians who had close contact with people they didn’t live with peaked, according to the USC survey.

‘You pay a price for your success’

At the same time, Californians were moving around their communities at levels not seen since before the statewide stay-at-home order in March, according to cellphone mobility data analyzed by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

The spread of the coronavirus began to quicken in the state, due to a false sense of security aided by low case numbers, said IHME epidemiologist Ali Mokdad.

“You pay a price for your success,” he said. “The advice should be: ‘This is here to stay.’ ... This virus is so stubborn. You make a tiny little mistake, it will go after that mistake.”

When officials began warning in late October for people to limit their activities as coronavirus cases began to surge, the pleas increasingly fell on deaf ears.

Some Californians were distrustful of officials after Gov. Gavin Newsom ate at the French Laundry restaurant in defiance of his own health orders. Others were angry after months of unemployment with little economic help from the federal government or were simply fed up with living an isolated, walled-in version of their lives.

And after months of relative quiet in the hospitals, for many, the risk no longer seemed imminent.

On Nov. 16, a frustrated Dr. Wilma Wooten, the San Diego County health officer, said she had hoped a warning issued a month earlier about the resurgence of the pandemic “would mark a change in the public’s personal and collective behavior. It is quite obvious, however, that it did not.”

Some of the inertia felt California-specific, said UC San Francisco epidemiologist Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo. Whereas other states reopened schools and many outdoor, low-risk activities when case numbers were low, California’s more restrictive orders created a feeling of being in lockdown for 10 months, she said.

“I think Californians are more fatigued. They’re fatigued in a way that’s uniquely Californian,” she said. “We don’t experience the fruits of all of the good work that we’ve done because we’re never quite open and so it feels hard to close down, even [when we’re] hearing what is a real message from our public health officials: that we’re in a crisis right now.”

The backlash begins

There is a relatively small window for officials to act to stop a devastating surge of the coronavirus, since each new infection makes it more likely that more people will become infected. California officials, seeing the writing on the wall, rushed to put in place policies in November and December to try to slow the spread.

But the orders engendered far wider criticism than had been seen up to that point. Of particular contention were a statewide curfew for most of the state banning many activities after 10 p.m., a ban on outdoor dining, closure of playgrounds — which was eventually reversed amid backlash — and the prohibition of most outdoor gatherings of any size. That malls remained open while going on a masked walk with a friend violated the health order became fodder for jokes, and frustration.

Malls have continued to welcome holiday shoppers, even as officials have banned other forms of gathering amid a massive surge in coronavirus cases.

While many experts have backed these rules, others wonder if they ended up fueling a backlash. University of Florida epidemiologist Cindy Prins said she thinks California may have benefited from being more liberal with its rules for outdoor spaces.

“We’re all running a big experiment, because I don’t think we know exactly what the right point is to have people be compliant,” she said. “I don’t think all closed is the way to go. I don’t think all open is the way to go. I’m not sure where the happy medium is.”

Some law enforcement officials in Sacramento, Orange, Fresno, Riverside and San Bernardino counties said they would not enforce Newsom’s stay-at-home orders.

In L.A. County, some local politicians were incensed at the outdoor dining ban and began accusing county scientists of not following the science. County Supervisor Janice Hahn, who opposed the ban, said it became the final straw for residents: “Up until that point, I felt like we had the public’s trust,” she said in an interview.

The loud debate around these orders dissolved the united front needed to gain adherence to public health measures, experts say.

By late December, 40,000 Californians were testing positive for the coronavirus each day and 20,000 were in the hospital. While the pushback to the regulations had been much more severe in the southern part of the state, the surge was too — a sign of how important widespread cooperation with the rules can be, experts say.

The flood of new cases has exacted a horrific toll, with more than 500 Californians dying every day at the peak, and hospitals so crowded ill patients have had to wait as long as 17 hours to even just enter the emergency room.

‘The virus will find a way’

Critics, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, have said that the disaster in California is proof that mask mandates and stay-at-home orders don’t work. Experts say they can be effective, but California simply requires a much higher rate of compliance with these measures than a state such as Florida due to its innate vulnerabilities.

California has the nation’s third-lowest ratio of hospital beds to residents, so the threshold for pushing ICUs to the brink is relatively low. The state is also home to several cities that are major travel hubs, reliant on public transportation, with a high percentage of residents living in poverty and in overcrowded homes, where the virus is more likely to spread due to the close quarters.

While 55% of California’s residents live in counties with high “social vulnerability” score — a measure of how severely affected a region may be by a natural disaster or disease outbreak — fewer than a quarter of Floridians do.

That California could somehow avoid a large COVID-19 surge without a China-style lockdown was naive, said UC Irvine public health professor Andrew Noymer. There is some randomness in when outbreaks hit — Illinois’ worst surge came in November while California’s hit in December — but there won’t be safety from the pandemic until herd immunity via a vaccine is achieved, he said.

“This virus will find a way,” Noymer said. “No place in the United States is just going to somehow evade this.”

This week, however, hope arrived in the form of small percentages. The number of people in the hospital with COVID-19 in California has begun to decline, as have new case numbers.

The shifts are probably due to Californians’ decline in activity, which began to gradually decrease in November and hit a low — the lowest since May — in December, due to a combination of local and state rules, increased warnings and the public’s natural tendency to become more cautious after witnessing the devastation around them, experts say.

As is usually the case with the pandemic, the consequences of people’s actions don’t become evident for several weeks.

Despite signs that COVID-19 may be receding, a top Los Angeles County official warned the situation remains precarious.

Ghaly said he thinks this progress shows that the state can control the pandemic, a spot of good news in a surge where the story has often been “that things have only gone wrong.”

Overall too, California has tallied 90 deaths for every 100,000 Californians since the pandemic began, compared with 212 per 100,000 people in New York, 158 out of 100,000 in Illinois and 119 out of 100,000 in Florida. In other words, if California had the same death rate as Florida, California would have a cumulative death toll of more than 47,000, instead of the 35,000 it does today.

“It’s hard to find successes in this, but ... improvements are successes,” Ghaly said. “What we’ve done in California has worked for us, and has done what I’d hoped it had done, which is saved a lot of lives.”

Times staff writers Sean Greene and Deborah Netburn contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.