She was his best friend. And she led him to his death

- Share via

It was fifth period at Panorama High School when Brayan Andino’s best friend dropped into his class and asked if he wanted to cut school to smoke some weed.

They slipped out to a table and waited until no adults were looking to steal away. Brayan, a stocky 16-year-old who claimed membership in a gang he didn’t belong to and trusted people he shouldn’t, asked where they were going.

Lake Balboa Park, she proposed. If it sounded spontaneous to Brayan, it wasn’t. She would later testify that several of his 10th-grade classmates had spent the previous week planning how to kill him, and that she, his closest friend, was the bait in the trap.

In a cramped juvenile courtroom in Sylmar, that friend and a second girl described how in 2017 they helped boys and young men affiliated with the MS-13 street gang coax Brayan to Lake Balboa Park, then into a car that carried him into the mountains above the San Fernando Valley, where he was stabbed and bludgeoned to death and thrown off a cliff.

The girls’ testimony, delivered in the murder trial of a former classmate, marked the first full account of how Brayan’s death was planned and carried out. The trial also presented a troubling portrait of Panorama High, whose resident police officer testified that MS-13 had established a cell on campus.

On Sept. 17, Superior Court Judge Fred J. Fujioka found Oscar Mendez, now 18 but 15 at the time of the killing, guilty of murder and gang conspiracy. But even at its end, after hours of testimony from the girls, detectives and gang experts, the trial did not fully explain why, as a prosecutor put it in his closing argument, a group of teenagers had embraced “a culture of death.”

::

Brayan Alejandro Andino was big for his age — much bigger than classmates who ran with MS-13, also known as Mara Salvatrucha. He was born in Honduras and came to the United States with his brother in 2013. Their mother eventually followed the boys north, and they settled in Van Nuys.

At Robert Fulton Middle School, Brayan met a short, chubby girl from El Salvador who would become his closest friend. The Times is not naming this girl or the other witness who testified because they face a serious threat of retaliation.

When Brayan enrolled at Panorama High, a probation officer assigned to the school warned the campus police officer, Chad Phillippi, that the boy had been challenging students affiliated with MS-13, claiming he belonged to their archrival, 18th Street. He had scrawled on his backpack: “F— MS.”

At best, Brayan was an 18th Street wannabe, according to court testimony. He photographed himself flashing the gang’s sign, but there was no indication that he actually ran with its members.

Phillippi called Brayan into his office. “We discussed how dangerous it would be for him to be claiming 18th Street at my school,” the officer testified, “knowing that I had an MS-13 clique on my campus.”

The clique hung out near the quad, Phillippi recalled, a small group of boys and girls, diminutive in stature, all recently arrived from El Salvador. They represented only a fraction of the Salvadoran children who had enrolled at Panorama High after leaving their homeland, which in the last 50 years has been riven by civil war, beset with poverty and haunted by violence between MS-13 and 18th Street, gangs that were born in Los Angeles before being exported to Central America.

In coming to Panorama City and nearby working-class neighborhoods, the children had landed in the territory of an MS-13 clique, the Fultons. The boys who affiliated with MS-13 didn’t dress like typical gang members. Although they wore Nike Cortez sneakers — standard issue for L.A. street gangs — they sported stylish jeans and shirts, and hats bearing the logos of the Los Angeles Rams and the Chicago Bulls, a nod to the gang’s obsession with horns, Phillippi said.

When he searched their school bags, Phillippi saw they had doodled pictures of devils in their notebooks and scrawled on their backpacks “503.” It was the telephone country code for El Salvador, they told him, a mark of pride in their homeland.

To Steven Aguilar, a gang detective for the Los Angeles Police Department, the number carries a different meaning. It represents a “subculture” within MS-13, which espouses a particularly violent philosophy that requires initiates to kill as a show of loyalty, he testified.

Martin Flores, a gang expert called by the defense, scoffed at that idea, pointing to the gang’s numbers in Los Angeles, about 200 members and associates. “We’ve got to have hundreds of murders a week” to keep pace with MS-13’s growth, he said.

But in Aguilar’s telling, this new requirement gave rise to a series of killings committed by groups, most of them carried out in the Angeles National Forest.

::

She may have been Brayan’s closest friend, but she was dating a classmate and MS-13 associate, Oscar Mendez. At 16, she had given birth to Oscar’s son, and in time, they would have another child together.

Six days before Brayan would die, she’d spoken on the phone with several MS-13 members. She testified that a voice belonging to someone she hadn’t met, someone known as El Desquiciado — the Deranged — told her they wanted Brayan lured to a park “because they wanted to kill him.”

His real name, which wasn’t known to the girl, was Roberto Carlos Mendez Cruz. Mendez Cruz, whose attorney declined to comment, has pleaded not guilty to racketeering and murder.

She and Oscar Mendez took the bus after school to Lake Balboa Park. A slender young man, nearly six feet tall and six years older than the high schoolers, was waiting. El Desquiciado was introduced as “the boss,” she recalled. He led them through the park, explaining “where we were going to be walking to, where I was supposed to take him,” she testified.

Afterward, with Oscar Mendez watching, she sent Brayan a Facebook message that set in motion their trip to the park: “We should go smoke on Monday.”

“OK,” Brayan said.

::

On Oct. 30, 2017, after Brayan and the two girls ditched class, they boarded a bus to Lake Balboa Park. When he wasn’t looking, his friend whispered to the other girl: “Lo van darle abajo.” They’re going to put him down.

Who, she asked.

“Brayan.”

At the park, Brayan and the girls found a quiet spot, where a bike path ducked beneath Balboa Boulevard, and started smoking. Afternoon gave way to evening. They had burned through everything they’d brought when they noticed a teenager walking toward them, making hand signs.

Brayan flashed the same signs back. They were 18th Street signs, and the girls were confused. Unlike Brayan, they knew who he was: Gerardo Alvarado, a former Panorama High student known as “Tato.” Alvarado was 18 and, unlike most of the Panorama High kids who just associated with the gang, was a full-fledged member of MS-13, a detective testified.

Alvarado, now 21, has pleaded not guilty to racketeering and murder. His attorney declined to comment.

He greeted Brayan and the girls, passed out cigarettes and suggested they go to the mountains with his friends to smoke more weed, Brayan’s friend testified.

The four of them piled into the backseat of a dark-colored sedan. It was growing dark, and the girls testified that they could not make out the faces of the driver or of the young man in the passenger seat. Nor, they said, did Alvarado introduce them.

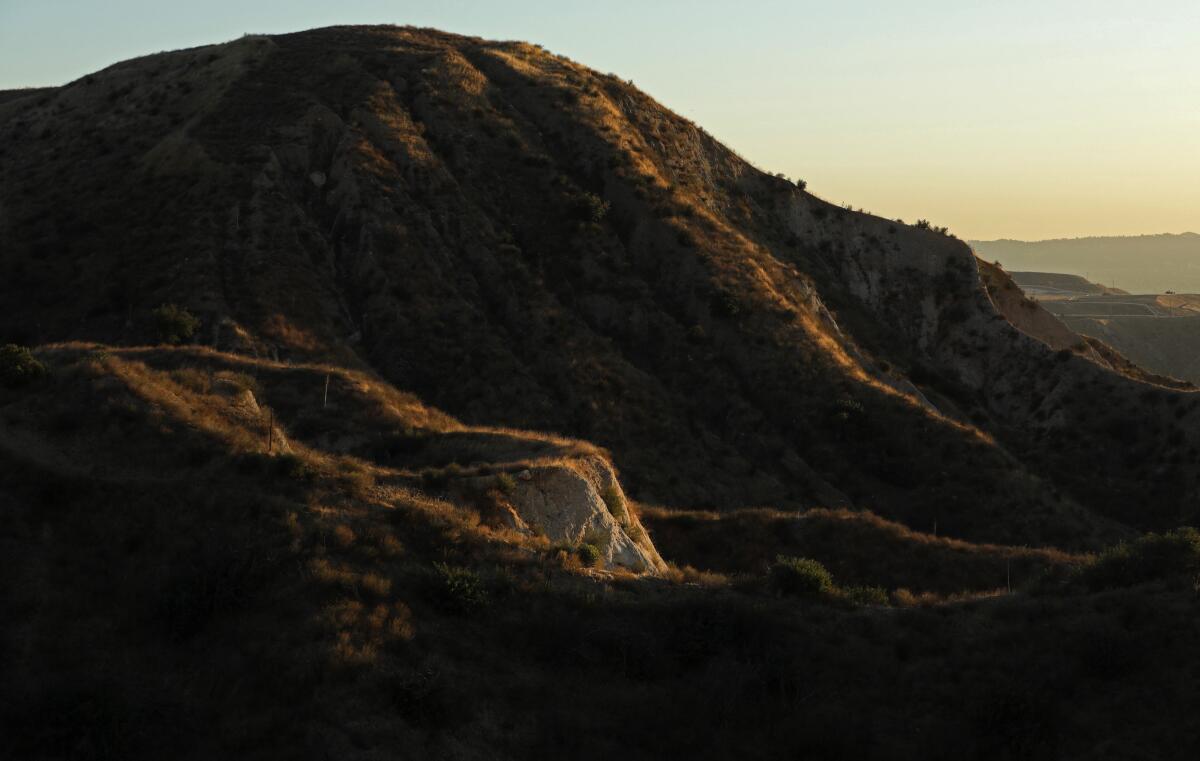

They headed north, climbing a winding road to a clearing in the mountains above Sylmar. Scattered about it were the remnants of a stable: rusted troughs, a skeleton of metal pipes that once supported the structure’s walls, a concrete platform that faced west, toward the Santa Susana Mountains. The sun had sunk behind them, and from the platform, Brayan’s friend testified, they could see the San Fernando Valley sprawled before them, the lights of so many homes and street lamps glittering in the night.

Then, she recalled, Alvarado cut in: “Let’s go walking so we can smoke.”

They scrambled down a narrow trail. Brayan helped his friend keep her footing, while Alvarado pawed at the other girl’s rear, the friend testified. Brayan told him to knock it off.

Suddenly, a boy emerged from brush lining the path, startling the girls. Everyone laughed. As they continued down the trail, more boys — or maybe some were young men, it was difficult to tell — materialized out of the dark, the girls said in court.

Brayan’s friend testified that she recognized two of their classmates, as well as Mendez Cruz — El Desquiciado. After walking for some time, Brayan sat down on the path and announced that he wouldn’t go any farther. El Desquiciado approached Brayan and asked if he knew who he was.

“I don’t know who you are,” Brayan replied, according to the girls. He laughed, clearly still feeling the marijuana. “And I don’t care.”

At this, El Desquiciado struck Brayan in the face and a boy grabbed him from behind, the friend testified. She said she heard Alvarado say he was “hungry and going to kill the chicken.”

The other girl grabbed her by the shirt and they turned to leave. Her last image of Brayan was of him surrounded, trying to fight off the dark figures clinging to his legs, his arms, his back.

::

When Brayan didn’t come home, his mother logged into his Facebook account and read the messages that discussed leaving school for the park. She sent his friend a message, asking where Brayan was. No reply. A week later, a pair of detectives went looking for the girl.

David Holmes and Daryn Dupree, from the Los Angeles Police Department’s Robbery-Homicide Division, were investigating Brayan’s disappearance as a missing persons case. They took his friend to the Van Nuys police station, where she rattled off a cover story about where she was the night he disappeared. The detectives gave her their cards, asked her to call if she heard anything about Brayan, and let her go.

Two days later, Holmes and Dupree interviewed the other girl present at Brayan’s killing. She took them to Lake Balboa Park, then to a ravine in Lopez Canyon, where she tried to pinpoint the last place she saw the boy. The detectives found nothing in the ravine, which was covered in thick brush. They returned a month later. Again, nothing.

The next day, the Creek fire swept through the canyon. With the mountainsides now blackened and bare, the detectives returned to the canyon. Near the foot of a 30-foot cliff, Holmes and Dupree found a charred, twisted skeleton.

::

In a way, Brayan’s murder put an end to the MS-13 clique at Panorama High. Several of them stopped going to school. Phillippi, the campus policeman, testified that the principal called him into his office a month after Brayan’s remains were found and asked: “Officer Phillippi, who do I need to get out of this school to calm this MS problem?”

Alfonso Garcia, Phillippi told him. The boy was gone within days, transferred to James Monroe High School in North Hills, the officer testified. A spokeswoman for the Los Angeles Unified School District said the principal of Panorama High wasn’t available for an interview.

The morning of Feb. 8, 2018, Phillippi took Garcia into custody at his new school, one of eight arrests made that day in connection with Brayan’s death. When the police detained Alvarado, they also searched his family’s Panorama City apartment; in a backpack, an officer testified, they found a numbered list of rules, handwritten in Spanish on a sheet of notebook paper, including one that forbade dismembering bodies within gang territory.

Alvarado, Mendez Cruz (El Desquiciado) and 20 more young men are charged in federal court with racketeering and murder. Brayan’s killing is but one in a series of killings attributed by federal authorities to MS-13’s Fulton clique. An indictment describes in clinical language how the lives of several boys and young men, identified in the document only by their initials, ended in the Angeles National Forest:

“… repeatedly struck G.B. with a machete.”

“… hit E.H. in the chest while yelling, ‘La Mara!’”

“… carved out J.S.’s heart.”

“… lured B.A. to Lake Balboa Park.”

Brayan’s best friend was arrested that same February morning and charged with murder. She would testify that two classmates, Alfonso Garcia and Douglas Rodriguez, were among the boys she recognized in the mountains. Rodriguez and Garcia, both 16 at the time of the killing, have pleaded not guilty in juvenile court to murder.

At Mendez’s trial, the girl was escorted into court wearing the gray sweatshirt, black sweatpants and Velcro shoes issued to every teenager detained in juvenile hall. Mendez, the father of her two children, sat across from her at the defense table. He had grown a wispy mustache and goatee, but his stature remained childlike, his cheeks still plump.

Although he never traveled to the mountains the night Brayan died, Mendez was convicted of murder and gang conspiracy for his role in plotting and coordinating the killing.

He listened to his onetime girlfriend narrate Brayan’s murder — to which she has pleaded guilty — in a flat, low voice. She described Mendez as “the father of my children, but he’s nothing more than that.” His attorney asked: “Once upon a time, you loved him?”

“Yes,” she said, and she began to cry. A prosecutor asked if she had been thinking of Mendez.

No, she said. She was thinking of Brayan.

“The truth is,” she said, “I didn’t want to do that. It wasn’t my intention. But I didn’t have any other option.” She didn’t say anything more, and it was the closest thing she offered to an explanation.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.