Churches shut down by coronavirus offer refuge to immigrants released from detention

- Share via

Before Tsegai fled Eritrea and made the months-long journey to the United States to seek asylum, his image of this country was colored by what he’d seen on TV.

America, he thought, was the kind of place where people could be welcomed in with nothing and manage to turn their lives around.

But when the 30-year-old arrived last year on Christmas Day, officials cuffed his wrists and ankles and led him to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility, where he spent eight months detained. Tsegai asked The Times to identify him only by his first name out of fear of persecution.

“I didn’t expect it, so it was a very terrifying experience,” he said through an interpreter.

A nonprofit paid Tsegai’s $25,000 bond and on Sept. 8, he was released from the Adelanto ICE Processing Facility and moved into an Episcopal church two hours east of Los Angeles.

“Now that I am out of the ICE facility, I can see the true America that I had envisioned,” he said. “There’s so much kindness, there’s so much good outside of the ICE facility.”

Tsegai is one of a growing number of immigrants across the country finding temporary refuge in houses of worship rendered empty by the coronavirus pandemic, after being released from detention facilities.

It’s the latest iteration of the sanctuary movement, which began in the 1980s as U.S. church leaders responded to the plight of Central Americans seeking political asylum during the civil wars that wracked the region.

With President Trump’s election and subsequent hardline enforcement of illegal immigration, congregations again have mobilized to shield those they felt deserved to stay. ICE has a long-standing policy of generally avoiding enforcement activities at “sensitive locations” including churches.

The Trump administration has said that, if reelected, he would double down on immigration restrictions, limiting asylum grants, punishing sanctuary cities and expanding the so-called travel ban. Alternatively, former Vice President Joe Biden has vowed to dismantle Trump’s sweeping changes.

The most recent twist varies from traditional political sanctuary, in which some people remain on church property for months or years to avoid arrest by ICE. The COVID-19 pandemic has added urgency to offering shelter to immigrants.

More than 7,000 detainees have tested positive for the coronavirus across the country, according to ICE, and eight have died of COVID-19. With outbreaks infecting hundreds at some facilities, including 242 at Adelanto, immigrant advocates have mobilized to seek the release of as many as possible.

In response to federal lawsuits in California, judges have compelled the release of hundreds of immigrants at the state’s five ICE facilities to permit space for social distancing, quarantine and isolation. In one scathing order last month, U.S. District Judge Terry Hatter accused federal officials of “straight up dishonesty” while directing ICE to reduce the population at Adelanto by more than one-third.

Other detainees have been released on bond pending the outcome of their cases in immigration court.

California isn’t the only place where churches have stepped up. Congregations in states such as Texas, and the region including Maryland, Virginia and Washington, D.C., are sheltering immigrants released from detention, said Myrna Orozco at Church World Service, which works with and tracks the sanctuary movement.

“The sanctuary movement definitely paved the way for congregations to be creative in how they offer welcome to folks,” Orozco said. With detention centers still flaring up as COVID-19 hotspots, she said, “hopefully this will continue to increase as people are released.”

Before they can be released from detention, immigrants must provide the address of a legal sponsor to federal officials. For many, it’s the address of a relative or friend. But some, like Tsegai, arrive knowing no one.

In an organized resistance to Trump’s policies, hundreds of people had once pledged to open their homes to immigrants being released from detention centers. But the pandemic has forced many families to tighten their social circles, cutting off a key source of transitional housing.

That leaves congregations such as Heritage United Methodist Church in South Los Angeles to fill the gap. Lead pastor the Rev. Ivan Sevillano said he understands intimately the plight of immigrants: He lived for 10 years without legal status after overstaying his visa from Peru.

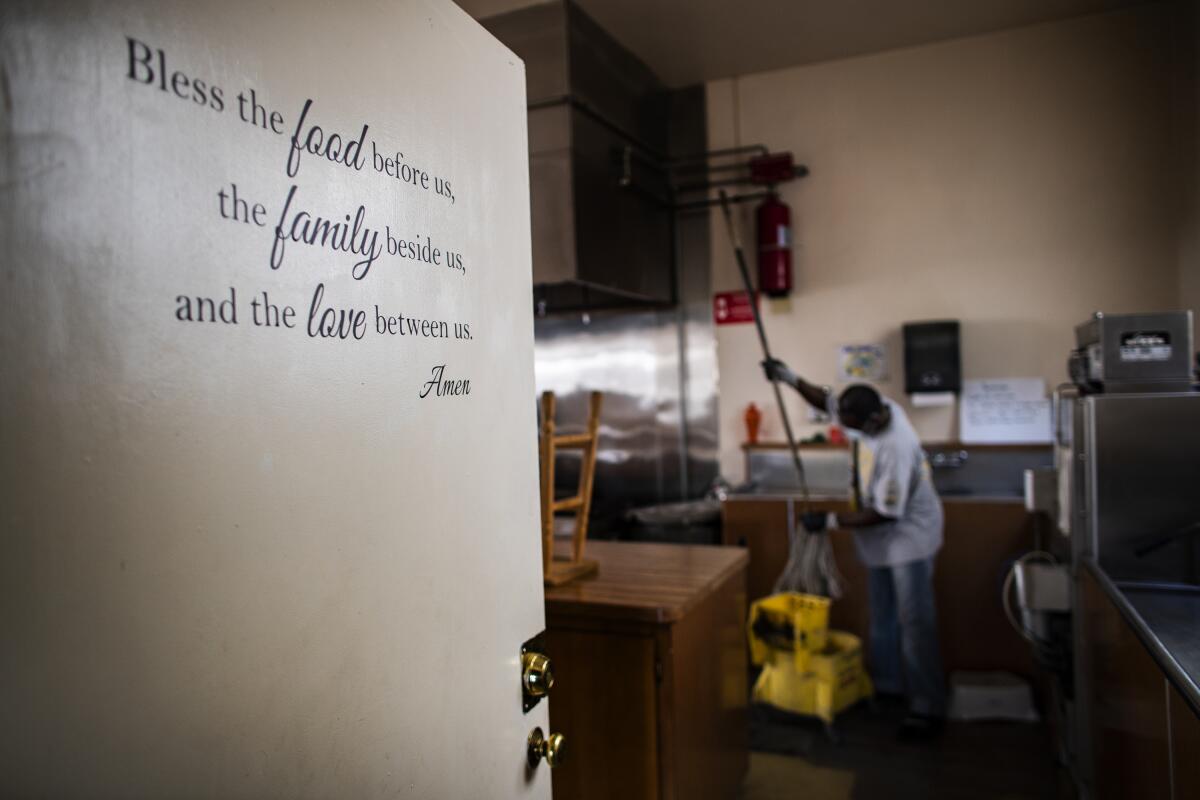

Heritage, a historically Black church dating to the 1880s, has long served the surrounding homeless community, offering people Sunday breakfast, showers and the ability to park in the church lot. Its 15-member leadership board voted last summer to begin taking in immigrants released from detention centers.

“Though we don’t open for services, always throughout the week we are doing something for someone,” Sevillano said. “Many of us Christians preach but don’t act. The important thing is also to act because there are people out there that need help.”

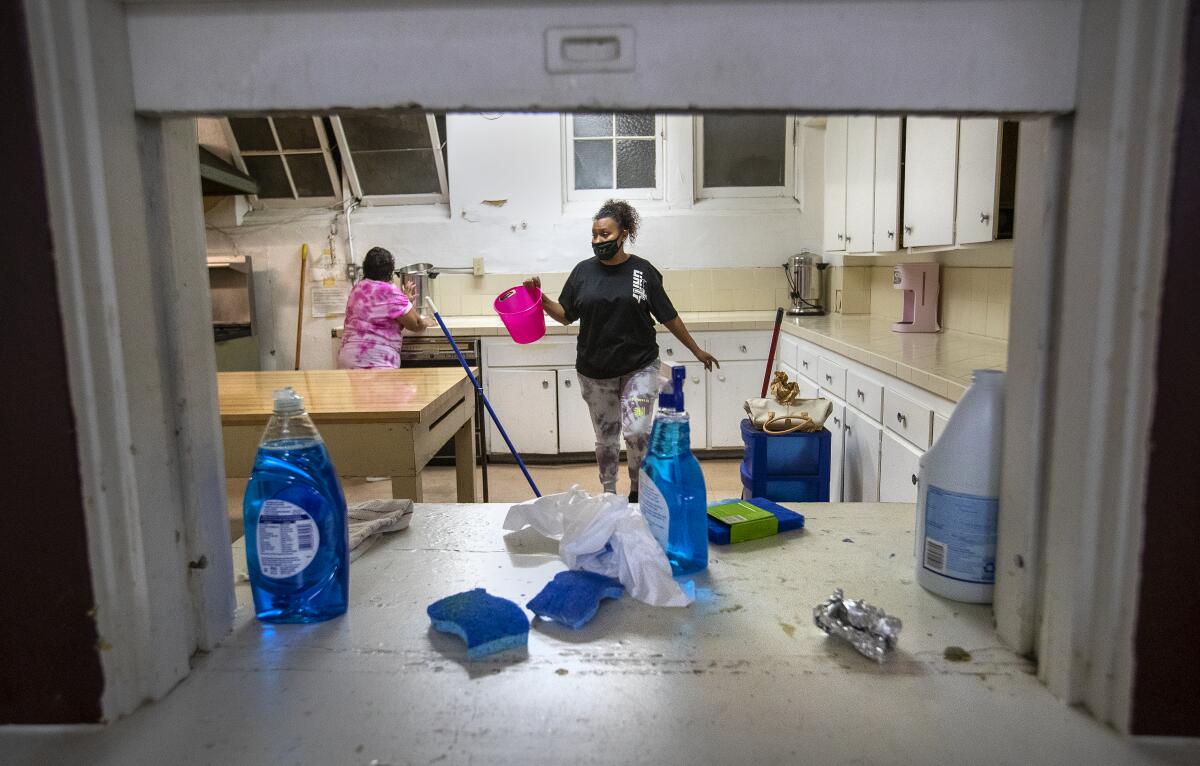

On a sunny Thursday afternoon in the Heritage parking lot, Guillermo Torres, immigration program director at the nonprofit Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice, led three women to his Subaru Outback. From the trunk, they pulled brooms, a mop and buckets with Pine Sol, bleach and Windex.

They set to work converting the church’s dusty basement into a home for released detainees. The space, which includes a large community room with a piano and foosball table, an industrial kitchen and a classroom, hadn’t been utilized in years.

A leak in the kitchen sink would need fixing and some of the countertop tiles were cracked and loose, but the microwave and blender worked and the cupboards were stocked with cookware, dishes and utensils. The classroom, which was piled with old chair desks, couches and sheet music, would soon be transformed into a bedroom with five beds and soft yellow walls.

Members of Nikkei Progressives, a Japanese American community organization, dropped off boxes of shirts, shoes and backpacks stuffed with toiletries.

Torres led them on a tour of the church and unfinished living space. CLUE has coordinated with six churches in the greater L.A. area willing to take in immigrants, he said. Others have offered help with donations, food and logistics.

Torres said the effort shows there are more humane alternatives to detention. It also paints faith communities in a positive light, he said, particularly during a time when some have been shown to dehumanize immigrants and other vulnerable populations.

“This shows the true meaning of religion,” he said. “This gives a lifeline to people that otherwise would not have a lifeline.”

With no foreseeable end to COVID-19, Torres expects more detainees to need housing as they are released from detention.

Back at the Episcopal church in San Bernardino County, Tsegai starts his mornings with a prayer. A Christian and an ethnic minority in Eritrea, he said he was falsely accused of criticizing the government. After surviving four years in prison labor camp, he escaped, leaving his mother and six children behind.

A different type of danger befell him in ICE custody. At the Adelanto facility, Tsegai and the other detaintsees stayed glued to the TV, watching updates about the spread of COVID-19.

“I didn’t think I’d get out of there alive,” he said.

Tsegai’s days are significantly quieter than before. He goes on long walks around the neighborhood. He cooks meals for himself — cubed beef with berbere seasoning or in a spicy tomato sauce. He spends time talking to his children, who call frequently to ask when he’s coming back.

He can’t give them an answer. But for now, at least, he is savoring the new sense of freedom and safety, relishing the simplest pleasures. “I have a room of my own. I have plenty of food. I can move around.”

Interpreter Zion Yohannes contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.