Going home: The American dream lives in the barrio

- Share via

It is a ritual observed nearly every day. The mail carrier approaches the small cluster of hillside barrio homes in East Los Angeles, armed with spray repellent in case one of his antagonists gets too close. The neighborhood dogs, sensing the moment, spring to the ready.

Just as he approaches one mailbox, a pack of dogs, separated from the mail carrier by a chain-link fence, lets go a chorus of howls that alerts all other canines in the area.

The mail carrier quickly deposits his cargo and steps back to his Jeep. No matter, the dogs keep up the yelping. The roosters and chickens in coops on the hills overlooking this noisy scene crow their presence.

As the mail carrier wheels his vehicle for a getaway, one dog scales the fence and gives chase. The howling now seems to drown out the musica Mexicana drifting from the windows of the small homes.

Moments later, the mail carrier is gone. The dog that gave chase nonchalantly returns to his resting place. Mission accomplished; ritual observed.

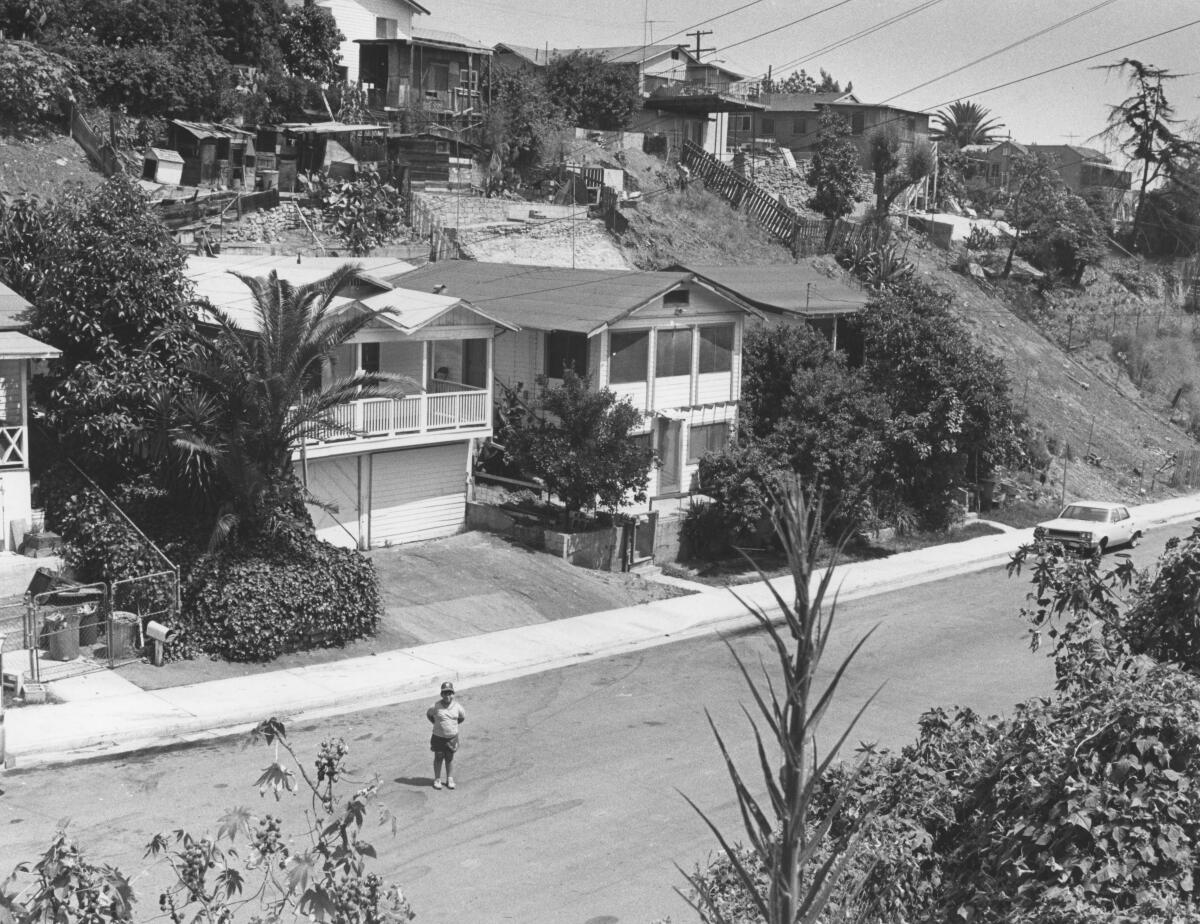

Welcome to the world of 812 N. Record Ave.

::

After 18 years, I went to 812 N. Record Ave., to the house where I once lived, to the Belvedere Gardens barrio where I grew up.

My barrio is unique in this megalopolis that is Los Angeles, an obscure corner of an affluent society, a place seldom visited by progress. For example, sidewalks and curbs were installed only recently. English is heard only occasionally.

Downtown Los Angeles is only 4 ½ miles away, but there is no hint that shiny skyscrapers are just over the horizon. Some neighborhood businesses on Hammel Street, near Record, have deteriorated beyond hope. Dogs, chickens, cars under constant repair, graffiti, homes valued under $35,000 and neighborhood tortillerias are fixtures in the landscape.

Nestled in a rural-like setting, yet ringed by three urban freeways (San Bernardino, Pomona and Santa Ana), Record is a quiet, out-of-the-way street north of Brooklyn Avenue that trails off in the surrounding hills of another East Los Angeles barrio, City Terrace.

The inhabitants of Record are poor but proud people, comfortable in the knowledge that they own their homes and owe little to an Anglo-dominated society. To them, life on Record is as American as that in Kansas, and hopes are resilient as tall wheat in a summer breeze.

No one really knows what to expect when he goes back to the old neighborhood.

I remember rampaging on the surrounding hills, building cabins out of abandoned furniture, auto doors and bamboo, and killing imaginary enemies with a crudely constructed gun made of clothespins. In an ongoing scenario, one close friend, David Angulo, was Tarzan and his brother Stephen was Cheetah the chimp. I was a hunter—I can’t remember if I ever used the term “Great White Hunter”—always seeking Tarzan’s help.

Now, property owners look after their investments with fences, forcing local jungle warriors to play elsewhere.

There were organized activities for the area’s Chicano youngsters. After-hours softball games at Hammel Street School (Panthers vs. Dragonflies) routinely attracted 40 to 50 youngsters, prompting teachers to let them play all at once. Trying to get a ground ball past two shortstops and three third basemen was hard.

As a Dragonfly, I remember losing one game, 6 to 5, on a disputed call at third base. No amount of intervention by the teachers avoided the game’s real outcome later — two bloody noses for the Panthers and one scraped knee for us.

But Hammel, where actor Anthony Quinn went to school as a boy, is a far different place today. In my time, the early 1950s, boys and girls were segregated on the playground during recess. Baseball cards, tops and yo-yos were confiscated as unauthorized items.

The school’s tough rules extended even to the after-hours softball games. I was once called out simply because I entered the batter’s box before I was told to do so by a teacher.

Youngsters at Hammel were prohibited from speaking Spanish, a common restriction at the time.

Once, a classmate whispered something about a, movie on television that night. I told him in Spanish that I would see it at a cousin’s house. Hearing the chatter, the teacher approached me.

“Not only don’t I like talking in class,” he said, “but I especially don’t like it in Spanish.”

I stood in the corner, back turned to the class, for an hour. The same offense later earned me a shaking—the teacher shook you until he thought all knowledge of Spanish had fallen out of your head.

These days, all office workers at Hammel are bilingual. All the school signs are bilingual.

Charles Lavagnino, Hammel’s outgoing principal, was vice principal when I first entered school there. Lavagnino told me that his fondest years as an administrator were in East Los Angeles.

Looking back, he conceded that he had supported some of the restrictive measures imposed in the early 1950s, mainly to keep a tight rein on unruly students. But improved teaching methods as well as sensitivity to the reality that East Los Angeles is 95% Latino have made Hammel a better school today, Lavagnino told me.

“This is a good school; we try to involve the parents,” he said.

I was reminded of other aspects of life on Record as I revisited old haunts:

—La Providencia, the nearby mom-and-pop corner store, still extends credit to its faithful, my 81-year-old grandmother assures me. The owner trudges up Record with Grandma’s groceries about twice a month.

—The neighborhood church, Our Lady of Guadalupe, still chimes its invitation every morning.

—The vatos locos (crazy street guys) have changed hardly at all. Dressed in cholo-type “uniforms” (khaki pants, flannel shirts and bandanas around the head), they still cruise neighborhood streets in lowered autos and ask passer-by for money. They are distrustful of outsiders and are quick to confront anyone who challenges their “turf rule” of the area.

—Many of the families I remember have remained in the area. A close friend of my mother provided some insight: “Yes, I’d like a nicer home, pero aqui estoy contenta. The kind of people who still live here maybe are not the type of people who want to advance, but here I’m content.”

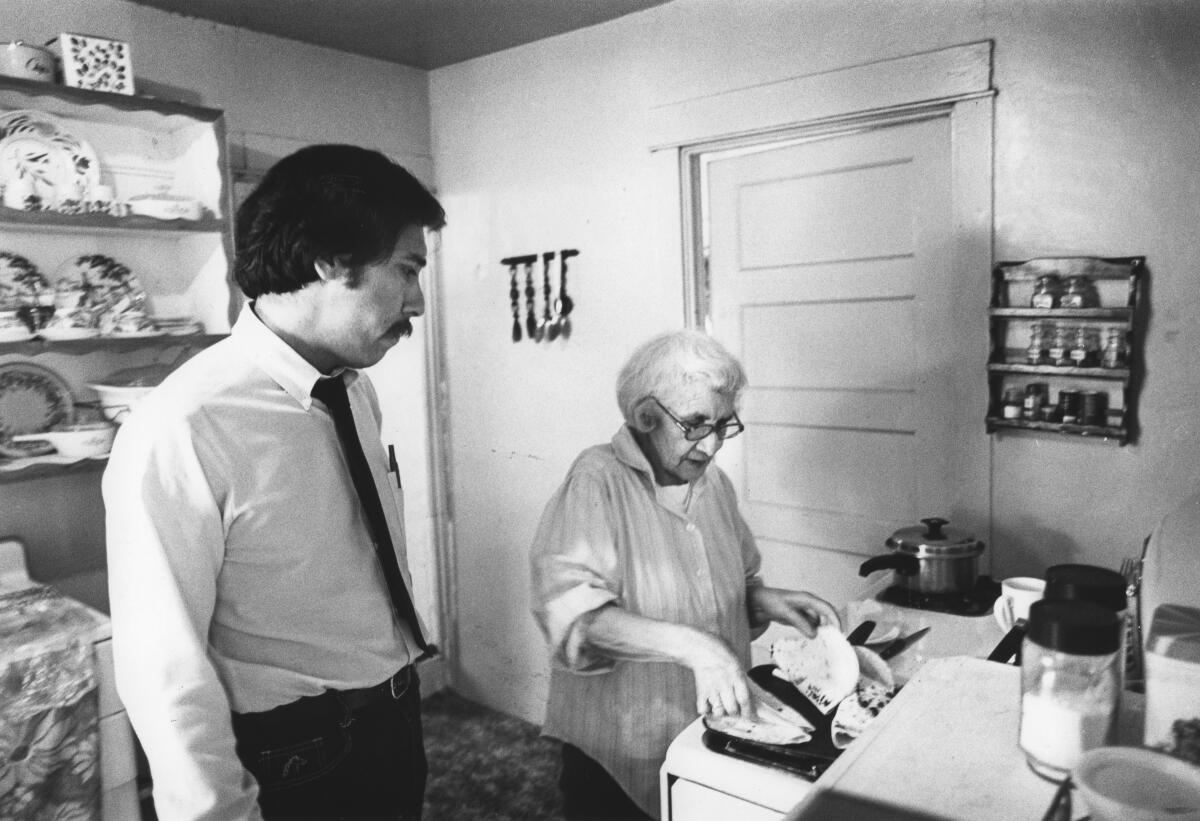

In many ways, life on Record has not really improved that much since my parents bought the small, wood-frame home at 812 for $3,500 from relatives in 1946. But don’t dwell on the negative when you meet my grandmother, the current resident of 812 N. Record.

Living there has given her a freedom she cherishes in old age. No one tells her what to do. She is free to run her life without interference. And there has been no threat to her safety -- neighbors look out for one another, and the dogs herald the arrival of any stranger.

The 530 -square foot house, built during the Depression, is currently assessed at $9,873 and may need a lot of work, but Grandma is an optimist, Soon, she said, a shower to replace the old bathtub will be installed. “And look,” she promised in Spanish. “I’m having new pipes for the plumbing put in.”

Felicitas Ramos, born in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, has a heart that is as loving as it is coy. She is always offering food and is sometimes critical because I am still single, but there are some subjects best not discussed. For one thing, don’t scold her about her oven.

Grandma has this peculiar idea about heating. She’ll turn on the oven and lower the oven door,

“It works fine and I’m comfortable,” she says.

“But it’s dangerous,” I remind her. “Something could happen.”

“How?”

Concerned grandchildren, fearful that the dreaded would occur, purchased an electric blanket. But during last winter’s rains, I noticed that the oven door was still open.

“Oh,” she said, “I’m just drying clothes.” She then draped clothes over the oven door.

“But there would be a fire,” I said.

“How?”

Then she changed the subject: “Want something to eat?

Grandma’s daily routine varies little. There is the music from the Spanish-language radio station KWKW, the morning chat outside with the neighbor (“Can I borrow some eggs?”) and the puttering in her garden.

At midmorning, she will collect clothes for a wash. In the old days, the washing machine was in the bathroom, making it difficult to use the bathroom for most other purposes. Now the washer is in the bedroom. People on Record don’t rely much on dryers. Clotheslines are still in vogue.

Cooking seems to be Grandma’s favorite pastime. Flour tortillas are made from scratch and beans and rice are the backbone of any meal -- beef, eggs, hamburgers or quesadillas. If you’re not ready to eat right away, everything is left warming until you are finally hungry. All meals are accompanied by milk.

By noon it’s time for the soaps.

I’ve never understood how a person with such limited English ability can give a running commentary in Spanish of “Days of Our Lives.” But she does.

“Mira, hay ‘sta el viejito (describing one of the main thugs). Si, el es papa de Jessica, pero ella no lo quiere. (Why doesn’t Jessica like her father, Grandma?) Oh porque el es muy malo con la mama de ella y los pareintes de ella lo saben (And how did Jessica’s relatives find out about this cruelty?) El abuelito trabaja en un hospital y la esposa supo todos los problemas que Jessica tenia con su padre.”

Maybe working in a hospital does give one insight,

Then she pops her favorite question: “Tienes hambre?”

I decide I’m not hungry yet.

By nightfall, it’s time for a movie on Channel 13. Again, Grandma will let me know if I miss anything.

One particular night as the movie unfolded, so did Grandma’s life story, an off-limits topic if there had ever been one.

Born in 1902, she said she hardly knew her parents. When she was 17, my father was born. Six years later she moved to the Mexican border town of Ciudad Juarez across from El Paso to find work There she gave birth to my aunt Hortensia.

She and her two children were on their own when she met a Ft. Bliss soldier, Marcelino Ramos. They were married in a Mexican civil ceremony in 1930, and later repeated their vows in a church in 1933.

In 1936, Marcelino, Grandma and her two offspring came to Los Angeles, settling in an area near 8th and San Mateo streets on the southern edge of downtown, now an industrial area.

Well, things didn’t work out. Marcelino left, the Army was looking for him, he married someone else. (What happened to the divorce, Grandma?) By now her memory seemed to be getting deliberately hazy.

Finally, she concluded with the inevitable, “Are you hungry?”

I finally decided to eat.

::

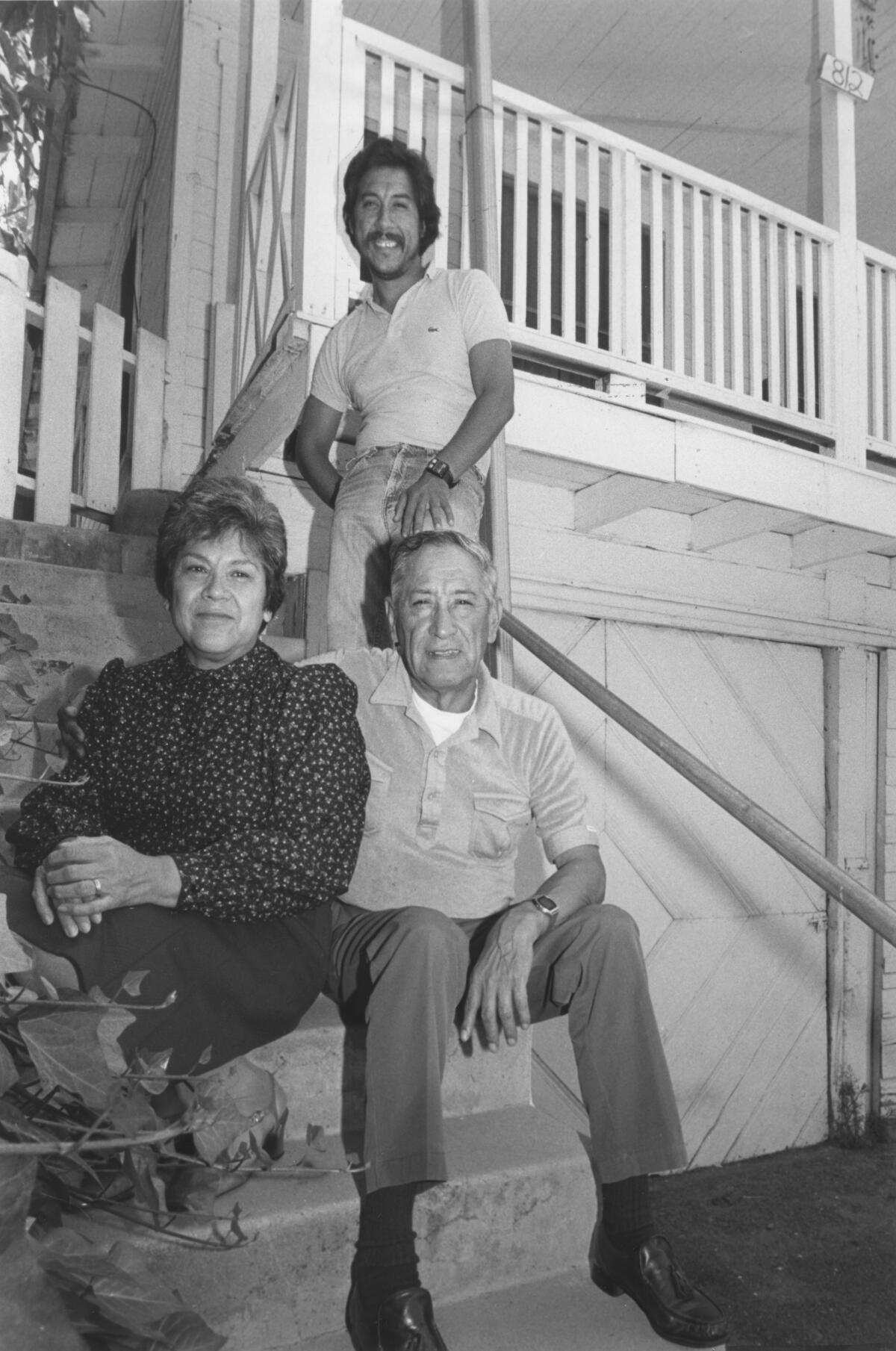

If life at 812 N. Record Ave. is pleasurable for Grandma, then the opposite was true for my parents.

Miguel Antonio Vargas Ramos and Maria Santos Medina were newlyweds when they moved into 812 N. Record Ave. in 1946. The prospect of living there did not excite them at all.

They saw no future in the house for a young family, given the surroundings and the condition of the dwelling. It didn’t come close to the post-World War II housing tracts being built in places like Lakewood.

There was no possibility of expanding the house. It already had been expanded to add the bedroom, bathroom, porch and garage.

There was no door-to-door mail delivery. Mail had been delivered down at the corner of Record and Floral Drive, about 300 yards downhill from our house, since the homes on Record were built.

The same situation existed for trash collection. It had to be hauled down to Record and Floral, no easy task for residents living up the hill where Record trailed off, a distance of about half a mile.

My father, who was employed at the now-abandoned Uniroyal tire plant off the Santa Ana Freeway in Commerce, had tried to find other housing -- the Aliso Village project on the edge of downtown, the Ramona Gardens project near County-USC Medical Center in Lincoln Heights and a Boyle Heights trailer park that eventually gave way to a Times-Mirror press plant.

He made too much money to quality for the subsidized housing, but too little to leave Belvedere Gardens.

“I didn’t like the area (Record),” he said. “I wanted to leave, but we couldn’t do it economically.”

“The area was a dumping ground for everything. You’d wake up in the morning and find a car left there... no tires, no engine... nothing. We had to call the tow truck to haul them away.”

And there were the dogs. Mom hated them:

“I always had to clean up after them. And with you guys (my brother and I) around, I had to be careful. Complain about the dogs? Are you kidding? They (the neighbors) would just ignore you.”

And the mail.

No one seems to know why the mail was dropped off at Record and Floral. Maybe the dogs were as ferocious in the early 1950s as they are now. Probably no one bothered to ask for door-to-door delivery.

But it changed one day when a thief stole a federal income tax refund check from our mailbox. It wasn’t a lot -- “something like $120,” my mother recalled -- but it seemed a lot to us then and its arrival had been anxiously awaited.

With no support from the neighbors, Dad campaigned for door-to-door delivery. It was instituted after a few calls to the right people at the post office.

Mom, in the meantime, began petitioning for trash collection at each home. She too succeeded, but only after a false start. On the first day of the scheduled collections (this was in the early 1950s) the neighbors placed their trash in front of their homes. The garbage men never came.

“There I was with egg on my face,” my mother recalled.

“So I called again and sure enough the next week they came (to collect the trash). They have been doing that ever since.”

Mom even joined the PTA at Hammel Street School, becoming PTA president in 1954. Every time I got into trouble, I was reminded of my mother’s good work on the PTA.

Now, when I look back I realize that life was tough on Record. But it didn’t seem so at the time.

Yes, my yard was too small to play in, but my ragtag gang of friends considered the streets and hills our playground.

Yes, the house was too small for a growing family, but it seemed adequate to me and I remember how proud my mother was of the new furniture that was bought for the house. (There was no eating allowed in the living room, Mom decreed. Grandma was more lax about such things.)

Dogs? Well, we stayed out of their way. But if someone was challenged to a rock-throwing contest, the dogs turned out to be handy targets. Now, the main objective seems to be to separate neighborhood dogs from other canines and the mail carriers.

In 1957, my parents finally realized their dream of getting out of East Los Angeles. The found a small tract home for $12,900 in Downey.

Grandma then moved into our home on Record, but I continued to spend a lot of time there until I went to college because I felt strange in our new environment.

My parents were excited by this new beginning in Downey. It was the end of their rainbow. I thought I should be excited too, but I wasn’t sure. I wondered how I would fit in the neighborhood where there were very few brown faces.

An indication of why I had doubts about life beyond Record was as rude as it was puzzling. A classmate called me a nigger.

The term was unheard of on Record.

::

George Juarez was one of the neighborhood kids I grew up with. He was a street-wise guy who seemed to know a lot. And showed it. But the years have not been kind to George.

He is a victim of the Eastside’s street-gang reality. The facts seem hazy; the neighbors, as well as Grandma occasionally whisper about it.

But it seems that George, now 41, was with some friends who brawled with other Eastside youths in a rather ugly incident back in 1961. George was run over by a car and left for dead. He recovered from some of his injuries after time at County-USA Medical Center and two years of rehabilitation at Rancho Los Amigos Hospital in Downey.

But a brief conversation with George these days betrays his pain. One leg is damaged, and he needs the help of railing to get up the stairs of his home, where he lives with a brother and his mother. His speech is slurred and his memory is hazy -- he still asks about my brother Michael who died in 1954.

“Pues ya ‘stuvo, Georgie old boy,” he says in Eastside street lingo. “I dropped a few pills, drank a lot of hard stuff ... y pues era muy loco.”

“Ahora, I know better. My leg hurts a lot. I drink a little beer, but that’s about it.”

Several other guys on Record have had run-ins with the law. One neighborhood guy had drug problems after he returned from military service in Korea. Several of my friends joined the local street gang, Geraghty Loma (named after the hill that Geraghty Avenue winds around), and sheriff’s deputies paid occasional visits to unsuspecting parents, who insisted that their sons were good boys in school.

Another companion and I were friends with a rival street gang, Los Hazards (named after nearby Hazard Avenue). The conflict occasionally meant defending oneself with more than fists. Two friends from Record who were part of that conflict eventually became part of California’s burgeoning penal system.

But for every problem kid, there is a success story.

Two brothers on nearby Herbert Street, for example, have done well by neighborhood standards; one is a career soldier and the other is a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy,

And one resident became a reporter.

Some in the area are alarmed at the street-gang violence and say they won’t go out at night, Others bristle at the suggestion that the area is unsafe, Raquel, one of George Juarez’s sisters, is eloquent in the street-wise vocabulary that is Record Avenue.

“I tell people I’m from East L.A. And they tell me, ‘Wow, man, you must have been chola. Or you’re my homegirl.’ I’m no I come from a good area. I went to school there.

“I live in Whittier now and I wouldn’t have any problems if my kids went to school here.”

::

I have often wondered what will happen to Record Avenue. Will its rural ambiance remain? Will Record still be an obscure corner of society in 20 years?

I don’t know all the answers. But of this I am certain.

Spanish will still be the neighborhood language, but the dogs won’t always heed it.

Grandmothers like mine will still be there. Life’s many chores will be done as they always have been, haphazardly on occasion and other times with meticulous care.

A family’s success will not be measured by how much money it earns. It will be evident in the accomplishments of its young.

Record still will nurture dreams of young families for a better life, as well as hold old families to an area where they have grown comfortable.

For those of us who lived there, the world of 812 N. Record Ave. will never be obscure. It will never die.

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.