Spanish-language newsstand, a 1940s Boyle Heights gem, braces for the end

- Share via

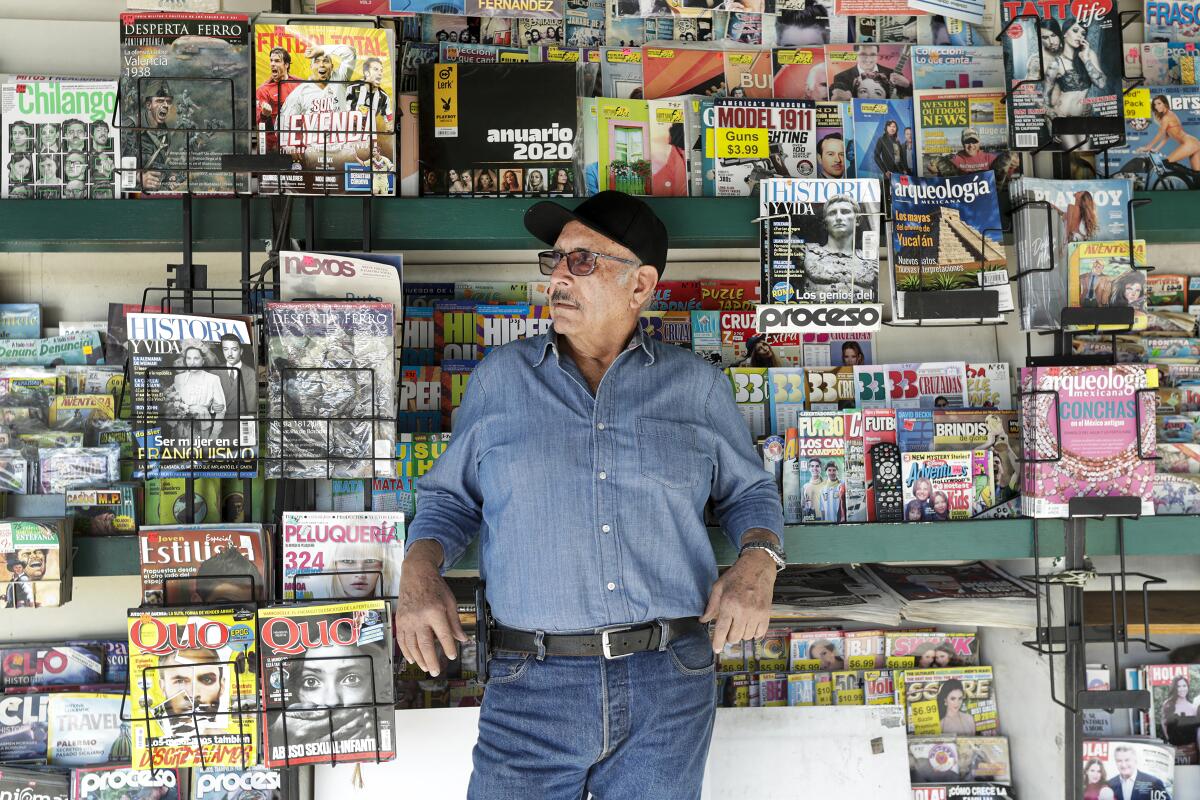

Rafael Ramos stood at his Boyle Heights newsstand on a sunny morning. Above, a faded green awning proclaimed: ALL KINDS OF SPANISH MAGAZINES AND NEWSPAPERS.

Over the buzz of traffic at the corner of 1st and Soto streets, he chatted with his lone employee. Pedestrians walked past the newsstand, crossing the street toward the Metro Gold Line station. Hours could go by without a sale, so Ramos mostly waited.

Margarita Chipres walked up and thumbed through a copy of TV Notas, a gossip magazine about Latino celebrities. The 75-year-old likes to know the world’s chisme, she said. But even if she was one of Ramos’ regulars, she wasn’t going to spend a dime.

“They don’t want to give me a magazine,” Chipres said, feigning disappointment before strolling away.

“These are my clients. Puros quinceañeros,” Ramos joked with bemused resignation. Just young folks.

The 71-year-old Highland Park resident has owned the newsstand for 25 years, but like the rest of the publishing business, it’s been hit hard by a digital revolution that has seduced the eyes of the young away from print. Ramos’ customers are almost entirely elderly immigrants. For their children or their children’s children, the pages of Mexican news publications such as La Jornada and Proceso or Spanish-language gossip magazines hold little allure.

Growing up American, they were as likely to listen to Nirvana as they were Los Tigres del Norte, let alone pay to read what their immigrant elders read. By any metric, especially in an old Los Angeles neighborhood that skewed toward a younger demographic, that was bad news.

By Ramos’ reckoning, he is destined to close shop before the year ends.

“We tell people we’re going to close and they say, ‘How could you close?’” he said. “Basically without earnings, we’re open just to be there. You can’t live off the newsstand business anymore.”

In the late 1940s, the newsstand opened at this very intersection. Several people have owned it over the generations — years during which Boyle Heights went from a true polyglot melting pot of Mexican, Jewish, Italian, Eastern European, Japanese and other people to one of L.A.’s capitals of Mexican American culture.

Then, and for decades after, reading newspapers was the main way people of all stripes got the news — a reality captured in many a Hollywood movie in which scenes often featured a protagonist (think Michael Corleone finding out his father has been shot in “The Godfather”) leafing through their pages in grim discovery.

Long before he bought it, Ramos was a mechanic from Highland Park perusing the pages of the newsstand’s wares. Then, one day, the owner made Ramos an offer he, apparently, couldn’t refuse.

“‘Come on, buy it!’” the man told him. “‘It hasn’t made me rich, but it’s a job like any other, to live.’”

Ramos had grown tired of the physical strain of his work as a mechanic. He felt the creep of age and thought he could make a go of the newspaper business.

“So, he convinced me, and I bought it,” Ramos said.

In the beginning, business was good. Every day, he’d sell up to 40 copies of the Spanish-language newspaper La Opinión. Now he stocks just 10 and will sell four or five in a day, Ramos said. Dozens of copies of the Los Angeles Times — one of the few English-only offerings — would once fly away in a day. Now, maybe one or two.

The worst tragedies seemed to bring the most customers to his stand: when Luis Donaldo Colosio, a Mexican presidential candidate, was assassinated at a campaign rally in Tijuana; when superstar entertainer Jenni Rivera was killed in a plane crash; when the singer Selena was shot to death by one of her employees.

“You’re there, surrounded by the day’s news as people are learning everything,” he said. “You know about everything. The news at your fingertips.”

Ramos’ newsstand remains one of the largest in L.A. with the greatest variety of Spanish-language offerings, he said.

Besides Mexican newspapers and other Spanish-language publications are some random finds: a Rolling Stone magazine tucked behind an illustrated novela featuring a blond man and woman locked in a romantic embrace. There’s Playboy en Español sitting atop a food magazine. Next to a magazine devoted to the late Mexican singer José José hangs a health magazine titled Para Adoloridos, Vol. 2. (For those with aches and pains, Volume 2.)

These are the publications that have survived the great print bloodletting. Many more succumbed a long time ago. Every so often, someone will ask for Alarma, a gory tabloid about crime in Mexico that featured a crossword puzzle with a scantily clad woman amid the hyper-graphic carnage.

Thursday mornings are the newsstand’s busiest time. On a recent one, Humberto Gomez, 72, sat on a folding chair at its edge, quietly reading through a novela from the classic “El Libro Vaquero” series, which told tales about the Old West.

As he flipped through the pages, Gomez envisioned cowboys riding through vast deserts.

“I love reading to entertain the mind and not think about negative things,” he said. “It keeps your mind working.”

For Gomez, the pulpy stories in the novelas felt like an antidote to the depressing news on TV. He couldn’t stand to watch or hear or read any more about the helicopter crash that killed Lakers great Kobe Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter Gianna and seven other people. The newsstand was an escape. Gomez said his novela habit started as a boy; it was an inheritance from his father. Now he comes here to read almost daily.

“They even have a little chair for me,” he said.

Here, the retired cab driver meets friends like Chipres, the regular visitor and, sometimes, paying customer.

Years ago, when the mother of six sometimes needed help to get to the grocery store, she counted on Gomez to be her ride. He’d wait outside the store and help her unload her bags. That’s service most other taxi drivers won’t offer, Gomez boasted.

Their lives have slowed down and they don’t get around like they used to, but they still see each other,from time to time, at Ramos’ stand.

On this Thursday, Chipres returned after she left without buying.

“I don’t mark the date. I don’t have a schedule,” Chipres said. “I always pass by here and I entertain myself. We get angry and pull each other’s hair out.”

For the second time, she left without making a purchase.

The newsstand’s sole employee, 61-year-old Gerardo Campos, sits or stands near the cash register beneath a sign that reads: “Open Thursday through Tuesday from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.”

Unlike Ramos, Campos is not much for chitchat. When he makes a sale, he wordlessly exchanges money. He shuffles from one end of the newsstand to the other, occasionally unfolding a short ladder to rearrange the magazines above him. Sometimes, he makes the smallest of small talk with the regulars. He thinks about his looming retirement, in March.

Ramos is the owner of the newsstand, but Campos is its keeper. He keeps all of its modest earnings. That usually amounts to a few hundred dollars — on a good month. Ramos sees the stand as a way to help his friend, Campos, make a few bucks. But Campos doesn’t see a point in continuing to mind a stand the way things are going.

“This is going downhill now,” Campos said. “This is all going to be over soon.”

The newsstand has survived this long partly because of people like 82-year-old Carlos Bacelis, who delivers Mexican publications to stands across L.A. that have a heavily working-class and immigrant population.

Bacelis travels from his home in El Monte to Tijuana, where he picks up stacks of Spanish-language newspapers and magazines, some from Mexico City. On most Thursdays, Bacelis makes the drive back up to Los Angeles, stopping at 1st and Soto, and a handful of other stands: two in downtown, one at Pico and Western, and one at 7th and Alvarado.

He started the gig in the 1980s, when he got a job delivering newspapers for a publishing company called AmerMex. When that company shut down, he kept delivering.

“I do it as a distraction, so I’m not at home watching TV all day,” Bacelis said. “My clients are my friends. I sit and chat with them, and sometimes we have lunch.”

Over the years, his clientele has shrunk. As he drove around L.A. in his truck, Bacelis saw stands that had shut down one by one: in San Fernando; in Van Nuys; in Pacoima, Encino and Hollywood.

“Everything has its time,” he said. “Everything begins and everything ends.”

Ramos does not shy away from that reality. From his corner stand, he has watched Boyle Heights change. But he doesn’t see anything on the horizon that will change things for the better for his business.

Maybe someone will come around and maybe Ramos will persuade them to take this gamble at 1st and Soto. But Ramos would be considerably less sanguine than the man who sold him on the newsstand dream so many years ago.

“I’d be honest and say, ‘Look, you won’t earn a living here,’” he said. “I don’t know what’ll happen.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.