L.A. fast-food workers may get a helping hand from City Council

- Share via

Fast-food workers have long complained of unstable schedules that make it difficult to plan their finances, child care, medical appointments and other obligations.

Now, a proposal by Los Angeles City Councilmember Hugo Soto-Martinez aims to give these workers more stability and consistency in scheduling, as well as access to paid time off.

The proposal, which Soto-Martinez plans to introduce as a motion Tuesday, seeks to expand the reach of the city’s Fair Work Week law — which requires that employers give retail workers their schedules in advance — to include some 2,500 large chain fast-food restaurants that employ roughly 50,000 workers.

It also proposes an annual mandatory six-hour paid training to help educate workers on their rights. And it would require that fast-food workers accrue an hour of paid time off for every 30 hours they work — on top of paid sick leave to which they are already entitled.

The push is the latest move by lawmakers across the state to improve working conditions for low-wage fast food workers who’ve struggled to make ends meet in expensive cities such as Los Angeles. Earlier this year, California adopted a minimum wage for fast-food workers of $20 an hour.

With the state’s mandatory minimum wage for fast-food workers set to increase to $20 an hour, many restaurant chains are preparing to raise prices.

But the proposed city ordinance is likely to be met with stiff opposition from industry groups.

Several business and trade groups have said that this type of predictable scheduling policy complicates the process of scheduling staff.

The Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce had said that a similar L.A. County measure would hamper businesses already struggling to compete against e-commerce companies. And the California Grocers Assn. said it would make last-minute staffing changes “extremely challenging.”

Soto-Martinez said the idea behind the L.A. measure is to give fast-food workers the financial ability to attend a wedding, a quinceañera, a doctor’s appointment, or their child’s graduation — entitlements of many white-collar workers.

“Fast-food workers, their needs and their desires, are often ignored. We need to do our part as a city,” he said.

A coalition of industry groups led by the International Franchise Assn. said Tuesday that the proposed regulation would burden small-business owners with costly new requirements at a time when they are already struggling with the recent wage hike.

“I cut back on employee hours by 10%, and I’ve been forced to raise prices to cope with the state minimum wage increase. I can’t absorb any more costs,” said Behzad Salehi, who owns Blaze Pizza franchises in Northridge and Encino, according to a statement by the coalition.

If the council decides to pass Soto-Martinez’s motion — a vote that probably won’t happen until at least late summer or the fall — the city attorney would then be tasked with formally drafting the ordinance for final approval.

Soto-Martinez’s proposal is backed by California’s statewide union of fast-food workers, formed earlier this year. The California Fast Food Workers Union, created with help from the Service Employees International Union, is the culmination of years of employee walkouts over issues including the handling of sexual harassment claims, wage theft, safety and pay, such as the Fight for $15 movement to increase the minimum wage, which was organized by the SEIU in 2012.

“The 50,000 of us who stand to gain important protections on the job through this ordinance are not just fast-food workers, we are parents, grandparents, students and providers,” Anneisha Williams said in a statement by the union.

Williams, who works at a Los Angeles Jack in the Box, is a member of the state’s newly formed Fast Food Council.

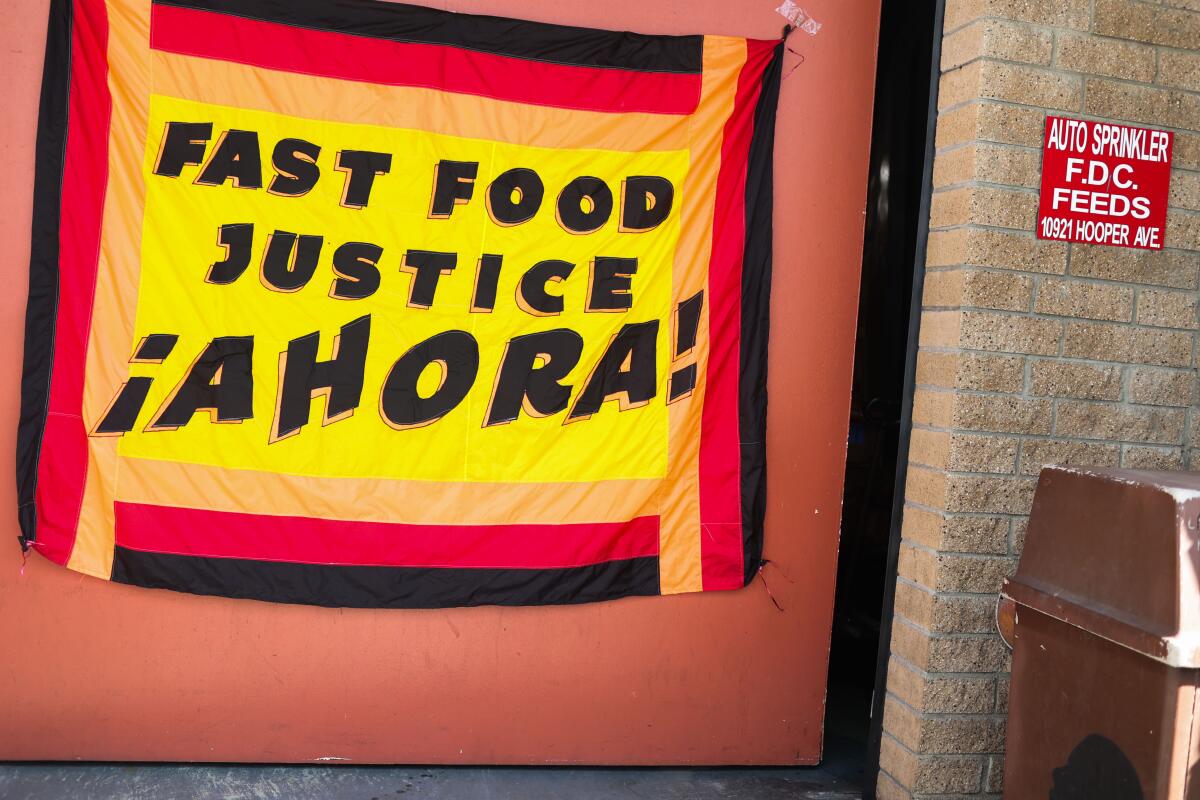

She was among scores of fast-food workers sporting purple union T-shirts who gathered outside L.A. City Hall on Tuesday morning, where Soto-Martinez announced the effort.

Julieta Garcia, 36, who has worked at a Pizza Hut in Historic Filipinotown for 1½ years, said her hours are very irregular, averaging about 20 hours a week.

“Mentally, it has hurt me — the stress of figuring out how I will cover all of my bills,” she said.

Garcia said it has also made it difficult to show up for her family. Paid time off would help her be able to attend her son’s school plays, or visit a terminally ill family member, she said.

L.A. is among several cities nationwide, including Seattle, New York and Chicago, that have adopted scheduling laws.

L.A.’s Fair Work Week law, approved by the Los Angeles City Council in 2022, already requires large retail and grocery chains such as Target, Ralphs and Home Depot to give employees their work schedule at least two weeks in advance. It further requires businesses to give workers at least 10 hours’ rest between shifts, or provide extra pay for that work.

Researchers at the Shift Project, an initiative from Harvard University and UC San Francisco that is focused on service-sector workers, have found that unpredictable work schedules lead to unstable incomes as well as poor sleep and psychological distress.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.