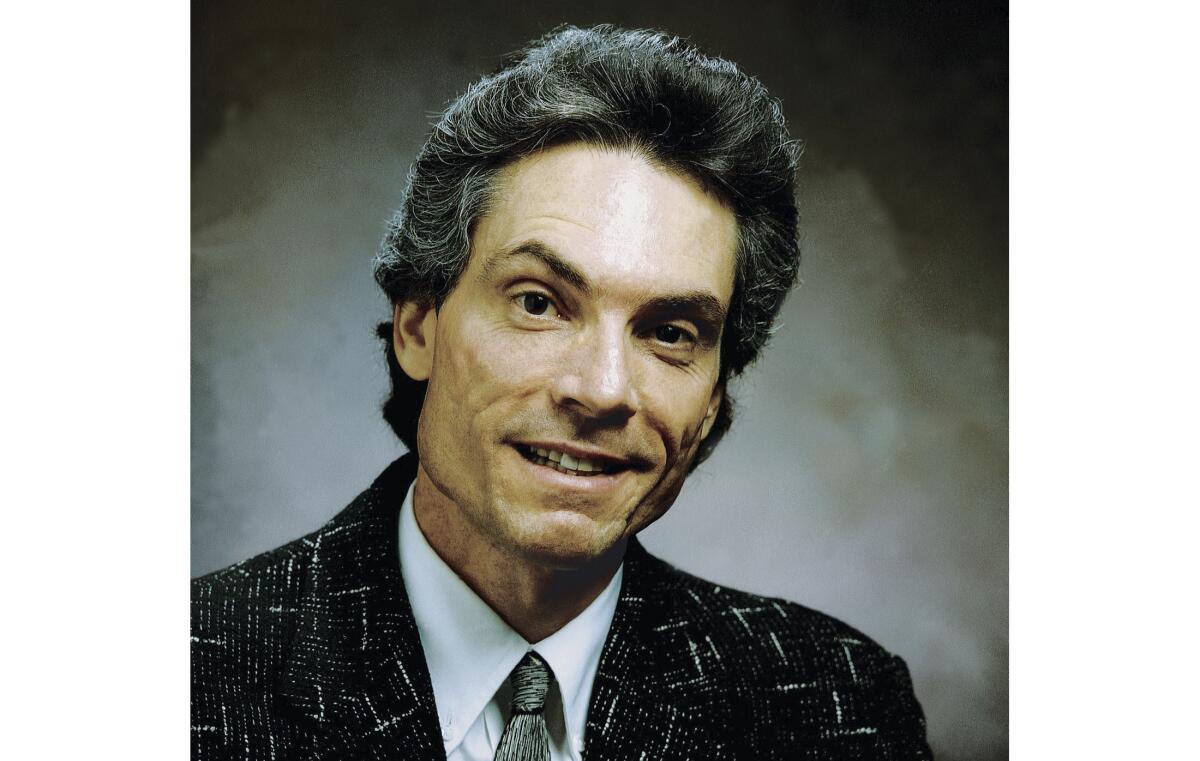

Column: Chuck Philips (1952-2024) singlehandedly made music industry journalism better

- Share via

Few people outside the music industry may know the name Chuck Philips, but few inside the industry will forget it.

As the leading music industry investigative reporter of his generation and a mainstay of Times entertainment coverage for more than a decade, Chuck aimed to force a celebrity-driven corner of journalism into taking seriously how the pursuit of money by industry bigwigs often left the artists themselves at the side of the road.

He may not have entirely succeeded — the coverage of celebrity lives is still a fundamental feature of music writing — but he set a standard that has seldom been matched. Chuck died last month at 71.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“There are two ways to look at investigative reporting in the world of pop music journalism,” says Robert Hilburn, who as The Times’ pop music critic and pop music editor began publishing Chuck’s freelanced stories in the 1980s. “There’s pre-Chuck Philips and post-Chuck Philips. Before Chuck, the coverage, nationally, was mostly timid and sporadic. Chuck turned it into something relentless and uncompromising.”

That’s a global perspective. Here’s a personal perspective, drawn from my working with Chuck on investigations of the music industry in 1998 that won us the Pulitzer Prize: Chuck was the most tenacious, scrupulous and principled journalist I’ve ever known.

There are two ways to look at investigative reporting in the world of pop music journalism. There’s pre-Chuck Philips and post-Chuck Philips.

— Former Times pop music editor Robert Hilburn

I had an elite Ivy League journalism degree and he held a baccalaureate in journalism from Cal State Long Beach and, before joining The Times, had been running a silk-screening business.

After we were paired on our project I stood in awe of his skill at interviewing reluctant subjects, identifying the crux of a tough story, and pursuing it wherever it led, while his rigorous sense of probity and commitment to fairness earned him the trust and respect even of industry executives who knew they were about to be skewered. I learned more from our partnership than I did with anyone else I’ve worked with over a long career.

Hilburn relates that in the early 1980s, he saw the need for a reporter to supplement the reviews and features that made up the bulk of pop coverage with reporting on the business side of the industry.

G irl you know it’s . . . Girl you know it’s . . . Girl you know it’s . . . Girl you know it’s . . .

“There was no place in the budget to hire a reporter,” Hilburn told me, “so I put out the word that I was looking for a free-lance, but the field was so barren that only one person responded.”

It was Chuck Philips, who had “scant experience as a reporter — just a few stories for local music publications. Yet he had an intelligence and desire in our first meeting that stood out. Unable to hire him, I took money allocated for reviews and features to pay him by the story.”

He started with a couple of stories covering a censorship case in Florida that confronted the rap group 2 Live Crew with possible criminal and obscenity charges involving its debut album. “But Chuck didn’t just stop there, he did more than a dozen follow-up stories as new developments arose,” Hilburn said.

Few stories illustrated the compassion and empathy for recording artists that infused Chuck’s work like his coverage of the Milli Vanilli scandal in 1990. Largely forgotten now, the duo of Rob Pilatus and Fabrice Morvan had burst onto the music scene with a 1988 album titled “Girl You Know It’s True.”

The album soared to No. 1 on the Billboard charts. The dreadlocked break dancers, whom Chuck later described as “a sharp-dressing dance duo on the Munich club and fashion-show circuit,” became a worldwide sensation, winning the award for best new artist at the 1989 Grammys.

The truth was that they hadn’t sung a note on the album or onstage, but lip-synced onstage and on videos to tracks laid down by freelance vocalists. They were outed at a news conference by Frank Farian, their own Germany-based producer, who evidently was trying to undercut their insistence on singing on a forthcoming release by destroying their credibility.

Chief executive C. Michael Greene has made the awards show a blockbuster. But critics question his high pay, personal style and allocation of academy’s charity funds.

“Rob” and “Fab” were showered with vilification and ridicule in the music press. Not in Chuck’s stories, however. He saw clearly that they were the victims in a scam perpetrated by Farian and abetted by what his reporting indicated was the willful blindness, if not the knowing consent, of their American label, Clive Davis’ Arista Records.

A few days after the story broke, the performers granted their first joint interview to Chuck, who showed how they had been ruthlessly manipulated by industry figures who unaccountably escaped with their fortunes and reputations intact. Underlying the fiasco, he wrote, was “the record industry’s myth-making machine built with a recording technology capable of deceit and operated by men who chose to deceive.”

In 1995, The Times finally hired him for its full-time business staff. For Chuck, covering the music industry was not about quick hits or superficial celebrity-driven stories to be turned around in a day or two, but a determined effort to gain the trust of potential sources and infuse them with a sense of responsibility for the integrity of the business.

“Chuck Philips changed my life,” recalls Terri McIntyre, who was executive director of the Los Angeles chapter of the Grammy organization when Chuck and I began investigating the organization, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, and its chief executive, C. Michael Greene. “We became trusted friends as I shared ‘off-the-record’ the horrors of my experience at NARAS and the names of many other individuals he should seek out” for further information, recalls McIntyre, who recently filed a lawsuit alleging she was raped by Greene. (Greene denies her allegations.)

“Chuck’s dedication played a meaningful and significant role in my transition from victim to survivor,” McIntyre says. “He doggedly fought for the truth.”

For Chuck, every story involved a long-term investment. He was unfailingly sincere and rigorously honest in his treatment of colleagues and record industry workers, from secretaries to executives. Chuck was one of the most gracious colleagues I ever encountered. As long as we worked together he never forgot my birthday, leaving me CDs with mixes of new music that are still in my collection.

Programs for drying out in swank settings are typically ineffective and sometimes illegal. One Beverly Hills doctor defends his high-priced service.

Chuck often took on issues that would not be taken up by the broader press for months, even years. In 1991, working with the late Laurie Becklund, he broke the story of sexual misconduct at three leading record companies and a prominent Los Angeles law firm, unearthing legal settlements and government complaints by secretaries and other women in their offices, divulging damning details and identifying the accused perpetrators by name — a quarter-century before reporting on sexual harassment in the entertainment industry launched the #MeToo movement.

For the record:

4:13 p.m. Feb. 6, 2024An earlier version of this article misspelled the last name of Larry L. Burriss, the co-author of a 2001 book on music industry controversies, as Burris.

Investigative reporters at other media outlets scurried to follow The Times’ reporting. “Chuck Philips was responsible for bringing sexual harassment in the music industry to a national forum,” Richard D. Barnet and Larry L. Burriss observed in a 2001 book on music industry controversies.

In 1994, he reported on accusations about Ticketmaster’s strong-arm tactics to preserve its near-monopoly over ticket sales at major concert venues, focusing in part on a complaint by the Seattle band Pearl Jam that Ticketmaster had pressured concert promoters into canceling dates for a national tour on which the band had tried to cap ticket prices.

In 1999, the late Mark Saylor, then the editor of entertainment coverage in The Times’ business section, was inspired to pair me and Chuck together for an investigation of the music industry. Chuck had unique access to the upper echelons of the industry and I could read a financial report.

But Chuck was the guiding spirit of the project, which began with stories exposing financial irregularities at NARAS, which sponsors the Grammys, under the all-powerful Greene — among them its spending less than 10% of the millions of dollars donated to a Grammy charity on its stated purpose of providing assistance to indigent and ailing musicians. We also reported on settlements of numerous complaints of sexual harassment by female workers at NARAS during Greene’s reign.

Greene kept his job until 2002, when the NARAS board finally ousted him after further sexual harassment cases, many of them relentlessly reported by Philips, came to light.

It must be said that Chuck was ill-served by The Times’ former management, which yielded a bitter breakup that may have contributed to his wish, communicated by his family, that no formal obituary appear, including in The Times.

The $7-billion-a-year record industry, periodically beset by controversies ranging from payola to drugs, is quietly exerting damage control over a potential new scandal: complaints of sexual harassment by some of the top executives in the business.

The inflection point came with his indefatigable reporting on the 1996 murder of Tupac Shakur. The product was a front-page article on March 17, 2008, that traced personal animosity between Tupac and the rap artist known as Biggie Smalls, or Notorious B.I.G., to a 1994 ambush at a New York recording studio at which Tupac had been robbed and pistol-whipped. The fallout from that incident, he reported, contributed to both rappers’ killings.

Chuck later recounted that he had tried to track down everyone who witnessed the 1994 assault, visiting witnesses in “prisons across the nation” and in violent neighborhoods in L.A. and New York. His story reported that information “supported Shakur’s claims that associates of music executive Sean “Diddy” Combs orchestrated” the assault; its principal target was the rap music mogul James “Jimmy Henchman” Rosemond, an associate of Combs. It was accompanied by purported FBI reports, known as 302s, of interviews with informants; the documents appeared to support Shakur’s claims, though the 2008 article didn’t hinge on those documents.

Chuck had been tipped to the documents by an associate of Henchman’s, who told him that he had filed the 302s in a lawsuit he had brought in federal court in Florida and that they made a reference to the 1994 assault.

The documents were “privileged” — meaning that because they had been filed in an earlier court case, they could be reported on without legal liability. As it happened, however, they were also fabricated. When the article ran, Chuck did not know he had been steered toward faked documents, though he realized it soon afterward. In the aftermath, he suffered the consequences.

The Times retracted the story and removed it from its website.

Chuck disagreed with the retraction, arguing that the documents had been at best peripheral to his reporting and that the article held water without them — indeed, that he had striven to minimize references to the documents in his original draft but had been overruled by editors.

In any event, his targets exploited the retraction in a concentrated campaign to undermine his credibility. Henchman, as it happens, was sentenced in 2018 to life in prison plus 30 years for ordering the murder of a rap music rival.

A few months after the retraction, Chuck was swept out of The Times in a layoff wave, ending a career as one of the most distinguished staff members in the newspaper’s history.

Chuck spent years defending himself, including via a lengthy first-person accounting in New York’s Village Voice in 2012. The retraction permanently overshadowed his career; he never again was able to secure a full-time reporting job. Now his voice is permanently stilled, but his impact on the way we try to cover entertainment lives on.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.