Column: America’s retirement system is mediocre. The new House speaker wants to make it downright awful

- Share via

Back in my school days, a “C” grade was a certification of rank mediocrity. That’s the right way to think about a recent scorecard on which the U.S. retirement system scored an inexcusably deficient C+.

That grade placed the U.S. behind Netherlands, Iceland and Israel (all A’s); and Australia, Belgium, Britain, Canada, Finland, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland (all solid B’s or B+). If you’re looking for bragging rights, the U.S. came in about even with France.

The scores come to us from the business consulting firm Mercer, which ranked 47 national pension systems for its Global Pension Index on standards such as adequacy, sustainability (including the reliability of funding) and integrity (such as the regulation of private pension providers).

The better pension systems around the world ensure that all workers are saving for their retirement. It should not be a benefit restricted to a segment of the workforce.

— David Knox, Mercer

That C+ might be just good enough for a lazy student to win through to a college degree, but for the richest country in the world with the most vigorous and diversified industrial economy, it might as well be an F.

Among the particular shortcomings of the American system identified by the Mercer team is that it leaves too many workers out in the cold, including gig workers and lower-income blue-collar employees.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That’s because, unlike some higher-scoring countries, the U.S. doesn’t require employers to provide retirement benefits to all workers. Mercer also said that rules allowing workers to tap their retirement savings early are too lenient.

“The better pension systems around the world ensure that all workers are saving for their retirement,” David Knox, a Mercer senior partner who is lead author of this year’s pension index report, told me by email. “It should not be a benefit restricted to a segment of the workforce. In addition, the better systems do not permit pension plan members to access their benefits during their working years. That is, the accumulated benefits are preserved until retirement.”

Retirement experts are also concerned that the burden of saving for retirement is increasingly placed on the workers, rather than being shouldered by their employers.

That’s the harvest of a shift among employers from defined benefit pensions, through which they carried the bulk of investment and market risk, to 401(k)-style defined contribution plans, in which workers are subjected to those risks.

“When thinking about the ways the U.S. system can improve,” says Margaret Franklin, chief executive of the CFA Institute, the organization of investment professionals that co-sponsored the report, “we must first consider ... the increased personal responsibility for retirement planning for the many individuals who lack a guaranteed pension, outside of Social Security.”

Inflation is down sharply, employment is holding steady and GDP is growing. But Americans are still blaming Biden for a lousy recovery.

The U.S. system fell a bit in its numerical score in the Mercer index, largely because of a downgrade in its integrity score, though Mercer didn’t specify what accounted for the drop. The U.S. score is still marginally higher than it had been in any of Mercer’s previous reports dating back to 2009, except for last year. Overall, the U.S. ranked 22nd out of the 47 systems in the index.

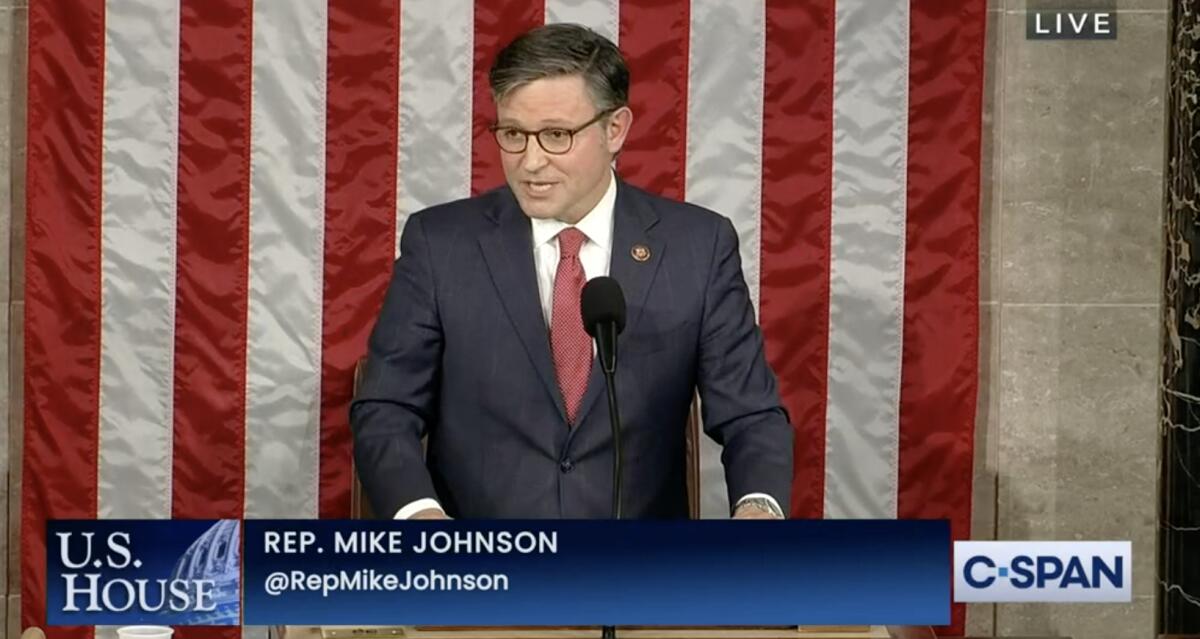

But if you’re hoping that things will improve for American retirees in the near future, the accession of Rep. Mike Johnson (R-La.) to the post of House speaker should give you pause. Johnson is a long-term advocate of cutting Social Security and Medicare benefits through changes such as raising the retirement and eligibility ages for the programs.

He also has advocated scrutinizing the cost of those programs through a “bipartisan debt commission” that inevitably would place them in the deficit-reduction cauldron along with other spending. After his rise to the speaker’s chair Wednesday, Johnson immediately promised to create this panel.

“We have to get the country back on track.... Now we know this is not going to be an easy task, and tough decisions will have to be made,” he said ominously.

Johnson’s disdain for the principles of Social Security and the implications of ostensible “reforms,” and his ignorance of its history, are manifest.

Here he is displaying all these qualities in a concentrated burst of glib, cocksure simplemindedness during a July 19, 2022, appearance on C-SPAN:

“When Social Security was created in the ‘60s, the average life span was somewhere in the mid-70s,” he said. “Now people live to be 100 routinely. So people are on the program for decades, when it was never structured to be able to do that.”

A few things about this. First and foremost, Social Security was created in 1935, not the ‘60s. Even then, the average American life expectancy for anyone reaching the age of 45 or older was more than 70. For 65-year-olds — that is, those who were eligible to begin collecting benefits — the average life expectancy was nearly 78.

In other words, Social Security was structured from the start to accommodate beneficiaries living on average well into their 70s. Its creators understood from the demographic record that life expectancy would continue to rise. Today, the average life expectancy for a 65-year-old is about 85.

Don’t listen to the doomsayers: Social Security is healthy today, and the U.S. is rich enough to improve it — if the wealthy pay their fair share.

As for Americans living “routinely” to age 100, one wonders from where Johnson could have excavated that fantastical assertion. In 2021, there were 89,739 centenarians in the U.S., out of a total population of 336 million. That works out to about 2.5 hundredths of a percent of the population. You may debate whether that’s a lot or a little, but by any standard, “routine” it ain’t.

Perhaps Johnson was drawing from the record of his home state, which has an extraordinarily long-lived populace? Sadly, no. Louisiana ranked 41st among the states in its percentage of 100-year-olds (0.016%) in 2019 — behind such paragons of public health as Alabama, Mississippi and West Virginia.

What may be more alarming is Johnson’s attempt to tie Social Security and Medicare reforms to his sociopathic view of abortion rights. During a House Judiciary Committee hearing (the date isn’t provided by the clip’s source, the committee Democrats), Johnson said:

“Roe v. Wade gave constitutional cover for the elective killing of unborn children in America.... You think about the implications of this on the economy. We’re all struggling to cover the bases of Social Security and Medicare and all the rest. If we had all those able-bodied workers in the economy, we wouldn’t be going upside-down and toppling over like this.”

He’s not the first antiabortion fanatic to cite the ostensible drag of women’s reproductive rights on the U.S. workforce as though we should be living in a “Handmaid’s Tale” dystopia. But one is accustomed to hearing this claptrap from the right-wing fringe, not from anyone reaching Johnson’s elevated position in the government.

On the whole, Johnson’s approach to social safety net programs comes right out of the GOP library of lies about the programs’ finances and their effect on the federal budget.

“The reality is, they’re headed towards bankruptcy,” he said in his July 2022 C-SPAN appearance. “In just a few number of years, Social Security goes belly up. So does Medicare, Medicaid, all of these big-spending programs because we’re drowning in debt.”

The idea that Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid are going “bankrupt” is standard Republican hogwash. So is the idea that Social Security will go “belly up” in some number of years — even if Congress sits on its hands, the program will still have enough revenue to cover three-quarters of the benefits due.

Republicans say Biden is lying about their intention to cut Social Security and Medicare. The evidence backs him up.

The notion that those programs are drivers of the federal debt is also a bog-standard GOP talking point. A far more significant portion of the federal budget deficit is the lavish tax cut that Johnson’s party gifted to corporations and the wealthy in 2017, a $1.5-trillion giveaway from which the U.S. economy received no significant gain.

Johnson voted for it. All his rhetoric about “saving” the social programs is cover for making sure that the beneficiaries of that giveaway are able to keep their money.

In measuring Johnson’s record on 10 legislative measures important to retirees, the Alliance for Retired Americans gave him a 0% score for 2022, and 5% for his entire career. He was the lowest-scoring senator or representative from his state.

Johnson voted against all 10 measures, including one aimed at ensuring voter access, an expansion of health benefits for veterans, the omnibus federal spending bill for fiscal 2022, and the Inflation Reduction Act, which incorporated the provision allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices and the cap on out-of-pocket spending on insulin for Medicare members.

The Mercer team pinpointed a handful of improvements that would raise the U.S. system’s index score in the future.

Among them is raising the minimum benefit for low-income retirees. That’s an idea that has been embraced by Social Security advocates in the Democratic Party. On the Republican side, it’s typically proposed as part of a scheme that would limit benefits for higher-income retirees.

Mercer also recommends improving vesting rights for all retirement plan members and improving inflation protection — a feature of Social Security, but not of many private or corporate retirement plans.

The experts also favor requiring part of any retirement benefit be taken as an annuity stream, which would limit the erosion of benefits taken as a lump sum and perhaps keep them from being lost to imprudent investments, while making it more likely that benefits would last for life.

None of these recommendations should be out of the question for American lawmakers serious about ensuring retirement security for American workers. Mercer is right that the American system could be vastly improved — especially if ideologues like Speaker Johnson get out of the way.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.