Column: The story behind that Florida school curriculum that whitewashed slavery keeps getting worse

- Share via

If there’s a bet that you will almost always win, it’s that no matter how crass and dishonest a right-wing claim may seem to be, the reality will be worse.

That’s the case with Florida’s effort to whitewash the truth about slavery via a set of standards for teaching African American history imposed on the state’s public school teachers and students.

The curriculum, you may recall, was condemned for a provision that the curriculum cover “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Dogs and Negroes Not Welcome

— Sign posted until 1959 at the town line of Ocoee, Florida, site of a 1920 racial massacre

Another provision seemed to blame “Africans’ resistance to slavery” for the tightening of slave codes in the South that outlawed teaching slaves to read and write.

A section referring to “acts of violence perpetrated against and by African Americans” goes on to list five race riots and massacres from American history, every one of which was started by whites.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More on that in a moment. As the indispensable Charles P. Pierce put it, the Florida standards “look as though they were devised by Strom Thurmond on some very good mushrooms.”

I reported last week on this reprehensible project, which was publicly presented as the product of a work group of the state’s African American History Task Force.

Two members of the task force, William B. Allen and Frances Presley Rice, responded to the scathing reaction to the curriculum from Democrats and Republicans with a defensive statement purportedly on behalf of the entire work group.

“Some slaves developed highly specialized trades from which they benefitted [sic],” the statement read. “This is factual and well documented.”

As I reported, however, of the 16 individuals Allen and Rice mentioned to support their assertion, nine never were slaves, seven were identified by the wrong trade and 13 or 14 did not learn their skills while enslaved. One, Betty Washington Lewis, whom Allen and Rice identified as a “shoemaker,” was white: She was George Washington’s younger sister and a slave owner.

Now it turns out that Allen and Rice were not speaking for the work group, but for themselves. Thanks to reporting by NBC News, we know that most of the work group’s 13 members opposed the language suggesting that slaves benefited from their enslavement.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis wants us to know how slaves learned their trades in bondage, but he gets everything dead wrong.

NBC quoted several members anonymously as stating that two members pushed the provision — Allen and Rice. Members “questioned ‘how there could be a benefit to slavery,’” one work group member told NBC.

Others said that the work group met intermittently over the internet and did not collaborate with the state’s African American History Task Force, which was created in 1994 to oversee the curriculum for African American studies in Florida’s K-12 schools.

The work group’s standards were approved unanimously on July 19 by the state board of education, every member of which was appointed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, who is running a natural experiment to see whether bigotry and racism can carry someone to the presidency.

We’ve recently learned more about Allen and Rice. Allen, as I reported earlier, is a retired professor of political science at Michigan State University. (The university removed his bio page from its website sometime in the last few days, but here’s an archived version.)

Allen served as chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights under George H.W. Bush, but angered civil rights activists and members of the commission itself for taking a stand against legal protections for gay people.

At a 1989 conference in Anaheim sponsored by anti-gay Christian fundamentalists, Allen delivered a talk titled, “Blacks? Animals? Homosexuals? What is a Minority?”

Its theme was that treating gays and Black people as distinct minorities would relegate them to animal status. Allen said, “My title is as innocent as a title can be,” a position that prefigured his current defense of the Florida slavery standards as no big deal.

He’s listed as a fellow of the Claremont Institute, which has been funded by a galaxy of right-wing foundations. The institute lists among its senior fellows John Eastman, who is one of the four attorneys identified as “co-conspirators” in the federal indictment of former President Trump for trying to overturn the 2020 presidential election, handed up Tuesday. Eastman is also the target of a California State Bar proceeding aimed at his disbarment for his alleged role in that effort.

A federal judge’s rejection of Florida’s law banning transgender treatment adds to the growing pile of court rulings overturning Ron DeSantis’ campaign of bigotry.

As for Rice, she’s chair of the Sarasota-based National Black Republican Assn., which appears to have shared its business address with her home address. She identifies herself as “Dr. Frances Presley Rice,” but she doesn’t appear to have a medical degree or PhD; she does hold a juris doctor degree, but that’s just a law degree and doesn’t customarily bestow the “Dr.” designation on its holders.

Rice has conducted a years-long campaign to associate today’s Democratic Party with the Democrats of the 19th century, a pro-slavery party that shares none of its positions on Blacks or slavery with the Democrats of modern times.

The normalization of Florida’s slavery whitewash has been abetted by a supine press. On July 27, for example, Steve Inskeep, the host of NPR’s Morning Edition, conducted a servile interview in which he sat meekly by as Allen spewed unalloyed hogwash.

When Allen suggested that Black journalist Ida B. Wells had drawn “inspiration” from the slavery experience, Inskeep — had he been even minimally prepared — could have pointed out that the Mississippi-born Wells was 5½ months old when the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on Jan. 1, 1863, and 3½ years old when the 13th Amendment abolished slavery.

Nor did Inskeep challenge Allen about the list of 16 supposed slaves that he and Rice issued in defense of their curriculum. The list had been out for a full week before the NPR interview. Inskeep didn’t mention it at all.

When Allen asserted that he was not the author of the curriculum, nor were any other members of the work group, the proper follow-up would have been: “Who wrote it, then?” Inskeep kept mum.

The Washington Post, meanwhile, tried to shoehorn Florida’s whitewashing of slavery into a “both-sides-do-it” framework.

The Post article suggests that the Florida curriculum and President Biden’s July 25 proclamation of a national monument dedicated to Emmett Till, a Black teenager tortured and lynched by a white mob in Mississippi in 1955 for purportedly offending a white woman, are two sides of a “roiling debate” over Black history.

On the first day of Black History month and after right-wing complaints, the College Board issues a watered-down Black studies curriculum. So much the worse for students.

Of course that’s absurd. Most Americans, and most Democrats, don’t see slavery as a topic worthy of reconsideration. That’s all on the Republican side, especially in Florida.

DeSantis and his stooges are pretending that the truth about America’s racist past should be suppressed for fear of making white children feel bad. It’s nothing but a play for the most bigoted members of the GOP base.

That brings us back to Florida’s curriculum. Provisions other than the one about the benefits of slavery aren’t getting the attention they deserve.

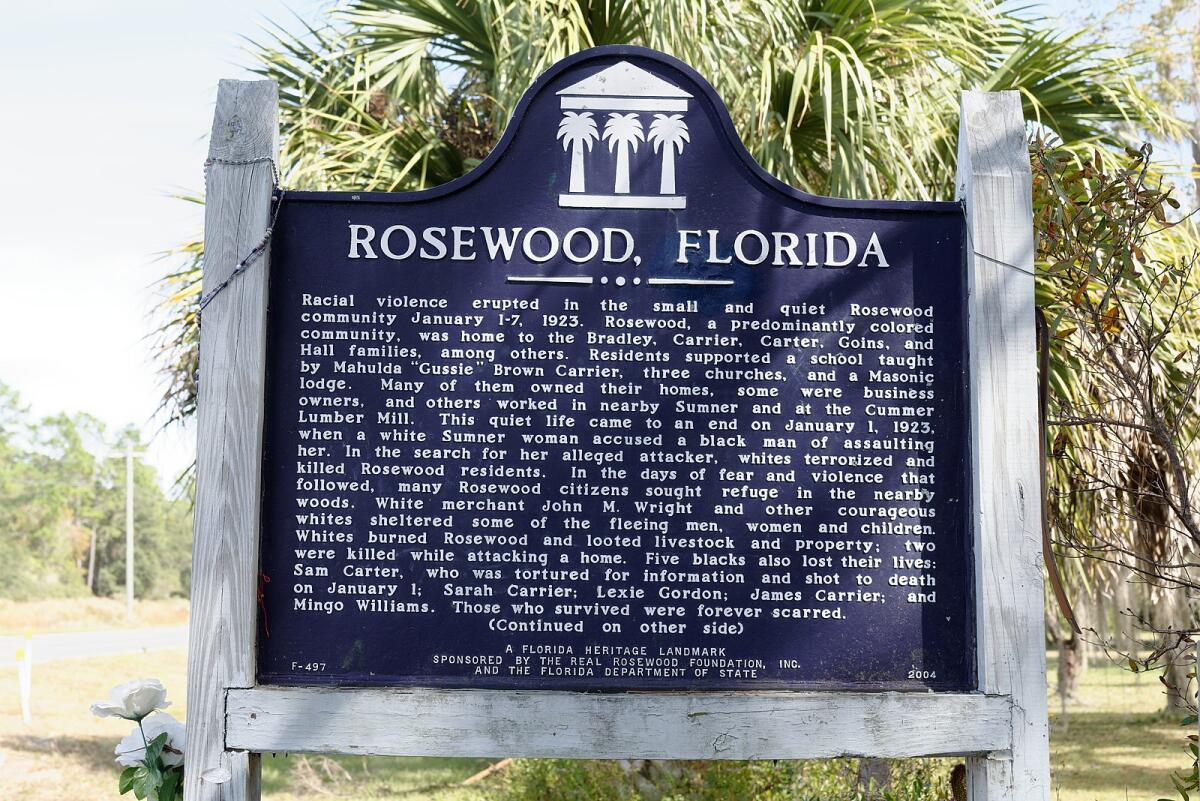

Take the part about “acts of violence perpetrated against and by African Americans.” This standard is illustrated in the text by references to race riots in Atlanta in 1906 and Washington, D.C., in 1919, and massacres in Ocoee, Fla. (1920); Tulsa (1921); and Rosewood, Fla. (1923) — rampages by white mobs lasting a day or more.

In what sense do these point to violence perpetrated by Black people? Pierce conjectures that they “might distressingly be referring to attempts by the victims of those bloody episodes to fight back.”

The Ocoee massacre occurred when the town’s Black residents attempted to vote. When a squadron of Klansmen hunted down a Black leader in his home, his daughter tried to prevent them from taking him by brandishing a rifle, which went off, slightly wounding a white member of the gang.

“A volley of gunfire erupted in both directions,” according to an account on the Florida History blog. In the aftermath, nearly 60 Black residents were dead, their community was razed to the ground, and those who survived were driven from the town, never to return. Until 1959, a sign at the town line read, “Dogs and Negroes Not Welcome.”

Is Ocoee supposed to be an example of “violence perpetrated ... by African Americans”? Nothing would speak more eloquently to the true nature of the Florida standards for teaching Black history.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.