Should California make solar more expensive? Inside the climate justice battle

- Share via

Parakeets and lovebirds were chirping in Marta Patricia Martinez’s frontyard as a crew of solar installers climbed onto her roof.

It was a warm summer afternoon in Watts, a predominantly Latino and Black neighborhood in South Los Angeles. Low-income families faced the specter of punishingly high energy bills if they cranked up the air conditioning.

For Martinez, solar panels offered an almost-too-good-to-be-true solution.

Her electricity bills would probably drop by about 90%. And her family was getting the clean power system free, thanks to state funding secured by GRID Alternatives, the Oakland nonprofit installing the rooftop panels.

“Solar’s not about tomorrow. It’s about today,” said Darean Nguyen, a supervisor on the installation crew.

But even as the heat waves and wildfires of the climate crisis worsen — and as monopoly utility companies struggle to keep the lights on — Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration could soon make it harder for many families to go solar.

State officials have been laying the groundwork to slash a key solar incentive program called net energy metering, with a decision expected this year. The program’s critics — including utility giants, ratepayer watchdogs and some environmental justice activists — insist net metering is fundamentally inequitable, widening the gap between rich and poor.

Solar companies and many climate activists disagree. They say gutting incentives could cause installations to plummet on single-family homes, apartment buildings, businesses and schools.

“We will fall horribly short of our clean energy goals if we kill the rooftop solar market,” said Bernadette Del Chiaro, executive director of the California Solar & Storage Assn. “Solar is going to go back to the time when it’s only for the super wealthy.”

A bitter fight over the merits of rooftop solar might seem wildly out of place in eco-friendly California.

But the battle lines aren’t as simple as climate champions on one side and science deniers on the other. The debate has raised thorny questions about economic and racial justice and gotten tangled up in the third-rail politics of organized labor.

It has also exposed diverging visions of the clean energy future: One in which society is mostly powered by rooftop solar panels, and another in which the utility electric grid maintains its dominance, with distant solar farms replacing distant coal plants.

Both technologies will be needed to confront global warming. But the balance that’s ultimately struck — between sprawling energy infrastructure covering huge amounts of land, and what rooftop solar advocates call “energy democracy” — will help determine who pays and who profits, and what America looks like when the dust settles.

Here’s what’s at stake

Net energy metering has helped make California a solar powerhouse, with more than 1.3 million systems installed.

The program works by crediting solar-powered homes and businesses for the electricity they export to the utility grid. They still have to pay for electricity they draw from the grid when solar isn’t enough. But the credits lower their monthly bills.

Record heat. Raging fires. What are the solutions?

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter about climate change, the environment and building a more sustainable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Net metering doesn’t pencil out for everybody — going solar can cost tens of thousands of dollars, and it’s often not possible for renters. But for those who can pay or qualify for a loan, the affordability of solar typically comes down to the “payback period” — the number of years it takes to make back their investment through lower electric bills.

The average home served by Southern California Edison can make back its solar investment in five years, according to an analysis by consulting firm E3. Under the utility industry’s proposed changes to net metering, that would grow to 17 years for new solar adopters served by Edison and 21 years for those served by Pacific Gas & Electric — making solar a tougher financial lift.

Rooftop solar proponents are convinced that Edison, PG&E and San Diego Gas & Electric are motivated by money.

The companies don’t make a profit on electricity sales, but they do generate substantial returns for their shareholders when they build transmission lines and other infrastructure. The continued growth of rooftop solar threatens that business model, critics say.

“The utilities have cooked up a PR campaign to convince everybody that their way is the superior way to go,” Del Chiaro said.

The argument against net metering goes like this: When solar homes lower their energy bills, utility companies collect less revenue. As a result, state regulators have no choice but to let them raise electricity rates for everyone, to help pay for projects such as hardening power lines to prevent wildfire ignitions and installing batteries to keep the lights on after dark.

And because solar customers are wealthier than the population as a whole, net metering works like a subsidy from the poor to the rich, the policy’s critics say. The amount of money transferred from non-solar households to their net-metered neighbors amounts to $3.4 billion per year in California, the utility industry estimates — a figure known as the cost shift.

“The program has to change,” said Caroline Choi, Edison’s senior vice president of corporate affairs. “It’s not sustainable when the folks who are least able to afford it are subsidizing those who do have the opportunity.”

Jonathan Scott, from HGTV’s “Property Brothers,” says power companies across the country want to stop you from going solar.

The cost shift argument has also been trumpeted by labor unions representing utility workers, who have a vested interest in protecting their employers’ business model. They say they’re trying to keep energy affordable for everyone.

“In 2021, rooftop solar will take $3 billion out of the pockets of most California electric customers and put it in the pocket of a small group of customers who are typically richer, whiter and live in single-family homes,” said Marc Joseph, an attorney representing the Coalition of California Utility Employees and the California State Assn. of Electrical Workers.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, an influential environmental group, has also sounded the alarm about the cost shift, calling for changes to net metering that could double the solar payback period. Two respected consumer watchdogs, the Utility Reform Network and California’s Public Advocates Office, want to see even larger reductions to solar incentives.

All three are asking for changes that could lead to higher monthly bills for homes that already have solar panels — unlike the utility companies, which have only proposed revamping net metering for new solar adopters.

“This is a serious injustice that we’re trying to correct,” said Matthew Freedman, an attorney at the Utility Reform Network.

Solar advocates counter that the technology is getting cheaper and is no longer exclusively for the wealthy.

Data from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory show that 12% of California solar adopters in 2019 had incomes below $50,000, and an additional 29% had incomes between $50,000 and $100,000 — up from 9% and 24%, respectively, a decade earlier.

Solar installers and many climate activists see the cost shift argument as a farce.

They say utilities are undercounting the savings that rooftop solar brings to all Californians by limiting the need for expensive new power plants and transmission lines — not to mention the health benefits of less pollution from burning fossil fuels. They also say rooftop solar paired with batteries can serve as a backup power source when utilities shut off electricity to stop their equipment from sparking wildfires — or when fires, storms and other weather events exacerbated by climate change knock out the grid.

Research from Vibrant Clean Energy backs up those claims.

With funding from solar advocates and installers, the consulting firm found that nearly eliminating U.S. climate pollution would be $473 billion cheaper with dramatic growth in rooftop and community solar and batteries. California in particular could save $120 billion by building out six times the amount of small-scale solar installed today, along with lots of batteries, Vibrant estimated.

“We’re going to need hundreds of thousands of megawatts going onto the grid [nationally] by 2050 no matter what we do,” said Vibrant Chief Executive Chris Clack, an energy systems researcher. Building lots of rooftop solar “makes it easier and cheaper.”

A bruising political battle

Not all researchers agree with that assessment.

UC Berkeley energy economist Severin Borenstein — who leads an institute that receives small amounts of utility funding — said Vibrant’s models exaggerate the case for rooftop solar. Borenstein has written that net metering “hurts the poor. It’s that simple.”

State officials seem sympathetic to that argument.

The California Public Utilities Commission — which will decide what changes, if any, to make to solar incentives — recently cited net metering as one of several factors driving up electricity rates. The costs of the solar program are “disproportionately paid by younger, less wealthy, and more disadvantaged ratepayers, many of whom are renters,” commission staff wrote.

Electric vehicles, plug-ins hybrids and rooftop solar installations are way more common in wealthier parts of Los Angeles County.

State Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo, a Los Angeles Democrat, pressed commission President Marybel Batjer on net metering this summer, asking why the agency hadn’t yet addressed the cost shift. Batjer acknowledged “the inequity or the unfairness of the current structure” and promised a decision on the program’s future soon.

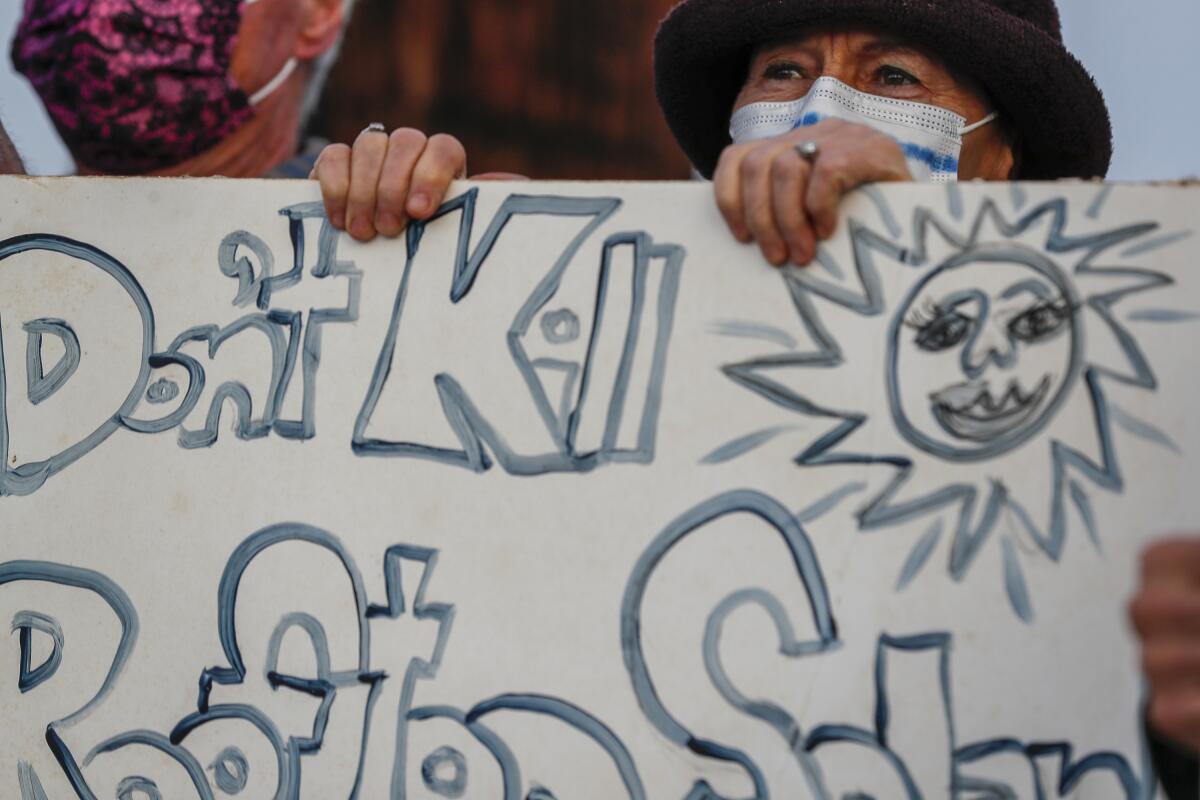

Carrillo was one of two lawmakers behind Assembly Bill 1139, which would have compelled the utilities commission to take a cudgel to net metering. The bill failed in the face of furious opposition from environment activists and solar firms, but not before a showdown on the Assembly floor that saw 27 lawmakers vote to slash solar incentives — all of them Democrats.

Why was there so much support for the bill? In part because it was sponsored by politically powerful organized labor.

It’s not just utility employees fighting to undercut rooftop solar incentives. Union electricians prefer large solar farms because they’re typically built by union labor in California, unlike rooftop panels, which are installed mostly by nonunion workers.

California is a test case in President Biden’s efforts to demonstrate how fighting climate change is good for the economy.

The bill’s other author, Assemblymember Lorena Gonzalez, bristled at accusations of being a stooge for organized labor. The San Diego Democrat, a former union organizer, at one point called her critics “self-proclaimed ‘environmentalists.’” When a political consultant tweeted that her bill was “a power & money grab of big utilities,” she responded, “Don’t parrot corporate solar.”

“What I’m trying to do is lower the rates of the vast majority of my constituents, 99% of them,” Gonzalez said in an interview.

The sparring is no less fierce now that the debate has moved to the Public Utilities Commission.

Parties on all sides, from the solar industry to the utilities, say their net metering proposals would help low-income families. And even the program’s harshest critics say rooftop solar must keep growing in California for the state to meet its climate goals.

But accusations of bad faith have run rampant.

The Solar Rights Alliance, for instance, accused the Utility Reform Network of “using their reputation to attack rooftop solar” and “promoting false claims.” The consumer watchdog’s executive director, Mark Toney, responded that his organization “is a leader in fighting utility rate increases and supporting a rapid transition to a clean energy economy.”

Other solar supporters created a petition slamming the AARP for “pushing the utilities’ agenda.” AARP has defended its advocacy.

Asked about the Natural Resources Defense Council’s plan to overhaul net metering, the solar industry’s Del Chiaro suggested the environmental group has too close a relationship with utility companies to be trusted. She pointed to NRDC’s history of collaboration with the Edison Electric Institute, a trade association for investor-owned utilities including Edison and PG&E.

NRDC senior scientist Mohit Chhabra said the group’s work is independent of the utility industry.

“We need to move toward a place where we incentivize rooftop solar predominantly for low- and middle-income Californians, and we also incentivize putting rooftop solar and storage in the right places on the grid,” Chhabra said in an interview.

Two visions of environmentalism

Beneath the political and technical disputes is a stark philosophical divide.

At one end are environmentalists who deeply mistrust big utilities and think regular people have a right to generate their own power. Some are conservationists who don’t want to see massive solar farms disrupt sensitive ecosystems and scenic landscapes.

“Distributed solar is such a no-brainer — to put your solar right there and share it with your neighbors,” said Sara Lee, a teacher and activist who helped organize a protest of Assembly Bill 1139 outside Carrillo’s Echo Park office.

At the other end of the divide are environmentalists who see existing institutions — including big corporations and the utility grid — as the fastest, easiest way to tackle global warming. They agree that rooftop solar is important for reducing emissions but also cite research showing it’s more expensive than large solar farms, which benefit from economies of scale.

To Borenstein, the reality is that solar homes still depend on utility poles and wires, since they export power to the grid at certain times of the day and draw power from the grid at others. With net metering, he said, they’re “free riding on the system.”

Borenstein and other critics say net metering could actually hurt California’s climate quest by driving up energy costs. Keeping power affordable is crucial to persuading more people to buy electric cars and install electric heat pumps in their homes — key strategies for reducing climate pollution, and also a huge opportunity for electric utilities to grow their sales.

“Our business strategy is tied to the goals of the state,” Edison’s Choi said.

Curtis Stone has been using induction cooktops for years.

To show grass-roots support for their rooftop solar stance, the utilities launched the Affordable Clean Energy for All campaign, which has attacked net metering. The campaign lists more than 100 supporters, including the California Latino Leadership Institute, the Center for Asian Americans United for Self Empowerment and the Sacramento Black Chamber of Commerce.

But two-thirds of those supporters received funding from Edison, PG&E, SDG&E or SDG&E sister company Southern California Gas Co. last year, or currently list a sponsorship from one of those utilities on their website, a Times analysis found.

Kathy Fairbanks, a partner at the public relations firm running the campaign, said in an email that each group “weighed the [solar] policy on its merits and concluded it needs reform.” Still, she acknowledged the utilities are the campaign’s only funders.

“The solar industry has also hired PR firms, just like ours,” she said.

Solar advocates say they’re the ones with true grass-roots support on their side. About 350 groups — including organizations focused on climate action, public health, conservation and equitable housing — are part of the Save California Solar campaign, which has received solar industry funding and is urging the Public Utilities Commission to protect net metering.

Who pays, and who profits

As the net metering debate nears its endgame, leading environmental justice advocates are carefully weighing in.

Groups including the California Environmental Justice Alliance and Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability said in a September statement that the solar program “disproportionately benefits wealthier, white, single-family homeowners.”

But they didn’t take a position on the cost shift question. Instead, they offered ideas for helping low-income renters and people of color benefit from clean energy, such as building “community solar” facilities that serve entire neighborhoods.

Solar incentives, they wrote, must “prioritize the needs of the communities most harmed by historic pollution.”

“There’s an excitement about solar, especially among the folks we work with. But there’s a lot of support needed,” said Amee Raval, policy and research director at Asian Pacific Environmental Network, one of the groups behind the statement.

Support our journalism

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

Other environmental justice activists are defending net metering. The newly formed Coalition for Environmental Equity and Economics, which has received funding from Save California Solar, sent Newsom a letter accusing the utilities of “race-baiting.”

“We have to tell the truth, which is that [rooftop solar] is and can be readily available for most communities,” said the Rev. Ambrose Carroll, founder of Green the Church and one of the equity coalition’s leaders. “We have to fight for it.”

Whatever the Public Utilities Commission decides, going solar won’t be as easy for most people as it was for Marta Patricia Martinez, because most people won’t have their costs covered by a nonprofit such as GRID Alternatives.

But GRID strategy officer Danny Hom, standing in Martinez’s Watts backyard, said net metering is crucial for low-income homes.

Families such as Martinez’s, he said, are unlikely to see significant cost savings from solar without some version of the program.

“We see all the time how this is transformative for people,” he said. “What I hear a lot, especially as it gets hot, is, ‘I don’t want to run air conditioning because it’s too expensive.’ In a lot of cases, older people’s electricity usage may actually go up once they get solar, because they’re able to do things that are comfortable for themselves without worrying that they’re going to spend $300.”

As for Martinez? She said she planned to use the solar savings for her first trip home to Guatemala in more than a decade.

More to Read

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.