Column: Hospital mergers reduce patient care and drive up prices, new data show

- Share via

The new year is certain to bring a new wave of hospital mergers, as does almost every year — at the pace of about 100 deals annually.

But 2020 also brings us new data on the effects of these mergers. According to a team from Harvard and two Boston hospitals, the deals resulted in worse patient experiences and no improvement in clinical outcomes.

As the researchers point out, abundant studies have shown that mergers drive up prices, typically by giving merged systems more bargaining power with payers such as insurance plans.

When big hospitals merge, the merger partners’ mantra is almost always the same: The deal will deliver lower costs to the lucky patients, with no sacrifice in quality.

“These findings challenge arguments that hospital consolidation, which is known to increase prices, also improves quality,” the authors, led by Nancy D. Beaulieu and Leemore S. Dafny of Harvard, wrote in an article published Thursday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The research is important because the rate of hospital mergers shows no signs of abating; the pace of deals remains strong and their value has been consistently increasing as big hospital systems sweep up smaller chains.

These findings challenge arguments that hospital consolidation, which is known to increase prices, also improves quality.

— Beaulieu, Dafny et al

As the healthcare merger and acquisition firm Kaufman, Hall & Associates has reported, 2018 saw a surge in “mega-mergers,” with the size of the acquired systems continuing a decadelong upward trend. The average revenue of the acquired systems reached $600 million in the second quarter of 2019, half again as large as the $400-million average of 2018.

Those deals may make financial sense for the participating systems, but not necessarily for patients. Their tendency to push up prices has long been known. A perfect example is what has been seen in Northern California from the expansion of the Sutter Health system through aggressive acquisitions.

Sutter late last year settled an antitrust lawsuit brought by California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra along with employers and unions for $575 million. Becerra had alleged that Sutter, a nonprofit chain that is the dominant hospital system in Northern California, ruthlessly exploited its size and reach to extract “illegally inflated prices” from insurers, employers and patients. The result was in-patient costs in Northern California that are as much as 70% higher than in Southern California, where Sutter has no presence.

The debate over hospital mergers traditionally has focused on whether allowing hospitals within a local community to merge drives up prices in that community.

In the settlement, Sutter agreed to end practices that were at the core of the lawsuit, including all-or-nothing terms requiring insurers to contract with all Sutter hospitals if they wanted to contract with any of them. Sutter didn’t admit wrongdoing in settling the case.

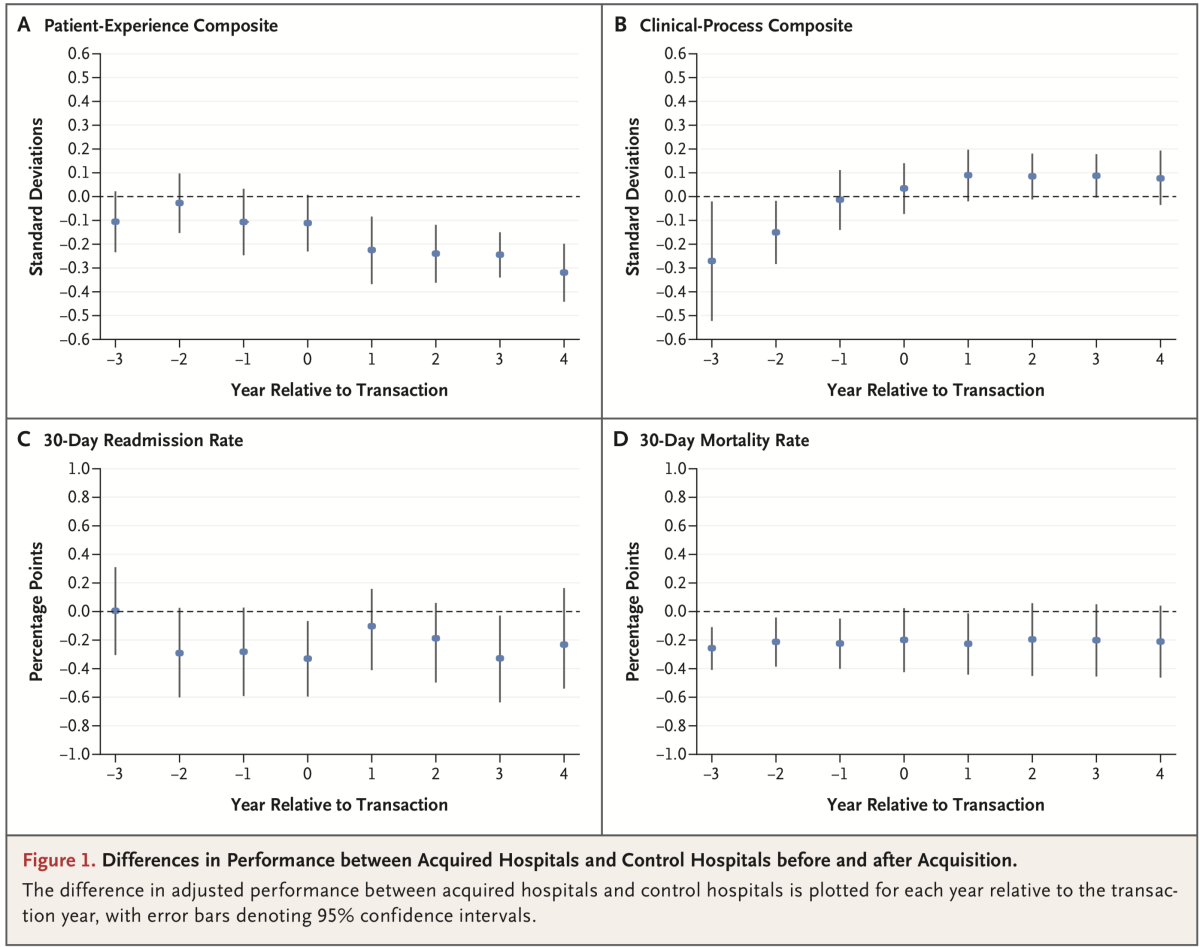

The clinical impact of hospital mergers has been harder to pin down than the financial consequences. The new study compared patient experiences and outcomes at 246 hospitals acquired from 2009 through 2013 with similar data from 1,986 unacquired control hospitals. The sample comprised short-term, acute-care hospitals with at least 25 beds and at least 100 Medicare admissions per year.

The researchers found what they called a “modest” but consistent decline in patient experience measures over the four years following the acquisitions. The “decline in performance,” they wrote, “was not a continuation of preexisting trends, was not explained by changes in the patient populations ... and is consistent with expectations that some acquired hospitals face less competition after acquisition.” They wrote that they were unable to pinpoint why these changes occurred.

The patient experience measurements were those used by Medicare’s Hospital Consumer Assessment survey, which covers such categories as communication with nurses and doctors, responsiveness of hospital staff, cleanliness and quietness of the hospital environment and communication about medicines. These are important because they’re factors that patients will notice without professional input.

The researchers also found, however, “no evidence of quality improvement attributable to changes in ownership.” That included “no detectable changes in readmission or mortality rates at acquired hospitals.” Those are key measures of hospital inpatient outcomes, but involve professional analysis rather than laypersons’ impressions.

But the fundamental conclusion is especially valuable: When big hospital systems promise that their mergers will bring terrific benefits to patients, don’t take them at face value.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.