Food-delivery start-ups are fattening up on technology

- Share via

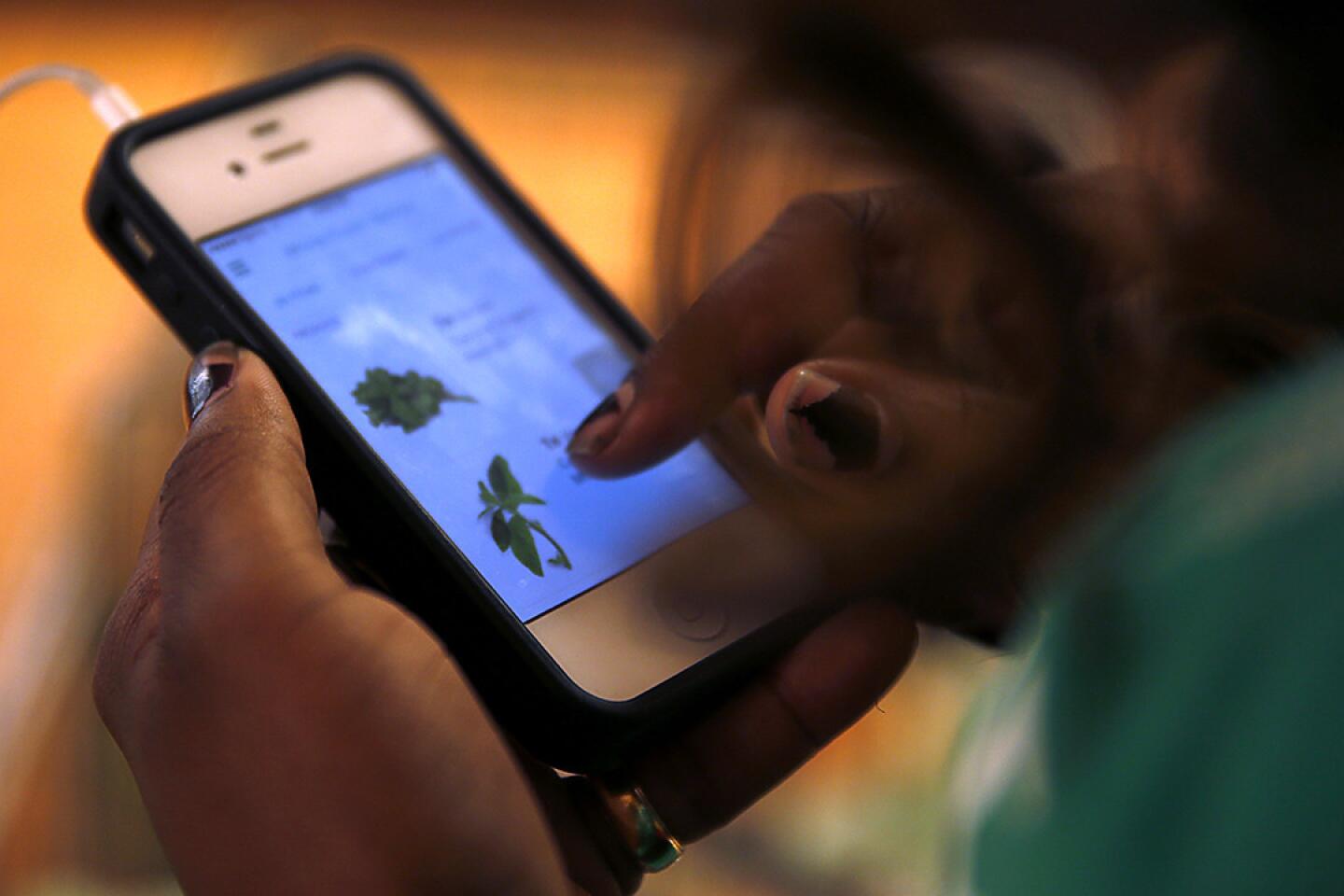

Cassandra Santana rarely has time to shop for food, let alone cook it.

The Venice social media manager gets groceries delivered weekly to her house. She also orders on a regular basis from trendy restaurants such as Gjelina for delivery to her home or workplace.

“Just a year ago, I would be running to the grocery store, and I hate going to the grocery store,” said Santana, 28. “Now I have all the food options in the world at my fingertips.”

Technology entrepreneurs have revolutionized the way people shop for clothing, find vacation rentals and flag down taxis. Now they’re shaking up the world of eating.

Whole Foods Market Inc. is partnering with start-up Instacart to deliver groceries to shoppers’ doorsteps, and tech behemoths Amazon.com Inc. and Google Inc. are also testing delivery services.

A new crop of start-ups is popping up that carry piping-hot meals to homes or offices from fancy restaurants that normally don’t deliver. Some will deliver pre-sliced ingredients for a gourmet meal to your doorstep. Others are aggregating local chefs in an easy-to-search website to cook for your next dinner party.

Helping drive this golden period in food innovation: busy Americans who have less time to cook and are keener than ever to boast on Instagram about their delicious meals. Many new companies cater to affluent shoppers working around food allergies or on trendy diets that ban entire food groups.

Investors are jumping into the food space. GrubHub Inc., the owner of delivery service Seamless, raised $192 million in an initial public offering this year. Mobile payment firm Square recently snapped up restaurant delivery start-up Caviar.

Nearly $4 billion was invested in food-related tech companies in the first half of 2014, more than double the $1.6 billion invested all of last year, according to food consulting firm Rosenheim Advisors. Investments in 2013 were up 33% over the year before.

“There is definitely a lot more money pouring into food,” said Brita Rosenheim of Rosenheim Advisors. “Everybody eats — if there is a bigger market opportunity than that, I don’t know what it is.”

Start-ups and investors alike are quick to point out that smartphones — and the up-to-the-second data they provide — are a crucial tool separating food innovators today from ancestors such as Webvan and Kozmo, which crashed with the dot.com bubble of the early 2000s.

Tony Xu, chief executive of start-up DoorDash, said 90% of the company’s time is spent perfecting the algorithm behind the automated delivery system. The Palo Alto company delivers from buzzed-about restaurants such as Milo & Olive and Superba Food + Bread, which often do not deliver on their own.

The algorithm calculates factors including road conditions, customer location, how busy restaurants are, driver performance and the desired temperature of the food (cold sushi versus hot pizza), pinpointing the right driver and the optimal delivery route.

“The logistics and time prediction uses information gathered from smartphones,” Xu said. “It’s very hard for a human to make that decision, especially with thousands of drivers. The decision here gets done in seconds.”

Jon Swire, owner of barbecue joint Chop Daddy’s in Venice, said working with delivery start-ups enables restaurants to appeal to new diners without the headache of managing a delivery staff. Chop Daddy’s works with DoorDash and has previously used GrubHub; it will continue outsourcing delivery as it expands to as many as 15 locations in coming years, he said.

“As an owner, it’s fantastic because these are incremental sales that aren’t stretching my fixed costs,” Swire said. “My kitchen staff is there either way.”

Food-delivery companies such as Instacart also no longer need to pour millions into warehouses, delivery trucks or inventory.

Just as people with a car can become a taxi service on Uber or Lyft using a smartphone, Instacart’s “personal shoppers” are actors, retirees and college students with vehicles and in need of a job, said Walker Dieckmann, the grocery delivery’s manager in Los Angeles.

Instacart partners with supermarkets such as Ralphs and Bristol Farms, and its website lists the available inventory for sale at each store. It recently began embedding workers in some Whole Foods Markets in Boston and Austin. Texas, who will quickly shop and package orders for home delivery or in-store pickup.

Customers drop items into a virtual basket, and then Instacart dispatches someone who shops the supermarket using a specially created app. The smartphone app maps the store and suggests ways to tackle the list efficiently by aisle. Employees are trained to spot a ripe melon or avocado, and also call customers to suggest substitutions if an item runs out.

“Your shopper will call you and ask, ‘They didn’t have the Gala apples you wanted, but they had Fujis or Pink Ladies, do you want that instead?’” Dieckmann said.

Tricia Carr, 40, said she has saved hours every week since discovering Instacart. The Burbank resident has trouble digesting grains and follows the popular Paleolithic diet, eschewing dairy products and grains in favor of leafy greens and meat. Her work as the director of mixology for Southern Wine & Spirits in Southern California also required frequent trips to pick up cocktail ingredients.

Instead of all-too-frequent treks to the grocery store, Carr now fires up her laptop and gets her food delivered within two hours. She has been to the supermarket only a few times in the last month, and has also recently tried start-ups that deliver restaurant food and farmers’ produce.

“It saves me so much time,” Carr said. “My husband and I are very particular about our diets, so it’s not an option for me to run by the Jack in the Box.”

Alfred Lin, a partner at venture capital firm Sequoia Capital, said food start-ups can bring modern tech to the problem of making a profit in a traditionally low-margin business. His firm has invested in several companies, including DoorDash, Instacart and Good Eggs.

Despite carrying around “scar tissue” from backing Webvan, a delivery service that went belly-up in 2001, Sequoia still sees opportunities in the intersection of food and tech, Lin said.

“Food is still one of the biggest expenses in any person’s budget after maybe rent,” he said. “There is room to make money when you are smart.”

Many fans of modern food start-ups are twenty- and thirty-something professionals groomed by the Food Network and farm-to-table movement to love fresh, wholesome food. But they have little time or desire to learn how to cook, especially from scratch.

Companies such as Blue Apron, HelloFresh and Plated deliver meal kits that have ingredients pre-measured and ready for the frying pan. Forage, a start-up that launched in August, provides all the makings for re-creating a meal from popular restaurants such as Hapa Ramen and Alta in San Francisco.

Daniel Finley is a fan of Kitchensurfing, a company that serves as an online marketplace for chefs.

Kitchensurfing’s website gathers chefs willing to hire out their services for a few hours at a private home or event, and lists their suggested prices and sample menus.

The 33-year-old lawyer threw two dinner parties this summer using Kitchensurfing chefs. The first served Italian cuisine, and the second dished up New American fare. Costs came out to $70 to $80 a head for a five-course meal: cheaper, Finley said, than at a restaurant.

The Hollywood resident said he loves food — but not cooking. “I didn’t have the skills to do it, and I didn’t have faith that a traditional catering company could offer something compelling,” he said. “Both times, it was as good as a restaurant, if not better.”

Twitter: @ByShanLi

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.