Festival of Books: Roy Choi and Josh Kun on food, politics and L.A. history

- Share via

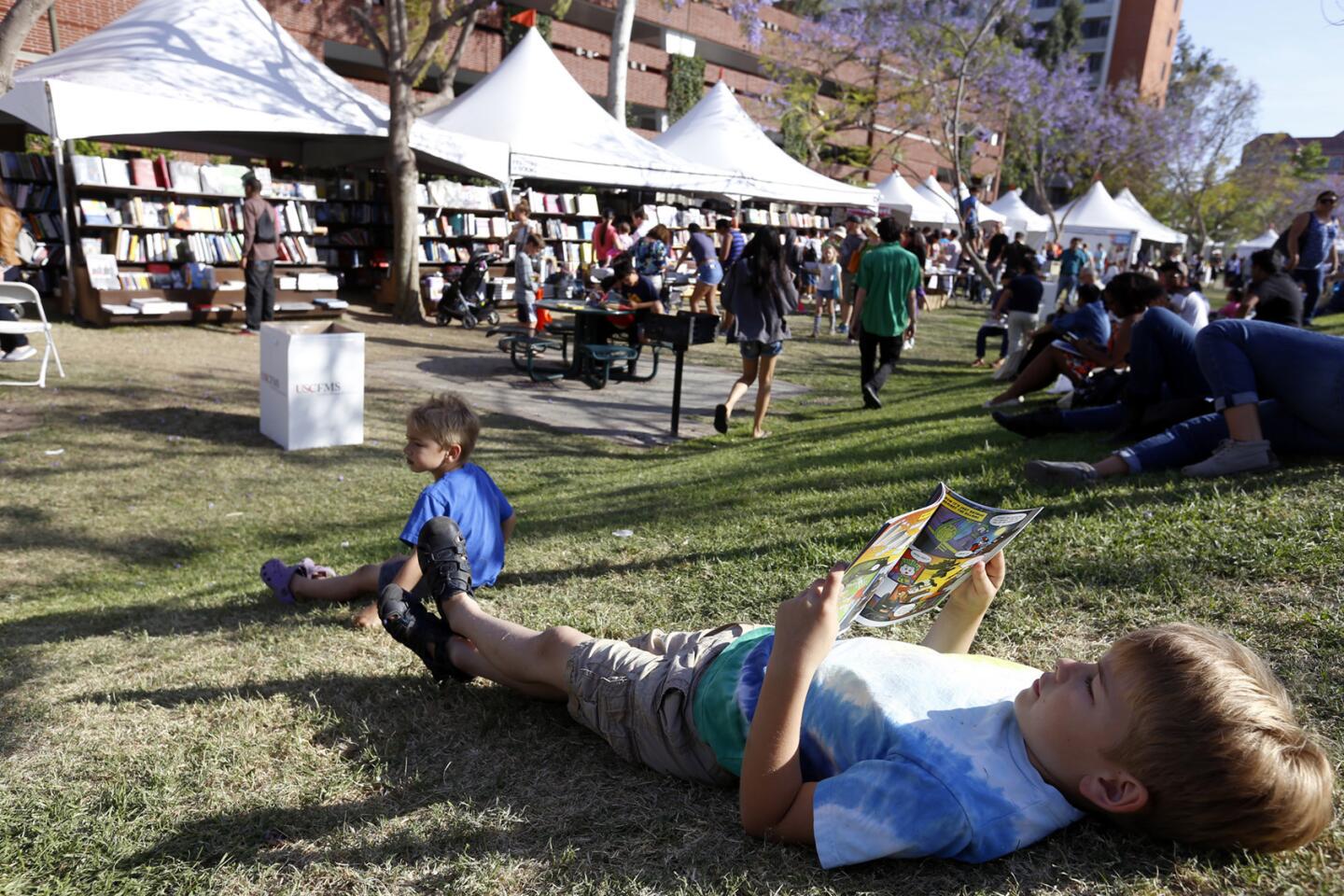

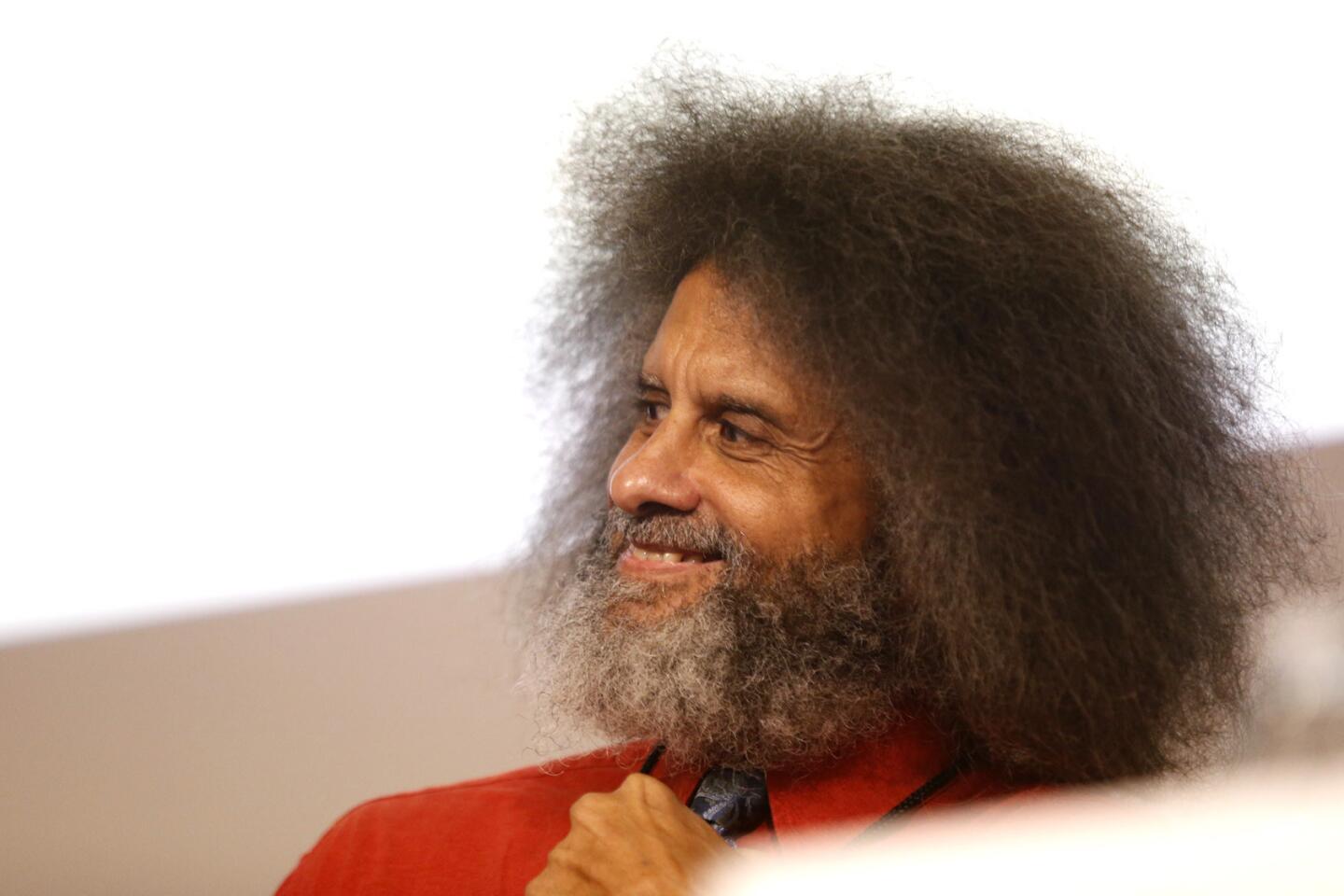

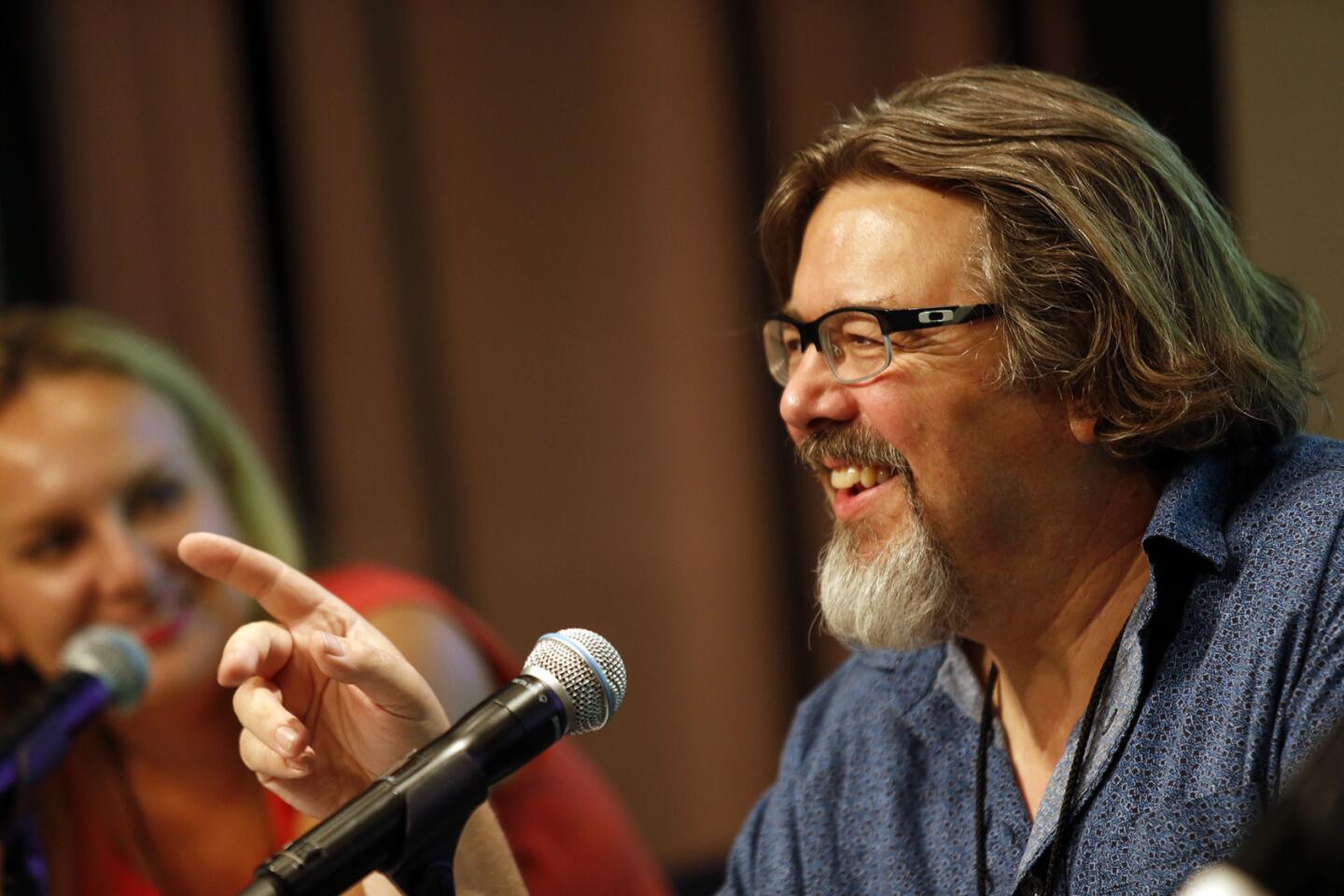

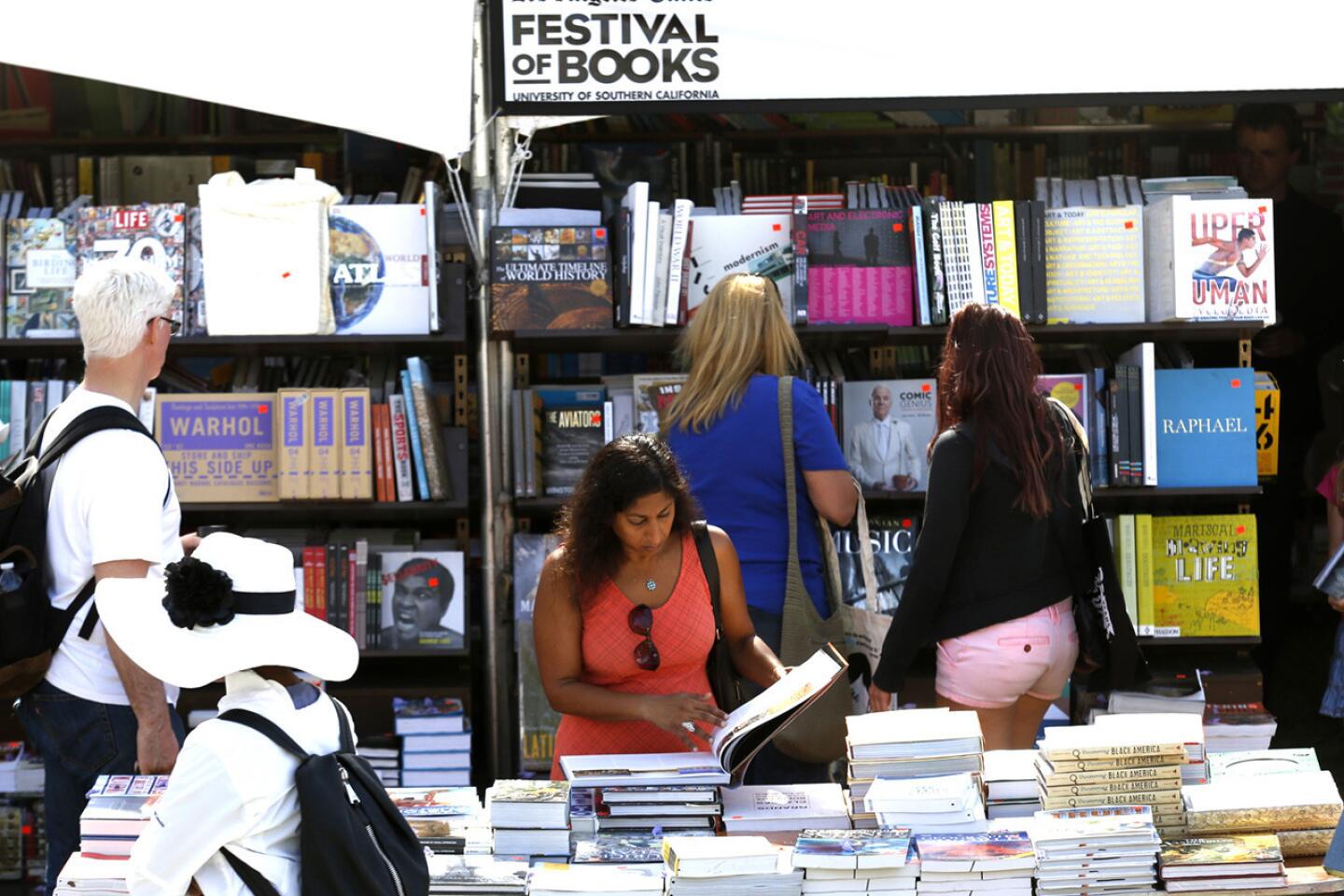

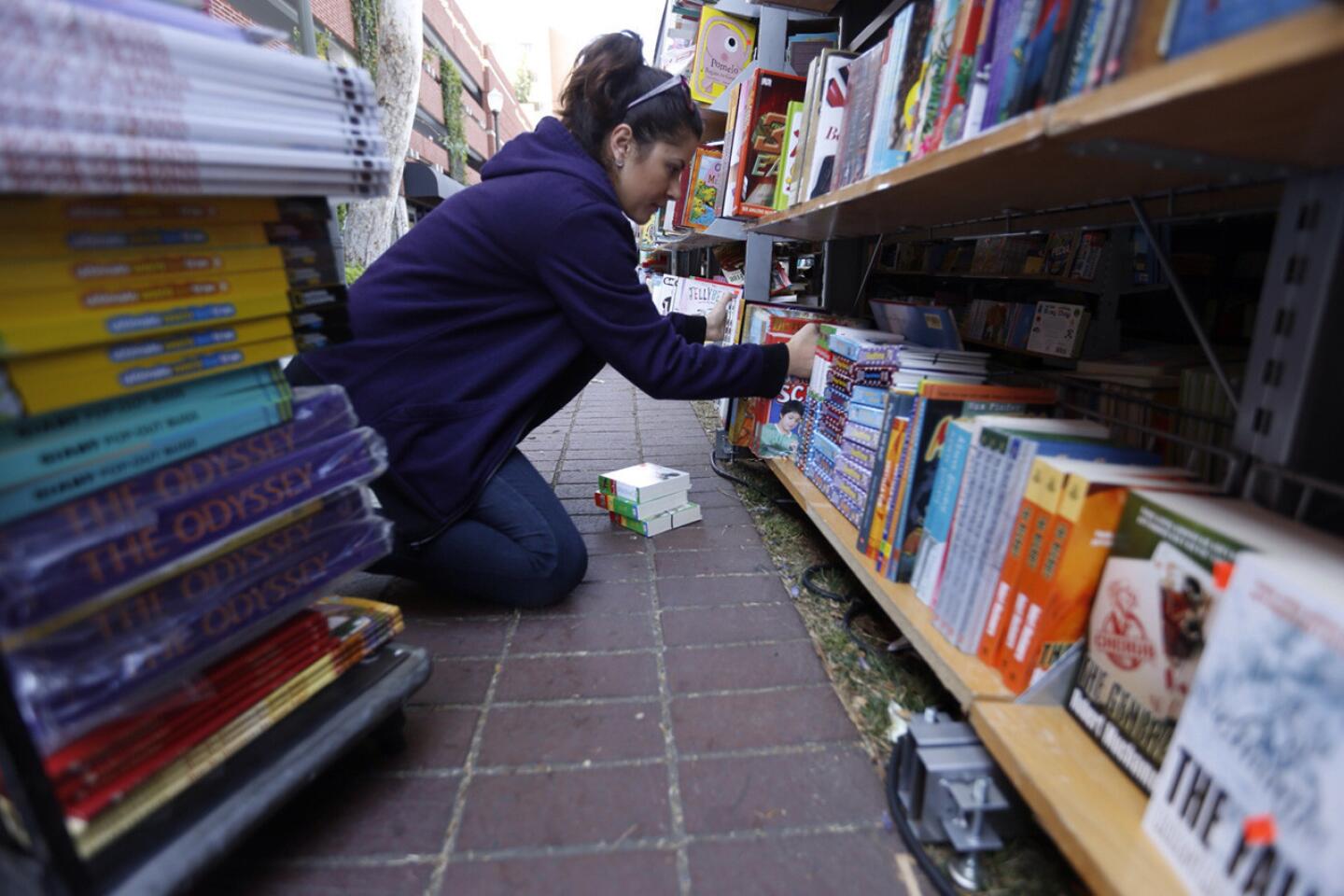

In a conversation Sunday at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, author Josh Kun and author and chef Roy Choi discussed food, politics and L.A. history while offering a fascinating, in-depth preview of the book “To Live and Dine in L.A.: Menus and the Making of the Modern City.”

Kun wrote the book, scheduled for release in June, with a foreword by Kogi BBQ king Choi.

“Menus are social text. They’re urban text. They’re pieces of fiction. And they are written,” said Kun, an author, journalist, critic and professor at USC.

FULL COVERAGE: FESTIVAL OF BOOKS

Kun spent two years diving into the Los Angeles Public Library’s archive of local menus, which dates to the 1800s. Choi joined him in his extensive research, signing on as a “spiritual guide.”

“I knew this project was amazing when we got access to the rare book vault and looked at those menus. It was like a time portal,” he said.

“How can we look at our city and its history through the window of menus? Through the menus, how can we see what was missing?” he asked.

#LITIDOL: AUTHORS DISCUSS THEIR LITERARY IDOLS

Choi pointed out the prevalence of fancy banquet menus in the 19th century that were rich with heavy cream. (“I really like the idea of heavy cream as a symbol of racial hierarchy in Los Angeles. I’m gonna steal that,” Kun joked.) “It made me think there must’ve been more food in Los Angeles than opulent banquets.”

Kun and Choi discussed the evolution of the book, which went from coffee table material to an in-depth examination of menus and their place in the complex fabric of our city’s history and our ongoing societal issues.

(“You thought it was just gonna be heavy cream, but it got heavy instead,” Choi said, laughing. “That’s real.”)

“We’ve got about 25,000 places to eat in L.A., but we are the ‘epicenter of hunger,’ according to the USDA,” Kun said. “We live in both a foodie society and a food bank society. How do you reconcile those two things? How can restaurants and food be used to restore ideas around justice, around community and equality?”

Choi’s own career has reflected a pervasive concern with the importance of food to community, and the importance of community to food.

He spoke of Kogi’s role in the popularization of food trucks, taco trucks in particular.

“A lot of people weren’t really experiencing taco trucks. They only saw them as things on construction sites, as nuisances, as dirty,” he said. “But when we came out, it was like the book fair came to town. Everyone was happy. There were no limits. Parking lots became auditoriums. People you thought were scary were not scary, just there to get a burrito and two short rib tacos.”

He also discussed his forays into Chinatown and Koreatown, where his Mid-Wilshire restaurant POT presented a distinct challenge.

“We have a little bit of a divide, whether you’re Chicano, Korean American, Cambodian American, whatever. There’s this kind of double life of home life, outside life, not being able to express your identity in a succinct way. So POT was kind of our exploration of that. Let’s put ourselves in the epicenter of Koreatown, but let’s not be a Korean restaurant; let’s be a Korean American restaurant.”

His next major project will bring his sensibilities to Watts, where he was approached about opening his own version of a fast-food restaurant.

“We’re just trying to stretch the boundaries of what our brains think is normal and ask questions. Why do we have these divides between access to food? Who gets to eat certain types of food?” he said of the thinking behind Loco’L. “What if we just cook for you?”

Loco’L is tentatively set for a September opening, across the street from the Jordan Downs housing projects.

Choi also spoke of his collaboration with downtown’s 3 Worlds Cafe, which he described as “a small project, but a big project at heart.”

It’s a functioning cafe that also provides a work-study program for students at Jefferson High School. Many of the research meetings for “To Live and Dine in L.A.” were conducted there.

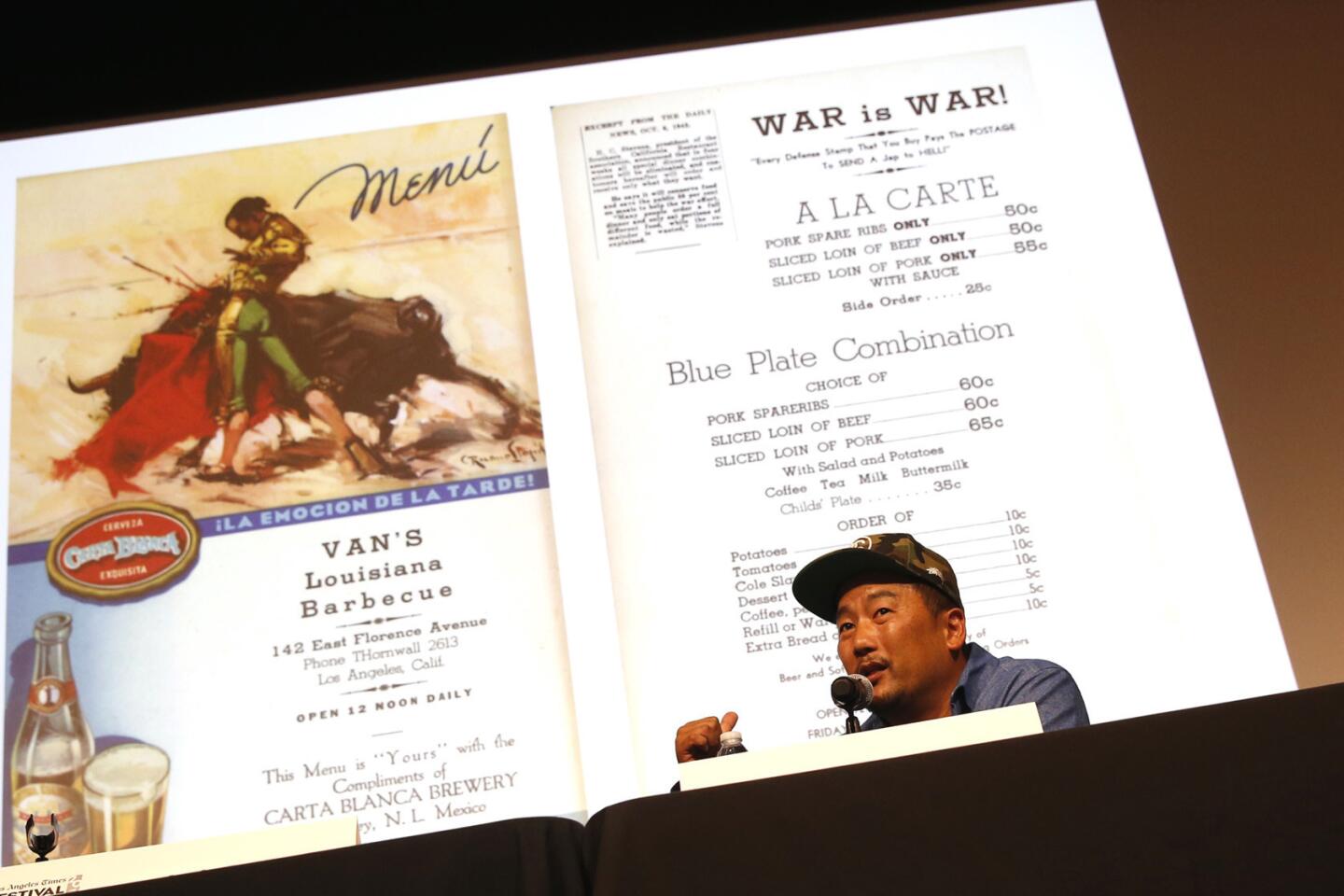

Kun and Choi shared some of their choice findings in a slide show, illustrating just how telling a menu can be.

“You can find information about food rationing through menus,” Kun noted.

Kun and Choi reflected on Los Angeles’s pre-World War II farm-to-table cuisine, on lunch counters, and on the rise of car culture reflected in drive-in restaurants; Kun even showed Choi one of his predecessors, a late-19th century cart that peddled oysters across downtown.

“It was really interesting to see how these food systems change over time,” he said.

Of course, not all menus are even written down, and Kun and Choi noted their absence.

“How can we stand up for all of that culture and life, especially the immigrant cultures where menus aren’t written?” Choi wondered. “That’s food too. That’s L.A. culture. That’s L.A. history. Sometimes menus are written on a cardboard box the produce came in, then thrown away. Our city lives and breathes outside of the menu as it does inside.”

MORE FROM THE FESTIVAL OF BOOKS:

Why Claudia Rankine’s book on racism has no ending

How actor Jason Segel rescued his own ‘Nightmares!’

Producer Brian Grazer’s advice for success -- create ideas

Follow the books section on Twitter @latimesbooks and Facebook

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.