Emotions set Ralph Lemon aloft

- Share via

Reporting from New York — — Choreographer Ralph Lemon begins performances of his complex “How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere?” by showing a film called “Sunshine Room,” which he made to explain his preoccupations over the last few years. It serves as the work’s opening and as an introduction to the sequences that follow. But he doesn’t simply screen it. He takes a seat on the stage as it’s projected and makes comments as it proceeds. He tells the audience that his most significant experience was befriending Walter Carter, a former sharecropper born in 1908, while doing research in Mississippi.

FOR THE RECORD:

Ralph Lemon/Cross Performance: An article Nov. 7 about choreographer Ralph Lemon and his company Cross Performance incorrectly said that actor-dancer Okwui Okpokwasili was married to dancer David Thomson. —

In this indirect fashion, Lemon gracefully begins the unconventional and tumultuous work, sharing his world unashamedly. That world has recently been devastated by the deaths of Carter and of Lemon’s partner, dancer Asako Takami. “I created it as I came back into art making,” Lemon says. “I was all emotion, and when I am all emotion, the body disappears. Emotions became my material.”

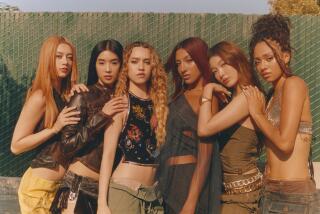

Along the way, many things happen in “How Can You Stay in the House,” which will be performed at REDCAT in downtown L.A. five times this week. In “Sunshine Room,” Lemon features a scene in which Carter demonstrates the two-step, his face flooding with memories — “I’ve never met someone so alive,” he says — and he reveals his feelings as he and Takami, who was fading with cancer, watched Andrei Tarkovsky’s brooding sci-fi film “Solaris” from 1972. After the video introduction, his six dynamic performers dance wildly to the point of exhaustion, one sobs uncontrollably off- and onstage, projections of ghostly white animals cavort on a backdrop, and in another sequence, nothing happens, and then Lemon dances a duet. Though there is disjointed, random movement, this work is not really dance. Right now, conventional forms don’t serve his aesthetic purpose.

In late August, a couple of weeks before the work’s premiere at Krannert Center for the Performing Arts at the University of Illinois, Lemon discussed his work in the quiet of the cafe at the Rubin Museum of Art in Chelsea. Elegant and boyish-looking at 58, he builds his pieces one upon the other, each an outgrowth of those that preceded it. Over long periods, he maps and archives his material, including conversations, writings, drawings and films improvisations, as well as documenting everything in videos.

By disbanding his 10-year-old Ralph Lemon Dance company in 1995, Lemon freed himself to spend lengthy periods of time traveling the world, researching and developing large-scale, ambitious projects. Calling his company Cross Performance, he assembles a team of collaborating artists for each work. “How Can You Stay in the House” grew out of “Come Home Charley Patton,” from 2004, the third part of the “Geography” trilogy, which was an exploration of race and the illusion of freedom. He met Carter in the Mississippi Delta while seeking out descendants of great country-blues musicians in the South for “Charley Patton.”

“When we ended ‘Charley Patton,’” he says, “it felt like a liberation.

“But after a while, I didn’t feel it was finished. Life and art got all mixed up. I called the performers and asked if they’d come back and continue.” He started them off with the closing dance of “Charley Patton,” asking them to improvise from there for “How Can You Stay in the House” He didn’t want anything to look composed. He asked them instead to just move randomly until they couldn’t move anymore. “I wanted it to be relentless and chaotic,” he says. “To be a challenge for audiences, irritate them, so they’d want to stop it.” (In fact, in some performances, people have walked out.) Lemon’s performers thrive on his methods. “Ralph’s an amazing artist,” says Okwui Okpokwasili, an actor and dancer with Cross Performance. “He begins with a question and then waits to see how we answer it. He’s very, very curious. He’s also very loving. When he asked us to do the ecstatic dance, he made sure we wanted to do it. After all, he really wants us to blow our insides out, from our bellies to our heads. He wants to show joy in the struggle.”

She is the dancer who sobs in the piece. “Ralph came into the studio two months after Asako passed away,” she says. “When he started talking, he just couldn’t stop crying. He asked me, ‘Could you do this?,’ meaning be a proxy for him and shed his tears in the performance. I agreed to try. He gave me films of professional mourners to study, but it’s my little secret how I do it night after night. All I can say is that I go through rituals to prepare.”

Her husband, dancer David Thomson, shares her respect for Lemon. “Ralph’s work is incredibly difficult,” he says. “If you think about it before you do it, you’re screwed. He forces you to live in the moment. His dances aren’t about being beautiful but about being real. Some people are repelled by it — it’s too much for them. He pushes those responses. It’s a crazy piece is what it is. I call him a 360-degree artist because he brings in writing, visual elements and movement. He’s not locked into any one identity.”

Lemon’s background doesn’t really explain his complex and philosophic aesthetic. Born in Cincinnati and raised in Minneapolis, he studied literature and theater arts at the University of Minnesota. After a brief stint as head of his own theater company, he joined vocalist and choreographer Meredith Monk in New York, the ideal mentor for a budding interdisciplinary artist. In 1985, he founded his company and started experimenting.

He came up with the title “How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere?” when he was doing research in Chicago. While teaching middle-school students, he suggested that they investigate their backgrounds through family mementoes and on the Internet. One girl stayed inside 12 hours on the project, prompting a classmate to ask the title’s question.

Lemon may have also asked himself the question in relation to the work, for so much of what went into its creation is barely seen or alluded to, the results infinitely subtle. “I had to find the balance between what I need and what the audience could accept,” he says. “I couldn’t know if they’d accept the furious emotions expressed on stage. But I didn’t want to make them friendlier either. The work has helped me. I wouldn’t use the word ‘heal’; it’s more complex than that.”

After this? “I can’t imagine,” he says. “I think of myself as a receiver so I can wait. That’s what’s gone on in the past. Things have happened to me. I’ve put the pieces together as they came into my life.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.