Some homeowners facing the prospect of repeated foreclosures

- Share via

Every morning at 6 a.m., Brenda Duchemin kneels down on two plush throw pillows in front of a carved teak shrine in her Diamond Bar home and chants.

In front of a cluster of oranges, a small teacup and a golden lotus flower on the shrine, the slight 53-year-old tries to expel the negative images: the two homes she and her husband, Mohammad Ashraf, lost to foreclosure auctions last month, the bankruptcy petition they were forced to file in 2009, and their ongoing battle to stay in their spacious and airy home, which is furnished with soft blankets, leather couches and Elvis commemorative plates on the walls.

Daily chanting helps her karma, Duchemin says, which is currently not in such a good state.

“We don’t know what we did in a past life to bring this out,” she said, a slight Boston accent tinting her speech. “I must have been a horrendous person down the line.”

Though signs of recovery in the housing market are emerging, thousands of people throughout the Southland are still in a precarious position on the brink of foreclosure, struggling with monthly bills and mortgage payments.

Duchemin and Ashraf are an extreme example because they’ve gone through foreclosures on two homes and are in danger of losing a third. They aren’t alone: Flimsy lending practices mean that thousands of other borrowers face the prospect of repeated foreclosures, mortgage and foreclosure experts said.

The problem is especially visible in areas that attracted speculative buyers during the boom. In Maricopa County in Arizona, which includes Phoenix, at least 283 individuals have received a foreclosure notice on two or more properties since 2006, according to data provided by RealtyTrac Inc.

Multiple foreclosures are “probably more common in this decade than they’ve ever been because everyone was running to get into the real estate investing business,” said Rick Sharga, a senior vice president at RealtyTrac.

Clark County in Nevada, another area that attracted house flippers, had at least 179 buyers who were foreclosed on more than once over the same period, the data show.

A RealtyTrac spokesman said the actual numbers were probably larger than the estimates provided, because some of the data were private. The search only looked at multiple foreclosures within the seven counties that the firm studied -- Maricopa, Clark, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego.

“It wasn’t unusual to allow folks to buy not only two homes but three, four or five,” said Sean O’Toole, founder of data-tracking firm ForeclosureRadar.

Because people thought the price of real estate would keep climbing, O’Toole said, they figured that the more homes they bought, the more they’d earn eventually.

“In a lot of cases, you had folks in this gold rush mentality: ‘Real estate is going up, the more houses I buy, the more money I’ll make.’ ”

The practice appears to have been less common in areas with higher prices and fewer speculative buyers. Los Angeles County, where Duchemin and Ashraf live, had just 135 people with multiple foreclosures, despite having significantly more foreclosures overall than Maricopa or Clark counties.

Duchemin and Ashraf say they are anything but flippers. Had not both their health and the economy taken bad turns, they say, their finances would have been able to support their real estate investments.

The couple bought their Diamond Bar house for $550,000 in 2006, hoping to finance the purchase by selling their town home in Brea -- a sale that never materialized, they say, because of the housing crash. The year before, they’d also bought a $340,000 home in Las Vegas as a retirement property, which they rented to a tenant until last year. At the time of the purchases, their only sources of income were workers’ compensation insurance payments and Social Security, but that wasn’t a problem for the lender.

“We don’t know how much longer we can keep going,” Duchemin said, stroking their white Maltipoo, Sugar, one of four dogs the couple keep segregated in various areas of their house because the pets fight.

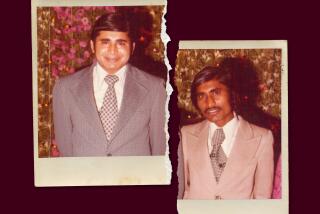

Ashraf, a warehouse supervisor, was injured in 2003 and had to have three discs replaced in his back. The surgery went poorly: He was in the intensive care unit for six days and had a stroke during that time. He now takes fistfuls of medicine each day, and has been even more subdued since his father died in Pakistan in 2008.

Duchemin was hit by an 18-wheeler truck in 1994 and has suffered severe seizures since then, although she had a device inserted in her chest to stem the seizures.

Ashraf is just a shell of the man he once was, Duchemin says. “This is a man who took pride in supporting me, making me feel like I was a queen -- he was one of the strongest men I ever met,” said Duchemin, who has voluminous brown hair and carefully sculpted eyebrows. “To see him go from that to an invalid. . . . “ she said, trailing off.

Ashraf’s workers’ comp payments were cut in half in 2008, hampering the couple’s ability to pay any of their three mortgages.

Duchemin, who has worked as a teacher’s assistant, a marketer for a chiropractic office and a locksmith, among other things, started looking for work last year but hasn’t had any luck. Now she’s applying for jobs that a high school student would be overqualified for, she says.

She’s tired of hearing people say the economic downturn is ending. “There is no recovery,” she said.

Though they were heartened by the news that the government was trying to help homeowners, the couple doesn’t have much hope for mortgage help. They informed Washington Mutual in March 2008 that they were in trouble and asked for a modification on the Diamond Bar home, but tried to pay the mortgages on all three of their houses, missing a payment here, a payment there.

They eventually lost the Brea town house and Las Vegas home to foreclosure, and both properties went up for auction last month.

Duchemin and Ashraf say they are doing everything they can to keep their Diamond Bar house.

They filed for bankruptcy protection in July in the hope that it would enable them to keep the house. They’ve been to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Los Angeles three times since October to get their bankruptcy confirmed, but each time a problem has arisen. The next date is Monday.

To keep making payments on their home, they sold their Toyota Tacoma and family jewelry, including a gold anchor necklace Ashraf had since he served in the merchant marine. They canceled every service they could except for the Internet, which allows Ashraf to keep in touch with his family in Pakistan.

Duchemin rides her bike everywhere to save money on gas -- when she goes out. Mostly they stay at home, worrying that the water or electricity will be turned off soon.

If they are forced to move, the two don’t know where they’ll come up with a deposit for a new place -- filing for bankruptcy has ruined their credit.

“We can’t afford to stay in our home, but we can’t afford to move,” Duchemin said.

They’re entrenched for now: Board games are stacked up on tables, crystal figurines shine on display in a case, and the four bedrooms are packed full of stuff, including Duchemin’s artwork and teddy bears bigger than a toddler.

But every day finds them on edge, waiting to see what happens next. They spend their days trying to appreciate the home they love, with its hand-laid brick walkway, fig and lemon trees in the yard and “Wizard of Oz” paintings on the walls, wondering what went wrong.

“I can’t provide the way I used to provide everything for. . . . Excuse me,” Ashraf said, breaking down. “For my family,” he continued. “And I just -- at this point, I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

alana.semuels@

latimes.com

Times photographer Robert Gauthier contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.