Museum pieces are sure to be well read

- Share via

CINCINNATI -- An old brick building just north of downtown Cincinnati gives little hint outside of the treasury of nostalgic icons within its walls.

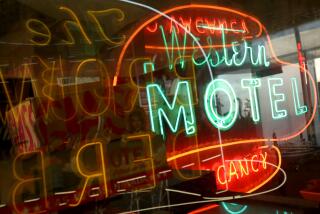

Some unlighted motel and restaurant signs line the nearby street, and a 20-foot fiberglass genie that advertised the Aladdin Carpeteria carpet cleaning company in 1960s Los Angeles looms near the door. But that doesn’t prepare visitors for the burst of color, motion and memories greeting them inside the American Sign Museum.

A tour of the more than 200 signs and other items that include sign makers’ tools is a journey through decades of America’s evolving cultural taste, technology and commercial design -- at times evoking fond remembrances of family road trips.

Vivid pinks, greens and other hues light up the foyer that museum founder and President Tod Swormstedt calls his “Sign Garden” -- the appetizer for a sign smorgasbord spanning the late 1800s to the 1970s.

Visitors entering the garden are drawn to a spinning Sputnik replica that welcomed customers in the 1960s to the Satellite Shopland shopping center in Anaheim. The 6-foot-diameter plastic globe -- its metal spikes studded with colored light bulbs -- spins near a Dutch Boys Donuts windmill with rotating blue neon blades from 1950s Denver.

Nearby is the multicolored 1950s SkyVu Motel sign that stood along state Route 40 just outside Kansas City, Mo., beckoning travelers with light bulbs flashing on and off in sequence as though traveling around the sign. There’s also a 1930s United Pentecostal Church sign from Shreveport, La., with its streamlined design and a 1960s Howard Johnson sign from New York’s Times Square.

Nostalgia is a key attraction -- especially for baby boomers who grew up in the post-World War II years when Americans began taking to the roads for family vacations.

Neon signs from the 1920s through the 1960s are particularly eye-catching, along with elegant hand-painted gold leaf on glass from the late 1800s and 1900s and the first electric signs of the early 1900s -- porcelain-enamel illuminated with light bulbs. Plastic signs that emerged after World War II, hand-lettered show cards advertising Las Vegas casino entertainment and sign salesmen’s samples also are featured.

John Jakle, co-author of several books on American roadside history and a professor emeritus of geography and landscape architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is a fan.

“With the quality of the signs and the depth of understanding and knowledge in the interpretation, it really is a national treasure,” Jakle said. “Roadside America is very short-lived, and about the only way Americans are going to be able to remember important eras in landscape history is through museums like this one.”

Swormstedt, who spent 26 years working at the Sign of the Times industry trade journal, started his “mid-life crisis project” in 1999.

He considered other cities before choosing Cincinnati, where his family has published the trade journal since the early 1900s. The journal’s ST Media Group International Inc. parent company has contributed $1.5 million for the not-for-profit museum that opened in 2005.

He has traveled thousands of miles and spent innumerable hours on the Internet assembling the growing collection that also includes about 300 signs awaiting display, 800 books and catalogs, and more than 1,200 photos and slides.

Signs are donated and purchased. Swormstedt hears about them from sign companies and from people seeing the website or reports of his sign rescues. He also attends swap meets for gas station memorabilia collectors and shows featuring antique advertising.

“Most museums start with a collection, but I started without a single sign,” he said.

The museum’s first piece was a box of gold leaf samples on glass created by noted gold leaf artist Raymond LeBlanc. The first sign Swormstedt acquired was an animated neon welder’s sign, but it wasn’t in good condition. He traded it for several others, including a three-dimensional neon mortar-and-pestle sign now mounted atop the museum’s late-1930s corner drugstore display.

About 2,000 people visit annually. The response has been good enough that the museum will open in a new site late this year or in early 2009. The new property will more than triple the current space and provide 28-foot-high ceilings to accommodate larger signs.

Visitors discover the museum in various ways, including its website and other roadside Americana related sites. Swormstedt also gets calls every time the museum’s rescue of an old sign is reported. The most challenging rescue was of an Indiana barn wall advertising Mail Pouch chewing tobacco. It took nine people a day to get it down and across a creek with a washed-out bridge.

Swormstedt enthusiastically guides visitors on the 1 1/2- to two-hour tour past exhibits including a gas station sign and two pumps from the 1930s, and vintage storefronts filled with pre-neon, neon and post-neon signs.

“I guess signs are in my blood or genes,” he jokes.

He stresses the importance of preserving older signs before they disappear as a permanent record of the sign industry’s history and its contributions to commerce and the American landscape.

“Many of these animated neon signs would be outlawed today,” Swormstedt said, pointing to the rotating 6-foot-diameter metal world globe encircled by a Saturn-like ring of neon cars that advertised a 1950s auto painting company in Compton.

Many cities banning flashing, animated signs don’t believe they fit in aesthetically with urban redevelopment, and some suggest they distract drivers.

But it’s those flashy neon emblems that especially fascinate museum visitors.

They bring a smile to your face.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.