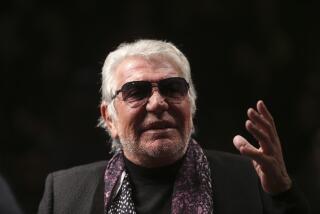

Oleg Cassini, 92; Designed an Elegant American Look

- Share via

Oleg Cassini, the son of Russian aristocrats who became a savvy influence in the world of fashion and helped define the style of Jacqueline Kennedy, has died.

Cassini died of still undisclosed causes at 92 on Long Island.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. March 19, 2006 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Sunday March 19, 2006 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 44 words Type of Material: Correction

Oleg Cassini obituary -- In some editions of Saturday’s Times the obituary of Oleg Cassini did not say when he died. Cassini died Friday in a Long Island hospital. He was 92. The article also did not include his wife, Marianne, among the survivors.

As famous for his colorful lifestyle as he was for his clothes, Cassini was married to Hollywood star Gene Tierney and engaged to Grace Kelly -- before she became a princess. As “secretary of style” to the most stylish first lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, Cassini foreshadowed a time when designers would be defined by their celebrity clients.

As a businessman, Cassini was an innovative leader in the fashion industry. He was the first to understand the power of franchising his name, with as many as 50 licenses, including sunglasses, watches and children’s clothes. (At one time, Cassini estimated an annual worldwide retail volume of $400 million.)

He bucked fashion tradition by refusing to show with other designers during the New York seasons, instead taking his designs directly to the public, exhibiting his collections in stores across the country and becoming a regular television guest on “The Tonight Show” and “The Mike Douglas Show.”

He understood there was wealth to be had in ready-to-wear instead of high fashion. He was the first to introduce brightly colored shirts for men and was responsible for the short-lived trend of the Nehru jacket. He popularized the pillbox hat as an accommodation to Kennedy’s newly acquired bouffant hairdo.

In spite of all this, he struggled for many years to prove he was not just a playboy dilettante but indeed a serious fashion player.

Ironically, by dressing the first lady, the immigrant galvanized an American fashion sensibility. As the world took its cues from European designers, Cassini offered an elegant new way to be classically American. He took conservative staples, such as the shirt dress, the simple shift and the wool coat, and made them into new American classics. And he made them sexy. The woman wore the clothes, the clothes did not wear the woman.

But Cassini’s reputation as bon vivant and man about town overshadowed his credibility as a serious designer. This was unfortunate, because he never got much credit among the fashion industry, said Edie Locke, president of the Los Angeles branch of the Fashion Assn. “One thought ‘celebrity’ before taking him very seriously as a designer, which probably was not justified. It wasn’t the way that you think of a Calvin [Klein] or a Donna [Karan],” said Locke, who was editor in chief of Mademoiselle magazine through the 1970s.

Cassini seemed destined to lead a fast life, from his beginnings as the son of the Countess Marguerite Cassini, daughter of a Russian ambassador to the United States, and Alexander Loiewski, a Russian diplomat. In 1917 when the Czarist government was overthrown, the family fled, first to Denmark and then to Florence, Italy, where they settled and Marguerite opened a dress shop.

Cassini studied art and opened a tiny salon, getting orders from the European aristocracy and American debutantes, whom he did his best to introduce to the ways of romance, as he tactfully noted in his 1987 autobiography, “In My Own Fashion.”

He came to New York in 1936 and was soon joined by his brother Igor, who went on to fashion a career as the Hearst newspaper gossip columnist Cholly Knickerbocker. The brothers found joblessness and near poverty but, armed with good tuxedos and European manners, they eventually made their way into East Coast society.

Cassini was briefly and disastrously married to cough syrup heiress Merry Fahrney, becoming the fourth of her nine ex-husbands.

After the divorce and scandalous routing by gossip columnists (“the naughty count” and “international itinerant”), Cassini moved to Hollywood in 1940, where he worked at first in the costume department of Paramount Studios and later Twentieth Century Fox.

He designed costumes for Veronica Lake, Marilyn Monroe and Gene Tierney, whom he married in 1941. The couple enjoyed life in Hollywood circles. He gave up his title as a count to become a U.S. citizen and enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II, serving stateside.

But the Hollywood high life would end with the birth of the Cassinis’ first child, Daria. When Tierney was pregnant, she was exposed to rubella by an overzealous fan. Daria was born blind and severely retarded, a devastating blow to the couple. Cassini later wrote that he had fantasies about killing himself and his daughter. Tierney plummeted into a deep depression, which she battled for the rest of her life. She divorced Cassini in 1947, but they reconciled and had a second daughter, Christina. The couple divorced a second time in 1952. Still, even after she remarried, they remained friends until the actress’ death from emphysema in 1991.

Cassini never remarried, but his name was linked to a number of beautiful women, including Anita Ekberg, Linda Evans, Jill St. John and dozens of models.

Perhaps the most famous name of all was actress Grace Kelly, to whom he was unofficially engaged for two years. Her family opposed the courtship because he was divorced. Kelly unceremoniously announced to Cassini that their relationship was over because she was going to marry Prince Rainier of Monaco.

In spite of the heady social life, Cassini was determined to become a successful fashion designer. Ignoring Tierney’s protests, he returned to New York in 1950 to open his own fashion house. But it wasn’t until a newly elected John F. Kennedy asked him to be the official designer for his wife that he achieved his greatest success. Kennedy’s father, Joseph, picked up the tab for the nearly 300 outfits designed for the first lady in her 1,000 days of office.

A series of letters between the designer and first lady were chronicled in his 1995 book “Oleg Cassini: A Thousand Days of Magic.”

Cassini’s days as a movie costume designer proved valuable as he and the first lady agreed she should dress for the role and not for herself. The letters show the details both of them paid attention to: She should wear a cloth coat to the inauguration so as not to look as matronly as previous first ladies. She should show cleavage, but not too much.

Years later, fashion runways still pay homage to the simple coats, A-line dresses and pillbox hats favored by Jacqueline Kennedy.

After President Kennedy’s assassination, Cassini and the first lady parted ways, but the designer’s name was imprinted in the American consciousness. He had, by then, also become a full-fledged member of what brother Igor had named “the jet set.”

Cassini continued to live and love well, but like many aging playboys, he saw the errors of his ways, not in romancing, but in promoting the use of fur. He blamed himself for the death of 250,000 leopards that were killed as women flocked to copy a coat he had designed for Mrs. Kennedy. “After that I said, ‘I will do my best to redeem myself,’ ” he told The Times.

“St. Francis of Assisi has always been an inspiration to me,” Cassini had said. “He was a playboy, too.”

Cassini became an animal activist, earning wide praise from animal rights groups. His last great project was introducing micro-fiber fake furs in 1999.

Cassini lived in Gramercy Park in New York City with a menagerie of animals. He is survived by his daughters and grandchildren. His brother, Igor, died in 2002.