Grizzled Veterans

- Share via

It’s happening again.

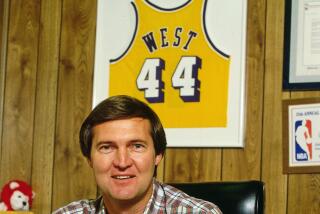

It was always this way with Jerry West, the fear, the worry and, worst of all, the glory.

Of course, he says it’s different in his new incarnation as general manager of a team called the Grizzlies, located in Memphis, Tenn., a town on the banks of the Mississippi that meant a lot more to music than it ever meant to basketball before he arrived.

In his old incarnation, of course, he was the living embodiment of the fabled Laker organization, the symbol on the NBA logo and the toast of Los Angeles, but this is better, he says.

“It was the best thing I’d ever done in my life, leaving at the time I left,” West said last week from Memphis. “And I think the second-best thing I did was come here.”

Some things are hard to change. West’s Laker career was glorious, however nerve-wracking, and so is his Grizzly career.

On his way out of Los Angeles, West changed the face of the NBA and set the franchise atop it for years to come, turning Showtime into the Shaquille O’Neal-Kobe Bryant Lakers, so that one dynasty almost ran into the next.

The job West has done in Memphis was even more improbable because he wasn’t working with the same resources, or many resources at all.

Grizzly tradition was Laker tradition upside down, the franchise record for wins after seven seasons in the league standing at 23.

They were already on their second city, having started in Vancouver, but free agents weren’t exactly tripping over themselves to move to Memphis so they could see Graceland.

Not that it mattered what free agents thought of them, because the Grizzlies had no room to maneuver under the salary cap. Owner Michael Heisley had taken care of that by signing guards Jason Williams and Michael Dickerson to $50-million contracts, reportedly without consulting his general manager at the time, Dick Versace.

Williams was wild and Dickerson played only 10 more games before an injury forced him to retire.

If West knew what he was getting into, more or less, when he un-retired in 2002, and if he was upbeat most of the time, he was -- as usual -- of two minds, at least.

“After watching for about a month,” West recalled, “not even a month, after watching training camp and some exhibitions, I said, ‘What did I get myself into?’ ”

None of his Laker teams ever started 0-9, but his Grizzlies did. West then fired Sidney Lowe, the coach he’d inherited and, in a move that stunned everyone, hired Hubie Brown, then 69, the old fire-breathing dragon from the ‘80s, who’d been far out of the loop, doing TV since the New York Knicks fired him 17 years before.

What ensued was one of the most amazing turnarounds in NBA history. The Grizzlies started 2-9 under Brown, while the players got used to the new decibel level, and finished 26-36.

If this seemed like remarkable progress, it was nothing compared to this season when they went 50-32, broke the franchise record for wins -- on Feb. 6 -- and made the playoffs, in which they now trail San Antonio, two games to none.

This wasn’t just Old School. These are postgraduate studies and the geezers who did it aren’t merely happy. Brown says it’s “overwhelming.” West calls it “a magical year.”

Of course, the magical times were always the weird ones for West, who preferred the quest. When the Grizzlies took off this season, he began going through changes. When a Memphis Commercial Appeal reporter did a story about how long Brown might coach, West went weeks without returning his calls.

It’s still the Jerry West the Lakers knew, in Grizzly fur and, on balance, happy as he can be.

He’s at the halfway point of his four-year deal. He just hopes he can last the last two.

His Way or the Highway

Not that the hiring was a surprise, but when a friend told center Lorenzen Wright that Brown was the new coach, he couldn’t believe it.

“I said ‘No, it can’t be, he’s a sports announcer, so it’s not him,’ ” Wright said. “ ‘Let me find out the name, who it really is.’

“We got to practice the next day, it really was him.”

Of course, Wright was 11 the last time Brown had coached anyone, but he was a coach, all right, the old-fashioned kind, a coach’s coach whose clinics were famous, and whose only problem was the players.

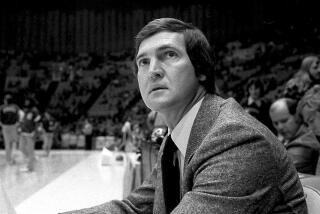

He was a new breed in the NBA when he arrived in Atlanta in 1976, the first of the so-called “Five-Star guys,” so named because they worked at the Five-Star summer camp for high school players in Honesdale, Pa., a mecca for young coaches.

Five-Star guys such as Brown, Chuck Daly, Mike Fratello, Brian Hill and Brendan Malone came up the slow way, through suburban high schools and little colleges. They were passionate, hard-driving workaholics. None more than Brown.

His NBA career would be characterized by dramatic turnarounds and quick exits, his ability limited by how little time it took him to wear out his team and his welcome.

In four seasons in Atlanta, he took a Hawk team that had gone 29-53 before he arrived to 50 wins. In the fifth season, he was fired.

He then took a 33-win Knick team to 47 wins in two seasons, only to see it fall apart after Bernard King blew out a knee, and was fired in his fifth year.

Brown was 52 and at a crossroads. Unlike his peers, who would have coached in hell if the only job open was there, he went into TV and stayed there, perhaps tired of the struggle with players.

TV was perfect for him. He could teach coast to coast, stay in the game and maintain a full schedule of clinics. The money was good; the hassle was minimal.

By his count, he turned down five chances to coach and three chances to be a general manager. It was a dream right up until Turner demoted him last season in a youth movement.

“Their format was demographics,” Brown said. “So Dick Stockton and I were reduced to part-time, the playoffs, and a smattering of games, but I was on every Thursday night in this new format in the studio.

“I said, ‘This isn’t me.’ So I called [San Antonio Coach Gregg] Popovich and he says, ‘This would be great’ and he offers me 42 games. So I now am going to do San Antonio’s games and I did three. And I was very happy doing that because I’m a game guy.

“So does this [the Memphis offer] come at the right time? Absolutely. Because for some guy to make a decision that at 69, because I have gray hair, that I can’t relate to the viewer is kind of humorous, OK? And very annoying, after 14 years of being where I was at that level at Turner and two years at CBS. All of a sudden, someone’s telling you that you can’t relate.”

West always had a keen eye for coaches, had been impressed by Brown’s intense preparation and wealth of knowledge and had asked years before if he’d ever come back.

Now, knowing what the deal was -- Brown’s son, Brendan, was a Grizzly scout -- West called and Brown said yes.

“Right time,” Brown said. “Right phone call. But more important, the right guy.”

And the environment went from gentle and forgiving to structured and demanding overnight.

“Didn’t nobody know how to take it,” Wright said. “[Brown] came in, he was yelling, he was cursing us, get to this spot, get to that spot.

“It was all for a reason. At the time, nobody knew what the reason was. And then when you get out there and start to play, you get to those spots, you have open shots. ...

“He picked out a number of games and he said, ‘OK, these games right here, we’re going to see who plays the way that I want to play.’ ”

Williams, a free spirit, was expected to be Brown’s biggest challenge, but they got along from the start.

“Well, you see, we don’t tolerate that,” Brown said. “See, we say, ‘Look, here are the rules, boom, boom, boom, boom. Now, you’ve got a style, you want to do that, whatever you want to do, that’s great -- as long as there’s not a turnover. As soon as there’s a turnover, well, now you’ve got to be accountable.’

“And that’s how we talk -- ‘So if you want to do all of that and then your butt will be on the bench in a heartbeat, that’s fine. That’s your choice.’ ”

Williams has never played better. His turnovers this season were at a career-low 1.9 a game and his shooting percentage at a career-high 40.7%.

Of course, he still isn’t much on defense and gets upset sometimes when Earl Watson, a better defender, plays in crunch time.

Mostly, it has been an idyll. Brown went to an 11-man rotation with 10 of them averaging 20 minutes and only Pau Gasol over 30, because he thought he had more depth than star power.

This was anything but the traditional approach, which is to get a great player and follow wherever he leads. Brown went to it primarily to develop players whom they might trade in two-for-one or three-for-two packages for better players.

To Brown’s surprise and everyone else’s, his players developed all the way into the playoffs, going 35-13 after Jan. 1.

That’s right, the Grizzlies in the playoffs.

“I’ve got a great three-year deal,” Brown said, “But my deal is, at the end of each year, I tell [West] whether I can go next year.”

He has never had a season like this one, so does he know if he’s coming back next season?

“No,” Brown said. “Takes a lot out of you.”

Way Out West

Takes a lot out of him?

It’s not easy being Hubie, but he ought to try spending a day as West and see how he likes it.

Brown is conventional and happy when things are going well. When West triumphs, a question occurs to him: Is this all there is?

In retrospect, West sees the summer of 1996 as the beginning of the end of his Laker days. Of course, it was the greatest summer of all, when he landed Shaquille O’Neal as a free agent, and traded for Kobe Bryant as a 17-year-old high school kid, all within eight days, from July 11-18.

Not even Red Auerbach ever pulled a caper like that. But by the end of it, West was little more than a drawl and a puddle.

That was the summer West’s secretary, Mary Lou Liebich, sometimes asked reporters if they really had to talk to Jerry that day because it might be better to call tomorrow.

Having fallen in love with Bryant in a workout, West had decided to go for both Bryant and O’Neal, sending Vlade Divac to Charlotte for Bryant’s draft rights and freeing up Divac’s $4.5-million salary to offer O’Neal.

The problem was, that still left the Lakers limited by salary cap room to a $99-million offer. With Alonzo Mourning having just gotten $105 million from the Miami Heat, O’Neal would need more than that. If Shaq said no, the Lakers, who had just traded their own center, would have a problem.

West, encouraged by owner Jerry Buss, arranged to send Anthony Peeler to Vancouver so the Grizzlies would take George Lynch’s $2.5-million salary off their cap.

Nevertheless, it was going down to the wire. West had a fallback position -- signing free agents Dikembe Mutombo and Dale Davis. Davis’ agent, Steve Kauffman, who lives in Malibu, thought they were so close, he was about to jump in his car and drive to the Laker offices in the Forum.

“The whole thing was nerve-wracking,” West said. “I talked to almost everyone in the league and, thank God, Vancouver was around.

“I said to him [O’Neal] and Leonard Armato [then his agent], ‘Look, if we can get to this number, would you come?’

“And he [O’Neal] says, I’ll never forget, and he says, ‘Yes.’

“I told him I wanted him to call our owner and tell him that because if not, I didn’t want to make the trade. And he agreed that he would do it and he left him a message, a very short message, that was extremely encouraging, so I went ahead and did it.”

O’Neal signed three days later in Atlanta, the site of the forthcoming Olympics. West and Laker lawyer Jim Persik flew in to make the deal, but Shaq was late, arriving at Armato’s hotel suite at 2:30 a.m., held up by the Olympic processing procedure.

West fidgeted the hours away, joking that if Shaq said no, he could always jump out the window.

Shaq said yes and the rest was Laker history -- as West would be too, leaving four years later with the young team in the Finals and all the heavy lifting done.

“I cared so much for that franchise,” West said. “When things were bad, I felt like I was betraying the franchise. And when things were really good, I couldn’t even enjoy that.”

Happily, the Grizzlies aren’t that far along yet.

“I can even go to the games now,” West said, “and you know what? I enjoy them.”

In his last spring as a Laker, he didn’t even watch them in the Finals. Instead, he drove around, getting scores from friends who’d call his cell phone.

One day, he said, he got as far as Santa Barbara, so even though the sun now sets into the Big Muddy instead of the blue Pacific, this is a big step for West.

*

(Begin Text of Infobox)

Breaking Through

The Grizzlies, who moved from Vancouver to Memphis for the 2001-02 season, hadn’t made the playoffs until this season (Pl-Place in Midwest Division; GB-Games behind):

*--* Season W-L Pct Pl GB 2003-04 50-32 610 4 8 2002-03 28--54 341 6 32 2001-02 23--59 280 7 35 2000-01 23--59 280 7 35 1999-00 22--60 268 7 33 1998-99 8--42 160 7 29 1997-98 19--63 232 6 43 1996-97 14--68 171 7 50 1995-96 15--67 183 7 44

*--*

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.