Even Bin Laden Has to Deal With the Mundane

- Share via

NEW YORK — He is well known as the accused mastermind of an international terrorist network dedicated to thwarting American influence in the Middle East and ruthlessly killing to advance his cause.

But testimony in a heavily guarded federal courtroom last week also paints a surprising portrait of Saudi fugitive Osama bin Laden as an organizational man beset with responsibilities ranging from real estate management to medical reimbursements.

According to the detailed accounts of Jamal Ahmed Al-Fadl, a former confidant of the Islamic extremist, running the militant group al-Qaeda (the Base) demands a broad range of skills befitting top executives of major corporations.

There are personnel files to maintain, with false names to keep sorted; diverse subsidiary businesses to run in a half-dozen countries; guest houses and farms to oversee; training exercises to organize and conduct; payrolls to meet; squabbles to settle; and hard feelings to deal with over pay and benefits.

In fact, it was over such mundane issues that al-Qaeda and Bin Laden may have suffered their most damaging breech of security.

Al-Fadl testified that it was a dispute over his own salary and festering envy over the higher pay to Egyptian terrorists that prompted him to siphon $110,000 from al-Qaeda accounts for personal investments--a transgression that led to a harsh rebuke from Bin Laden and which drove Al-Fadl into an interrogation room with eager U.S. intelligence agents.

Those sessions have provided Western counter-terrorist agents with a wealth of inside information that only now is being revealed in the trial of four men accused in the 1998 bombings of two U.S. embassies in Africa. Those blasts in Kenya and Tanzania killed 224 people and injured 4,500 others.

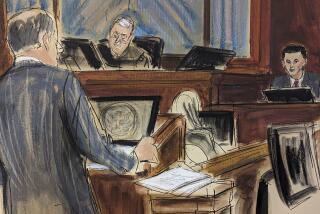

Testifying under extraordinary security in a courthouse freshly ringed by steel barriers, Al-Fadl told the jury of six men and six women about al-Qaeda’s headquarters in Khartoum. He said Bin Laden moved his operation to the Sudanese capital at the end of 1990 to be closer to the Arab world after years of operating out of Afghanistan during its war against Soviet occupation.

Empire Directed From Offices in Khartoum

Al-Qaeda opened offices on McNimr Street in Khartoum, complete with a receptionist’s area just inside the front door.

Al-Fadl said visitors were required to present an identification card to a secretary and wait until appointments were confirmed. Inside the headquarters, other secretaries toiled in a center hallway with offices on either side. Bin Laden moved into the first office on the left. But Al-Fadl said Bin Laden mostly spent time in a three-story guest house that the group owned.

“He liked to sit in the front yard and talk about jihad and about Islam and about al-Qaeda in general,” he said.

“And did Bin Laden have a specific office in the guest house?” asked Assistant U.S. Atty. Patrick J. Fitzgerald.

“Yes, in the second floor, he got big room,” Al-Fadl testified. “It’s only for him.”

In the offices on McNimr Street, members of the group were busy overseeing businesses that the terrorists purchased. These included several farms (also used for explosives and weapon training), an import-export company and an investment firm that sold produce and changed Sudanese currency into British pounds or American dollars. Al-Qaeda’s construction company built roads and a bridge in Sudan.

Such conventional businesses helped fund the budding terror organization.

In addition to their salaries, group members received fringe benefits.

Each month, bonuses in the form of sugar, tea, vegetable oil and other “stuff” were distributed “just to help them,” Al-Fadl said. In sometimes difficult-to-understand English, the former Bin Laden aide also said:

“Sometimes they busy. They can’t go shopping, and also because in Sudan [it is] sometimes hard to find sugar any time or oil and some stuff.”

And responding to prosecution questions about other support for Bin Laden followers, Al-Fadl testified:

“If somebody, the al-Qaeda member, he go to doctor or he buys his medicine and he brings a receipt, we pay him the money.”

Sometimes, bosses handed out cash bonuses.

After participating in negotiations to buy uranium in Khartoum, Al-Fadl said he received $10,000 from al-Qaeda for a job well done. He told the court that he didn’t know whether the deal had been consummated.

Salaries varied, a subject of contention. Al-Fadl, who was born in Sudan in 1963, was paid $500 a month. He said he once went to Bin Laden and complained.

“Some people, they get a little and they want to know if we all [are] al-Qaeda membership; why somebody got more than others . . . . I tell him the people complain about that, and myself too.”

He said Bin Laden replied that some members lived abroad in their home countries and traveled a lot and that he tried to make them happy with higher salaries.

The organizational chart of al-Qaeda was simple. Several committees reported to a Shura Council of leaders.

These included a military committee that conducted training and bought weapons; a money and business committee that ran al-Qaeda’s companies; the fatwa (religious edict) and Islamic study committee; and a media committee that published a weekly newspaper about Islam and jihad (holy war).

Al-Fadl said al-Qaeda had relations with a number of other terrorist organizations, including groups in southern Lebanon, Egypt, Algeria, Libya, Yemen, Syria, the Philippines, Ethiopia and the breakaway Russian republic of Chechnya.

It also maintained bank accounts in England, Malaysia, Sudan, Hong Kong and other parts of the world, as well as guest houses in a number of countries where members stayed.

Al-Qaeda dealt largely in cash, which was used to buy farms and the guest houses as well as to pay travel expenses for missions.

Al-Fadl said he once delivered $100,000 in American hundred dollar bills to a Bin Laden associate in Jordan. He said that he put the money in his bag with his clothes and that the associate arranged for Jordanian customs officials at the airport to not examine the bag.

On another mission, he said he used cash to buy about 50 camels to smuggle weapons to a jihad group in Egypt.

While characterizing Bin Laden as a terror leader willing to order murder and mayhem on a massive scale, Al-Fadl said his former boss did not abide thievery. Al-Qaeda’s chief executive ordered Al-Fadl to repay the $110,000 he embezzled and told him bluntly:

“I can’t forgive you until you give [back] all the money,” Al-Fadl testified.

Prosecutors have charged Bin Laden in the August 1998 bombings. The dead included 12 Americans. He also is a prime suspect in the Oct. 12 bombing of the U.S. destroyer Cole off Yemen that killed 17 sailors.

Bin Laden is believed to be hiding in Afghanistan under the protection of the Taliban regime. The U.S. has offered a $5-million reward for his capture, and CIA Director George J. Tenet said last week that Bin Laden’s network is the most “immediate and serious threat” facing the United States.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.