McVeigh Shows a Defiance Even as His Execution Nears

- Share via

WASHINGTON — When he was sentenced to death four summers ago, armed federal marshals flew him away to prison. They took him by helicopter high up over the Colorado Rockies.

His hands and feet were shackled but his eyes rarely left the window. He could see the mountain streams coursing, the deer and elk running free. He smiled. “Just let me out,” he said. “Give me a head start.”

For Timothy James McVeigh, the race is almost over.

This spring he is scheduled to die for the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The blast killed 168 people and injured more than 500 others. It stands as the worst act of terrorism in the United States.

There are many who wish McVeigh dead--most of his living victims and their families, much of the public, the federal government. Oddly enough, so too do many in the same far-right movement that led the Persian Gulf War veteran to pack a Ryder truck with explosives in hopes of igniting a second American Revolution.

McVeigh has always been the silent, stoic soldier. Now, against the best advice of his attorneys, he has abruptly abandoned his legal appeals and asked for a swift execution.

Barring a last-minute attempt for executive clemency, the Oklahoma City bomber will die on May 16.

Why the sudden change of resolve? Why give in after so much fight? Why would McVeigh, a gun nut from the Buffalo, N.Y., area, surrender to the enemy?

McVeigh has declined so far to fully explain his decision. His lawyers said that he simply doesn’t want to put off the inevitable. “It’s not in his nature just to stall for the sake of delay,” said attorney Rob Nigh.

Others who are close to McVeigh said he relishes being crowned a martyr, that he believes his death finally will spark a national revolt. By dismissing his appeals, they said, he believes he will die on his own terms and not at the hand of the hated federal government.

Many in the anti-Washington crowd reject such a notion, pointing out that the Oklahoma City tragedy actually triggered tougher gun laws and other government restrictions. “He never was a part of the Patriot movement,” scoffed John Trochmann, a high-profile militia leader in Montana.

Some said that McVeigh, having already tasted fame, is merely seeking more celebrity and that, in his own twisted thoughts, dreams that he will live on after death.

In fact, in a letter published today in the Sunday Oklahoman, McVeigh seeks public broadcast of his execution and questions the fairness of limiting the number of witnesses.

A psychologist who studied him at length for the government said that McVeigh’s strong narcissistic tendencies, coupled with years of prison isolation, have brought on a grandiose sense of self. “There’s even a sense of immortality here, that somehow execution or death is not real,” the psychologist said. “Instead of being frightened of death, he embraces it.”

McVeigh is now the first in line on death row at the federal prison in Terre Haute, Ind. His death would mark the first federal execution in nearly 40 years. He will have just turned 33. He will be strapped to a gurney and given a lethal injection.

*

Since April 19, 1995, the day of the Oklahoma City bombing, the world has heard little from McVeigh.

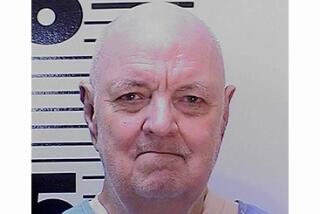

He remains thin and pale, with close-cropped hair.

He still reminisces about his Army days, the one bright spot in his young life. Something as simple as a recent letter from James “Bo” Gritz, once a decorated Army colonel, now deep in the militant antigovernment movement, addressing him as “Sgt. McVeigh” is enough to prompt a quick reply from the man who killed Iraqi soldiers from his post in a Bradley fighting vehicle.

In prison he has been polite and of little trouble. Officials said he “gets along.” When he is moved, he critiques the precision and safety of the guards who escort him up or down the prison hallway.

He knows his notoriety extends far beyond the others on death row. Yet he manages to live alone, calling on the survival tactics he learned a decade ago when preparing--unsuccessfully--for the Army’s Special Forces Unit.

And while McVeigh has been described as a voracious reader of history and other nonfiction books, some said that he prefers pornography. Sometimes he has clipped out magazine photos of young women like Britney Spears and sent them to pen pals, with his own crude inscriptions.

For a while, he received stacks of letters from European women who felt romantically drawn to the troubled inmate. During another period he was mailed enough Gideon Bibles to fill a Holiday Inn.

He can present himself as a great thinker. But in his cell he watches old movies or scans the dial for “The Simpsons” or “Star Trek” reruns. He often would rather talk football than politics or gun control. He tends to be more interested in the Buffalo Bills than the Brady bill, which became a law regulating the sale of hand guns.

He never spoke at his trial, and he rarely surfaces in media interviews (though there are hints that he may reveal some of himself in an upcoming book by two Buffalo journalists). He declined to be interviewed by The Times.

More significant, he has never expressed a drop of remorse. Even at his trial, he never teared up at the stories of lost loved ones, including the 19 children killed in the building’s day-care center.

If he goes quietly, then, he goes without explanation.

“It is a combination of his narcissism and boredom,” said the government psychologist, who asked not to be identified.

“If you could get inside his mind, there would be a lot of grandiose fantasies,” the expert said. “He was a sensation-seeker. To the max.

“And being in prison, particularly in general isolation, is just exceedingly boring. Particularly if you’re drawn to sensation. I mean high levels of risk-taking, for people who relish hang-gliding or jumping out of planes. He would be deeply bored and feel it consciously day in and day out--to where there’s a desire to not have to face it endlessly any more.

“So the risk of eternity is much more stimulating than the boredom of maximum security for the next 40 years.”

*

During the trial, McVeigh was the center of his own universe. His prison handler was Larry Homenick, then-chief U.S. deputy marshal in Colorado. At that time, McVeigh was kept at the U.S. prison in Inglewood, Colo., and in a special lockup below the federal building and courthouse in Denver.

“The very first time I saw Timothy McVeigh, he was housed in a wing of cells and had the whole wing to himself,” Homenick recalled. “He was bouncing a handball against the wall. It reminded me of that movie, ‘The Great Escape,’ with Steve McQueen, where he is bouncing a ball into his mitt.”

McVeigh had a sheepish grin. “You won’t have any problems from me,” he told Homenick.

The two got along well, their rapport bolstered by Homenick’s service on a river patrol boat in Vietnam. The basement lockup consisted of several rooms, and McVeigh had the run of the place.

There was a refrigerator for soft drinks. He was well stocked with cookies and fruit and his favorite: burrito supremes from Taco Bell. He rigged up an antenna on his radio to search for Buffalo Bills’ games.

He even broke up Styrofoam coffee cups and slipped the pieces underneath the bed legs so the new floor would not be scuffed.

“Here’s a guy who blew up a federal building and he’s concerned about the floors,” said Homenick. “And he would get up every morning and fold his bedding. And fold all his clothes, and put it in a nice, neat pile in the corner.”

A small exercise yard was built on top of the high-rise federal building. It afforded fresh air and a panoramic view of the sky. But when McVeigh asked to be brought up, he turned his gaze down at a billboard with the image of a local TV anchorwoman. “He liked to look at her picture,” Homenick recalled.

He was flooded with Bibles and letters. “He was quite surprised that so many people would write to him. And he described many of them as crackpots. He looked at himself as normal, and them as crackpots.”

Only once did Homenick see McVeigh flare up. That was moments after he was formally sentenced to death and the marshals ordered him to remove his shoelaces--for security reasons.

McVeigh cursed. He was still the same Tim McVeigh, he argued. The guards acquiesced and he got to keep the laces. Then came the grin again. “I guess it’s been shown the government doesn’t always win,” he said.

When it came time for the helicopter ride out of Denver, McVeigh had a parting salute for Homenick. He gave it in military jargon. “Thanks for the tour,” he said.

*

He was flown to Supermax in Florence, Colo., the federal government’s most secure prison, because federal death row had not yet opened. So there in central Colorado, McVeigh was housed with other notorious convicts, like Unabomber Theodore J. Kaczynski and World Trade Center bomber Ramzi Ahmed Yousef.

Yousef’s attorney, Bernie Kleinman, recalled stories his client would tell about McVeigh, whom he met when they were taken outside to their exercise cages.

“It was a cage with a steel-wire mesh,” Kleinman said. “The exercise consists of walking in circles. You can look up and see the sky. If you look at an angle, you can see a sliver of the Rockies.

“But they could talk through the mesh.”

Mostly they talked about the classic movie shown on the prison TV the night before. “Or they talked about women,” Kleinman said. “Every man in prison talks about women.”

Later McVeigh began corresponding with Kleinman, even sending him pictures of women.

Yousef never believed that McVeigh could have destroyed the federal building by himself and killed so many people. Six people died in Yousef’s crime, the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

“He felt that Tim was an idiot,” one prison source said. “That he could not have constructed such a complex bomb. It was his opinion that McVeigh never had the capability of doing that.”

Yousef did not think McVeigh was innocent, just that he could not have acted by himself. What sealed Yousef’s belief was that McVeigh seldom discussed politics. One source said that McVeigh rarely read the papers, instead subscribing to magazines with racy photos. “He was a good source for porn in the prison.”

*

In 1999, McVeigh was moved to the new Special Confinement Unit/Execution Facility at the U.S. Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Ind. This is federal death row.

Soon he wrote The Times to complain about prison treatment of Cuban inmates from the Mariel boat lift. “Got these Cubans across the hall I’m able to talk to but not see,” he wrote. “Discussions are hampered by loud fans.”

He described his new surroundings. “I’ve been making adjustments to the new pad,” he said. And of course he brought up the Bills and quarterback Doug Flutie. “Okay, gotta run,” he said. “Go Flutie!”

But there was little to be cheery about.

His cell is 8 feet by 10 feet, and 12 feet high. He is allowed three showers a week, and about five hours a week of “rec time.” Otherwise, said prison spokesman Dan Dunne, “it is total lock-down.”

He can have a deck of cards and a crossword puzzle; a book from the prison library maybe. “But no pornography,” Dunne said. “No Playboy.”

Fellow death row inmate David Paul Hammer wrote The Times that “the thing Tim prides most is his reputation and all that entails.”

“You should have heard how he reacted to broadcast reports about CRIMES OF THE CENTURY and the fact that he wasn’t at the top of the list, being beat out by the Kennedy Assination [sic],” Hammer wrote. “That the O.J. Simson [sic] case was number four also set him off on a tirade.”

Hammer added:

“Did you know that Tim is still a virgin. . . ? This has caused him to have much confusion and to fear that exposure will destroy his image, which he believes is his only real asset.”

*

McVeigh spoke by satellite hookup in December when he asked U.S. District Judge Richard P. Matsch in Denver to schedule an early execution date. The decision was his alone. “I am under no duress from the conditions of my confinement,” he said.

He added that he was drug-free, except for taking “Zantac or Pepcid, that kind of thing,” for heartburn.

The judge set the execution for May 16. But he gave McVeigh one out. He still could file for executive clemency but he must do so by Friday, Feb. 16.

That is clearly a longshot. President Bush, a strong proponent of capital punishment, was governor of Texas when 152 inmates were executed. In a note to the Buffalo News last month, McVeigh acknowledged as much. “I harbor no illusions that George ‘The Reaper’ Bush would grant me a commutation of sentence, nor would I beg any man to spare my life.”

His appellate lawyers are urging McVeigh to seek clemency, if only to buy more time, maybe another month or so.

But Randy Coyne, a lawyer who helped represent McVeigh at trial, said that his former client is a realist.

“He didn’t become a sergeant in the Army by being some chowderhead,” Coyne said. “He accepted the death sentence. Stoicly. Bravely.

“Just like that scene in the movie ‘Full Metal Jacket’ where the sniper is taking apart a guy and the commanding officer says it’s a [lousy] situation but you just have to learn to accept it.”

*

Many of McVeigh’s old friends cannot understand why he wants to die.

“He was a young man growing up here, a child in fact,” said Lynn Drzyzga, a neighbor who knew him as a boy in Buffalo. “I can remember him digging my car out of the blizzard of ’77. I put yellow ribbons around our tree when he was in the Gulf.

“But now, how much he has changed.”

Another neighbor, Elizabeth McDermott, was stunned when he dropped his legal appeals. “I thought he was more optimistic than that.”

James Nichols, a Decker, Mich., farmer, is the brother of Terry L. Nichols, who is serving life with no parole for conspiring in the bombing. He believes the government turned both men into “patsies.”

He does not want McVeigh to go without first clearing his brother. And he is sure the government drugged McVeigh, or influenced him somehow, to make him want to die.

“They’ve got him brainwashed into thinking he done it,” Nichols said. “Only thing is, he doesn’t know it. He’s locked away.”

Bob Papovich, a Cass City, Mich., sign painter and fellow government malcontent, said that McVeigh often writes him and that they visited once in prison.

Now McVeigh has sent him written instructions, he said. He wants to be cremated and is resisting a government autopsy. Papovich and an Army buddy are to “escort” his ashes to New York.

He said McVeigh remains cheerful and even has joked about death.

“I don’t think he’s afraid to die,” said Papovich. “He’s been a soldier. He’s faced that before.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.