The No-Funds League

- Share via

CANTON, Ohio — They glide through the spotlight on a cloud of euphoria. Howie Long, Joe Montana, Ronnie Lott, Dave Wilcox and Dan Rooney have come to this small Ohio town for a dream weekend, to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Along with them have come 103 others previously inducted, invited for the grandest reunion in football history.

But it hasn’t been so grand for many of the former players in the years since they moved out of the spotlight.

Some limped into Canton. Jim Otto, former Oakland Raider center, has had 30 operations on his battered body. Willie Wood, former Green Bay Packer defensive back, has had both knees rebuilt.

Others limped in under the weight of financial burdens, hiding the embarrassment of having to depend on others to bail them out.

A few might not have been here at all if not for Cloyce Box.

Who?

Few players remember him. Most fans have long forgotten him. But aid, not adulation, was Box’s concern.

The former Detroit Lion end and halfback started and perpetuated a secret fund to help former players who could not help themselves, a fund that has outlived him but remains largely unknown to this day.

Many former players aided by Box felt as if they had been touched by an angel, an angel who sprouted wings back in the days when the NFL looked the other way when a needy old-timer limped by.

In 1962, the league instituted the Bert Bell retirement plan, which provided a pension fund, disability money and emergency resources for all those who had played in the league from 1959 on.

In a league that began in 1920, many desperate cases were excluded.

The league brought the older players into the plan in the late 1980s with an additional outlay of $10 million. Now, all are included in the collective bargaining agreement.

But until then, the old-timers who ran out of money or out of medical care would have been out of luck.

Except for Box.

You would have to be a student of the game, a die-hard Detroit Lion fan, or an impressionable young fan who knew all of the players in that era, just to know who he was. But the old players know. Some will never forget him.

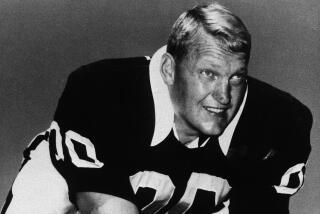

Box passed through the NFL without much notice. Drafted out of West Texas A&M; by the Washington Redskins in 1948, Box was traded to the Lions, where he played from 1949-54.

And then Box retired, moving on to the oil-gas business, in which he became highly successful.

In 1982, he put together a reunion of the NFL champion Lions of 1952 at his Texas home. Box had decided that his old teammates, who had received nothing more than jackets to commemorate their triumph, deserved more. So he had championship rings made up for each member of the team.

While visiting with many of his former teammates, Box began to realize just how miserable some of their lives had become.

Keep in mind, these were players who made about $5,000 a season, with the big stars earning perhaps $10,000, or maybe $20,000 for a superstar.

Lou Creekmur, a former Lion offensive lineman on hand in Canton this weekend, had to work at a shipping company during the season just to survive financially.

“I would play a game on Sunday and then be at work Monday morning,” Creekmur said. “I’d work from 7 a.m. to 9:30 on weekdays, go to practice, and then come back to work at 2:30 in the afternoon.

“I thought nothing of it. I didn’t know any better.”

Road trips didn’t even provide relief from the everyday working world for Creekmur.

“If we went to, say, San Francisco for a game, my company expected me to keep working,” Creekmur said. “I’d have to go knocking on the doors of clients in that city on Friday and Saturday.”

At that, Creekmur was one of the lucky ones. He had an alternate job.

Said Hall of Fame receiver Dante Lavelli of the Cleveland Browns, “When you got cut in those days, there was no players’ association to protect you. You were out in the cold world.”

When Box learned how many former players were marooned in that world, he started his secret fund. Although several high-profile players of the time--Frank Gifford, Bobby Layne and Doak Walker--served on the board of directors and helped identify deserving recipients of the Box fund, it remained a well-kept secret.

“I didn’t know about the fund,” said Hall of Famer Yale Lary, who played with Box. “But I know that he was a man who would never forget his buddies.”

Not one Hall of Famer questioned about the fund this weekend admitted to knowing of its existence.

Yet exist it still does, even though Box died in 1993 and the league has long since assumed responsibility for picking the recipients.

The fund is still run out of Texas by Tom Box, one of Cloyce’s sons. More than $300,00 has been paid out to players, coaches, an official and anyone else connected with the game who has been deemed worthy.

“We have also provided wheelchairs, other medical equipment, and in-house medical care,” Tom Box said. “It all depends on what someone needs. In one instance, a former player wrote us saying he needed tires for his car. We got him tires.”

The fund was kept secret to avoid the possible humiliation of those served by it. So Tom wasn’t about to reveal the names of players helped.

But he certainly wasn’t hesitant to talk about his father’s resolve.

“It was hard for him to accept the conditions he found for some of the players,” Tom said. “They didn’t have pensions or benefits. To think of their lives in tattered old houses or in lonely places out in the country was just horrible. There were a lot of players living literally in poverty, a lot of pros having fallen on tough times. When my father heard some of the stories, he just felt something needed to be done.”

Box was continuing a tradition begun by Layne, the late quarterback known as much for his generosity as his talent and carousing.

Creekmur smiled while recalling the phone calls he would get from Layne in their playing days.

The conversation, according to Creekmur:

Layne: “So-and-so is having some money problems. I need a hundred bucks from you and everybody else on this team.”

Creekmur: “I just don’t have it, Bobby.”

Layne: “Damn it, I want a hundred bucks.”

Pause.

Creekmur: “OK, Bobby, you got it.”

Box didn’t ask anybody else to chip in. He was happy, and able, to do it himself.

In his five years in the league, Box finished with 82 yards rushing, 2,665 yards receiving and 32 touchdowns.

Hardly numbers worthy of the Hall of Fame.

But if it were up to the players of his era, Cloyce Box would have long ago had an honored place in Canton.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Hall Of Fame

Class of 2000

HOWIE LONG

Defensive Lineman

Oakland-L.A. Raiders, 1981-1993

RONNIE LOTT

Defensive Back

San Francisco 49ers, 1981-90;

L.A. Raiders, 1991-92;

New York Jets, 1993-94

JOE MONTANA

Quarterback

San Francisco 49ers, 1979-92

Kansas City Chiefs, 1993-94

DAN ROONEY

Team President

Pittsburgh Steelers

DAVE WILCOX

Linebacker

San Francisco 49ers, 1964-74

* Induction ceremony: Today, ESPN2, 8:30 a.m. PDT

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.