Creating Contraptions Is Not Mystery Science to Him

- Share via

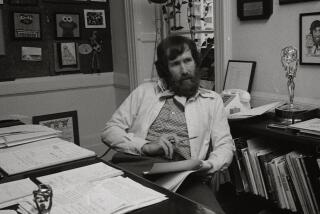

Joel Hodgson was flying high. In fact, he was in orbit.

As Joel Robinson, the sleepy-eyed, genially mopey janitor forced to sit through and heckle crummy movies on the award-winning cult TV hit “Mystery Science Theater 3000,” Hodgson had critical acclaim and a loyal fan base.

Sure, he was on cable, Monopoly money compared to network megabucks, but as creator and executive producer of his Minneapolis-based series, he had more creative freedom than most TV artists.

And yet, in 1995, Hodgson jettisoned himself from “MST3K,” the moniker by which the show’s fans know it, in its fifth season, bailing after mercilessly slagging Joe Don Baker’s performance as a boozy cop in a queasiness-inducing flick called “Mitchell.” Except for brief appearances on such things as “The TV Wheel,” a special Hodgson created for HBO, Hodgson has flown beneath the radar since then.

And that’s the way he prefers it. With his brother Jim, a sculptor who has been a consultant for New York art museums, Hodgson has started Visual Story Tools, a company that creates Rube Goldberg-style magic for the Digital Age. In their Sun Valley warehouse-cum-laboratory, the two tinker on quirky contraptions that amuse them and allow others to rethink the way they look at television.

They’ve created, among other things, a miniature carnival ride for the new live-action opening sequence for the Cartoon Network’s quixotic cult fave, “Space Ghost Coast to Coast,” and have consulted for effects on the FX series “Penn & Teller’s Sin City Spectacular.” They’re developing a handful of series for the upcoming cable channel named for the late Jim Henson.

That hasn’t prevented some fans--including some who have left withering postings on Hodgson’s Web site--from feeling that the former prop comic and magician (he recently appeared at the Magic Castle) has squandered his career. Hodgson, however, insists he’s perfectly happy remaining behind the camera.

“Performing on [“MST3K”] was kind of a necessity because I was the most well-known guy,” Hodgson said in his Sun Valley work space. “I had done ‘Letterman’ and ‘Saturday Night Live.’ So it was kind of a promotional thing, kind of like Chuck Barris. I read where he hated doing ‘The Gong Show,’ but it worked for him.”

‘He Loves the Creative Process’

Hodgson collaborated with his friend Nell Scovell on the direct-to-video hit “Honey, We Shrunk Ourselves,” and they were script doctors on “George of the Jungle” (they convinced wary Disney executives to let the apes speak). The brothers created tricks and special effects for the first season of “Sabrina, the Teenage Witch,” an ABC series that Scovell co-created.

“Joel’s so inventive,” Scovell said. “He approaches his projects with so much love. He loves the creative process; he’s not about making money. He’s about creating something new, not just something successful. He’s so pure in a town without a lot of purity.”

Yet for all the fun and clever gizmos they create, the brothers Hodgson address their creations in serious, strictly business fashion. They discuss their work in arid, practically academic fashion--Jim Hodgson uses phrases like “peer groups” without any irony; his brother dryly intones such bons mots as “Jim and I are real students of creativity.”

The Hodgsons differ from most writers pitching ideas in that rather than type up scripts, they first build model sets to see if their ideas will fly.

Many of the Hodgsons’ ideas employ puppetry, including “MST3K.” “We really try to develop things from the ground up,” Joel Hodgson said. “Most people involved in making shows tend to be involved with the story. And we’re different because we get involved with all the various aspects, try to consider where you would hide all the puppeteers and then write the script. It creates a bottleneck if you create something that looks great on paper but can’t be shot. You can pitch really beautiful ideas, but there’s a stark reality as to what comes out.

“Most people in our position just have a word processor,” he said. “We feel that should be the second step. That’s why we over-deliver [by building miniature sets]. I hate nothing more than that term-paper mentality, where ‘We have to save the show!’ because you didn’t anticipate the puppet couldn’t do something you scripted and you stay up all night rewriting.”

Remaining Artistic Despite Politics

The brothers were inspired by their father, who built Rube Goldberg-style objects in his spare time. Jim Hodgson’s art background has proved a boon for the duo’s creations, and he doesn’t seem to have had trouble adapting to Hollywood’s often less artful mentality.

“There is more dough here, and the opportunities are much broader, I’m realizing,” he said. Asked to compare Hollywood’s cutthroat politics with those in the art world, he said simply, “It doesn’t seem any different.”

Politics was one of the reasons Joel Hodgson split from the other writers on “Mystery Science Theater 3000.” The show was infinitely influential in this era of information overload--not only did it present a movie, it also commented on every aspect of it. “Beavis and Butt-head,” “Pop-Up Video” and “Talk Soup” have all taken the same basic concept.

On the show, Joel Hodgson’s silhouette sat in the bottom left corner of the frame as he hurled mile-a-minute potshots at junk classics (“Robot Monster,” “The Wild World of Batwoman”) with puppets he built the night before the show’s first taping at a local Minneapolis TV station.

The show began in 1987, when Jim Mallon, who was working at KTMA in Minneapolis, approached Joel Hodgson about doing a local stand-up comedy show, the likes of which were inundating cable. Hodgson countered by suggesting his idea and, with Mallon and Kevin Murphy, who also worked at the station, brought a new dimension to film criticism.

“They were like the guys in high school who had the keys to the AV room,” Joel Hodgson recalled. The show was an instant hit, and they subsequently sold the idea to the Comedy Channel (now Comedy Central). Within two seasons, it was the cable station’s first media sensation.

Rumors suggest that Hodgson’s split from his “MST3K” colleagues was fairly acrimonious. In “The Mystery Science Theater 3000 Amazing Colossal Episode Guide,” written by the show’s remaining performers and writers, Hodgson’s departure is glossed over, except for a mildly snide response to his quote in a press release announcing his departure that refers to “creative ecology”: “It seemed an oddly stilted thing to say.”

Hodgson’s circumspection about his departure nonetheless hints that he may have been difficult to work with.

“As the show started to grow and got more famous, everybody’s image of what it was supposed to be got kind of cloudy,” he said. “I was pretty young, I didn’t have any experience, I had always worked alone as a stand-up. So I didn’t have any experience or inner-office skills. We had 18 people and were producing 24 shows a year. And I was trying to maintain the creative aspect and was being pulled into these board of directors meetings.

“I didn’t feel like I was built for that, so I wanted to get back to staying creative. That’s the part where I felt I wasn’t built for holding on, trying to maintain that seemed too hard. It wasn’t creative, ultimately.

“It was very frustrating for me,” he added. “ ‘MST’ worked for me on so many levels--creatively, commercially it worked great--and it was frustrating because I was having a power struggle with my partner [Mallon], who wanted creative control. Creativity doesn’t exist in a power struggle. I felt OK about walking away from it. My experience from doing stand-up is that you can’t keep telling the same joke. People get tired of it. And you don’t want to be caught holding the bag when it ceases to be funny.”

Head writer Mike Nelson took Hodgson’s position, and the show maintained its popularity for a couple of seasons. Eventually, however, Comedy Central allowed the show to move to the lower-profile Sci-Fi Channel.

Whatever enmity existed between the two parties seems to have abated, however. Hodgson will do a cameo appearance on the season opener for this, its 10th year on the air.

Getting the Visuals Before the Script

Meanwhile, the Hodgson brothers are looking for the next pop-culture sensation, and they believe that Visual Story Tools and the expanding computer universe will help them find it.

“We feel that’s where the trend is going, starting with the visual rather than the written,” Joel Hodgson said. “Little kids watch TV before they can read. We’re not just writers, we’re designers. That’s what makes us unique, and it’s also a little troublesome because Hollywood is geared toward scripts. If it doesn’t fit on a piece of paper, it can’t flow through the system. But that’ll change when anybody can, in the comfort of their own office, burn stuff onto a CD-ROM.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.