Great Expectations : Like the opening that can make or break a Hollywood film, initial album sales are increasingly being viewed as important. Insiders lament the trend’s long-term effects on recordings and artists.

- Share via

Bold predictions about blockbuster opening-week grosses typically come out of Hollywood, not Nashville, so it’s understandable that more than a few music industry eyebrows are being raised over the boast from Garth Brooks’ label that his new album could sell a staggering 1 million copies the first day it hits stores, Nov. 17.

The prediction that “Garth Brooks Double Live” could blow away all first-week sales records in a mere 24 hours not only defies industry convention--most labels are loathe to forecast or even discuss early sales--it also promotes the perception that, like films, major new albums live or die by their opening performance.

And that, insiders say, is unhealthy and shortsighted for a business that has long coveted albums with “legs”--the ones that sell strong over months, not days.

“I think people get caught up in the hype, and misuse the data,” said Mike Shalett, chief operating officer of SoundScan, the industry service that tracks and reports album sales. “People treat it like it’s movie box office, but it’s different. . . . It’s about longevity.”

Somehow, Shalett says, the focus has shifted away from chart stamina to big sales splashes. “Now Garth Brooks could sell 750,000 copies--at a gross of something like $8 million--and people would be unhappy,” he said. “I don’t get it.”

Observers say Capitol Nashville is hoping to stimulate sales by encouraging the country star’s loyal fans to buy the record immediately and help him add to his list of commercial pop milestones.

Brooks has sold more albums in the U.S. than any other solo artist in history--well over 60 million. And now, his label expects him not only to beat the first-week sales mark for a two-disc CD--the Beatles’ “Anthology Vol. 1” sold 855,473 copies--but also to overtake the single-disc debut total set by Pearl Jam’s “Vs.,” which sold 950,378 units.

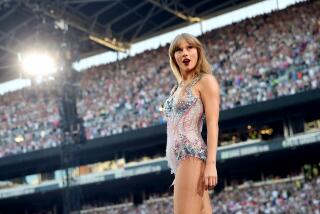

The country star’s new release is being accompanied by the fanfare usually associated with an “event” movie. On the evening of the album’s release, Brooks will perform a closed-circuit concert to be shown exclusively in 2,300 Wal-Mart stores. The following evening, he’ll perform three live one-hour concerts--one for each time zone--on NBC.

That sort of hype might be hard for most acts to live up to, but Brooks’ amazing success has put him in a category by himself.

For the industry at large, however, the tendency to hype and dissect first-week sales may harm the chances of an album that too quickly gets branded as a disappointment in a business that is driven largely by perception. Indeed, a survey of label executives, radio programmers and others in the music industry suggests that an album tagged early on as a disappointment may lose airplay, media exposure and even some fan support.

Waiting for Wednesday

That tendency is in part driven by the speed and relative precision of sales information in the era of SoundScan, which began tracking album sales in 1991. In a bottom-line business, winners and losers are declared every Wednesday morning when the previous week’s sales totals hit fax machines from Los Angeles to New York and Nashville.

“People in the music business go to work earlier on Wednesday than any other day,” says Geoff Mayfield, director of charts for Billboard, the industry journal. “Some get up before the crack of dawn to dial it up on their computers. They want to see how their stuff is selling.”

The problem, many say, is when early performance is viewed as a final grade.

“People are watching the first-week sales too closely because, of course, it doesn’t tell the whole story,” says Bob Bell, a new-music buyer for the Wherehouse chain. “There’s lots of cases where the expectation is too great. An album with a nice long run can still be perceived as a disappointment because the first week wasn’t what was expected.”

Lackluster first-week sales for a major new release will not “make or break” the album, most agree, but it is a factor in playlist decisions according to radio programmers such as Tom Poleman with Z100 in New York.

“We have a lot of interest in the number of units being sold,” said Poleman. “We go with our gut first and foremost, but [SoundScan] puts you in touch with how people on the street are reacting.”

And in cases where gut reaction is contradicted by early performance at the cash register? “If something is not doing as well as we expect, we might back off, yes,” Poleman said. On the flip side, surprisingly strong sales can win more airplay, he said.

The attention devoted to debut sales by the industry and the media is difficult to escape, even for industry insiders who resist getting caught up in the numbers game.

“First-week sales don’t mean anything to us over here,” says Peter Mensch, co-manager of such artists as Madonna, Metallica, Smashing Pumpkins and Hole. “It’s one of the stupidest things you can do, saying the first week makes or breaks an album. At our meetings I say, ‘The first person who brings up first-week sales can just get up and leave.’ ”

Speculating in Private

Most record executives, of course, privately calculate what they expect to sell the first week and beyond, but most refuse to broach the subject publicly.

First-week sales for Alanis Morissette’s hotly anticipated “Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie” will be released Wednesday, but her camp has steadfastly refused to make predictions. The thinking: With so much scrutiny already directed at the follow-up to “Jagged Little Pill,” the 1995 album that has sold more than 15 million copies in the U.S., why fuel expectations even higher?

“The strength of the Morissette album, the success or failure of it, will be judged long after the first week has come and gone,” Mensch said.

Morissette’s breakthrough album, released when she was 21, transformed her from a light pop singer in her native Canada into a phenomenal commercial and critical success. With that standard set, her managers and label are eager to focus attention on the new album’s music, not its money-making potential. Regardless, like other artists coming off huge debuts, she finds herself facing perhaps unreasonable expectations.

Several record executives and retailers cited the second Sheryl Crow album on A&M; Records as a prime example of an album unfairly dismissed as a disappointment because of mild first-week sales of 72,000. That album, 1996’s “Sheryl Crow,” eventually sold more than 2.2 million copies after months of steady chart performance. “Thirty weeks of strong sales and [Crow] was still hounded by questions about why the album wasn’t doing well,” one publicist said. “Ridiculous.”

Bellwether of Success

Still, an argument can be made that for new albums from established superstars--such as the releases this month from Brooks, Morissette, Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, Jewel and others--the first week can be a bellwether of its eventual success. A bad debut-week showing does not certify failure, but a huge first week for established bands often means big sales ahead.

In the case of Pearl Jam, for instance, its 1993 album “Vs.” set the standard for first-week sales in the SoundScan era and went on to sell more than 6 million copies. Its 1996 release, “No Code,” however, sold an initial 367,000 units and has sold about 1.4 million copies to date.

To Pat Quigley, president of Capitol’s Nashville division, first-week sales reveal the number of people who will buy a new album right away based “on their love” for the star. Estimating that Brooks has 5 million core fans, Quigley was unafraid earlier this month to predict the country music king’s new release could hit unprecedented numbers.

Last November, Brooks had the strongest first-week sales of any 1997 album when “Sevens” sold 897,000 copies. If the new double-album ends up merely matching that total for the week, he may find himself, like Crow, answering questions about disappointing sales.

Danny Goldberg, chairman and president of Mercury Records Group, said charts and rankings, along with the emphasis on immediate success, are a product of media fascination and analysis of the entertainment industry.

“The [first week] sales numbers matter, of course, but I don’t think it’s a big deal to people in the business,” said Goldberg, whose label handles Shania Twain and Hanson. “It’s fun being No. 1 even for a minute, but would I rather have an album debut at No. 1 and then drop right out of the chart or one that does better over the long run?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.