Hard-Won Political Access May Soon Be Lost or Stolen : Civil rights: Let’s honor the 30th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act by voting.

- Share via

People attempting to register to vote should not be beaten with billy clubs by police because of their skin color. Yet this is what the nation saw happening in Selma as they watched their TVs on Sunday, March 7, 1965.

The resulting national outrage over the now-infamous “Bloody Sunday” prompted Congress and President Johnson to enact the Voting Rights Act, which outlawed many barriers aimed at preventing African Americans in the South from registering to vote and exercising their full political rights.

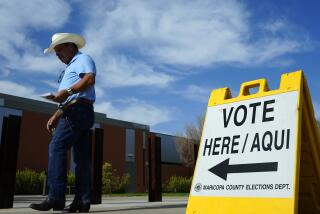

But as we mark the 30th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act this month, it should properly be celebrated by all Americans, not just African Americans in the South. It was a watershed law that actively sought to end discrimination and give all citizens equal opportunity to participate in the political process.

That law’s long arm touches all of us today. The bilingual ballot provision of the Voting Rights Act requires that in parts of Los Angeles County, ballots are available in languages such as Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog and Korean. Other provisions ensure that discriminatory tactics and political trickery do not flourish in the Golden State.

The law signed 30 years ago brought down barriers such as poll taxes, literacy tests (they often included questions about obscure sections of state constitutions), complicated registration forms and intimidation tactics. Citizens were afforded redress and federal protection at polling places. The government’s action was long overdue--nearly a century of struggle had elapsed from 1870, the year former slaves were given the right to vote by the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The Voting Rights Act has had a positive, direct impact on African American political participation, increased registration and the election of African Americans to public office. This has occurred despite three amendments, less than enthusiastic U.S. presidents and sporadic Department of Justice enforcement. The fact remains that before the act’s passage there were only 300 black elected officials in the entire nation; by 1993, the number had climbed dramatically to around 8,000.

Despite such progress, divisive forces are at work today to dismantle civil rights and voting rights programs. Right-wing political organizers seek to eliminate affirmative action through the courts. Also, in a rollback of the Voting Rights Act, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled this year in Miller vs. Johnson that it is unconstitutional to redraw the boundaries of political districts to maximize the election prospects of historically disadvantaged groups. The court ruled that the federal government can intervene only to prevent discrimination in proposed redistricting plans. The belief behind such moves is that government involvement is ruining the republic, particularly in the area of race relations. Everything is fine with such advocates as long as not too much benefit is afforded women or minorities, which is incorrectly assumed to be at the expense of white men.

But less civil rights protection will have serious, negative social effects. The Miller decision, for example, is likely to unseat a significant number of Latino and African American officeholders at all levels of government. It took 30 years to elect the current 41 black members of Congress. The prospect that the Miller decision could wipe out more than one-third of the African Americans in Congress is a matter of grave concern.

We cannot afford to turn the clock back on 30 years of progress. A denial of rights is wrong whether or not discriminatory intent can be proved. Government must actively try to integrate all areas of society. Racism is a pervasive virus that is difficult to kill. Given the current deficit after years of discriminatory restrictions, a century or more will pass before we have a nation that reflects its diverse population in all of its institutions unless government steps in.

The 30th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act can best be celebrated by viewing it as a successful example of government intervention on behalf of all groups discriminated against.

But the beneficiaries should take nothing for granted: They must register and vote in unprecedented numbers to protect their interests which are being viciously eroded.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.