U.S. Probes Early Halt to Arms Sale Investigation : Inquiry: Customs agent in O.C. says he was ordered off case involving $70 million in weapons left in Vietnam.

- Share via

COSTA MESA — The Treasury Department has quietly reopened an investigation into whether U.S. Customs Service officials were pressured five years ago into ending an undercover operation to break up a plot to sell $70 million in arms abandoned in Vietnam, officials said.

Sources in Washington said the new probe was launched because officials believe an initial inquiry in 1993 into the abrupt end of the weapons investigation, code-named Operation Leatherneck, was not complete.

According to documents obtained by The Times and interviews with Treasury and Customs officials, the investigation into two weapons dealers was sanctioned at the highest levels of the U.S. government, including the National Security Council in May, 1990, at a time when federal law prohibited any trade with Vietnam.

Documents show that at least two Vietnamese generals and an official from the Ministry of Tourism were helping the U.S. arms merchants obtain the weapons. The Vietnam trade embargo was lifted in 1994, but it is still illegal for U.S. citizens to purchase weapons left in Vietnam.

The U.S. arms dealers, one, a resident of Miami and the other living in Bangkok, Thailand, had promised to deliver to undercover agents a variety of weapons ranging from F-5 jet fighters to thousands of M-16 rifles, documents said. The weapons, identified in a lengthy inventory list, were supposed to be sold to governments in Latin America or Africa.

The new probe looking into why the undercover operation was terminated began after Customs Special Agent Frank Caliendo, who was suddenly removed as lead investigator in the case and reassigned to an office in Orange County, sued the Treasury Department challenging the decision to end Operation Leatherneck and his removal from the case.

Caliendo, 44, declined to be interviewed, but he charges in the suit that Customs officials retaliated against him for demanding to know why he was removed from the case without explanation. A hearing on the lawsuit is scheduled Tuesday in a Washington federal court.

Treasury Department spokesman Howard Schloss in Washington confirmed that “the Leatherneck investigation has been reopened internally by the [Treasury] inspector general.” The U.S. Customs Service is part of the Treasury Department.

Schloss added that the investigation centers on the role of Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Control, which worked on Operation Leatherneck with the Customs field office in Cleveland.

Sources said that part of the internal investigation will focus on R. Richard Newcomb, director of the Office of Foreign Asset Control.

Newcomb declined to comment, but this is not the first time that his actions in a Vietnam embargo investigation have come under scrutiny. In 1991, he ordered a halt to another Customs investigation of allegations that U.S. companies were illegally doing business with Vietnam. Sources said that the inspector general’s investigation also is looking at the 1991 case.

In a written statement to Treasury Department investigators, Steve Plitman, Newcomb’s former deputy, charged that Newcomb had ordered him to lie to Rep. John Boehner (R-Ohio) about why Operation Leatherneck was terminated. Boehner was making inquiries on behalf of Caliendo and an informant in the case, Mickey Downie, who was a licensed firearms dealer at the time.

“I absolutely refused and told Newcomb that the Leatherneck case had never been fully investigated to fruition,” said Plitman in a three-page declaration, which was obtained by The Times.

Plitman, who was transferred to Customs last month when his job at Treasury Department was eliminated, declined to be interviewed. However, a Treasury Department source said the internal investigation was reopened “in part because of the hell that Plitman raised about Newcomb’s role in Leatherneck.”

Documents show that the initial approval for Operation Leatherneck, which began in Cleveland, was given by the Undercover Review Committee at Customs’ Washington headquarters.

The investigation fizzled when Caliendo, a former Marine officer, was removed and replaced by a younger agent who had no undercover training or experience.

Documents show that the operation was put on hold for two weeks while Caliendo’s replacement took a crash course in undercover work and weapons familiarization.

Richard Siegel, head of Customs Cleveland enforcement office, who ordered Caliendo removed from Operation Leatherneck and later recommended his transfer to California, declined to comment on the new investigation, as did Customs Washington spokesman Steve Duschesne.

The inspector general’s investigation of Operation Leatherneck comes in the wake of an unprecedented agreement reached last month by Treasury Department and Justice Department officials giving the FBI sole authority to investigate allegations of corruption in Customs’ San Diego and Los Angeles districts. Normally, those investigations are done by Customs internal affairs officers and the agents of the inspector general’s office.

C. Russell Twist, who represents Downie in a $20-million suit against the Treasury Department, said that Customs and Treasury officials have repeatedly resisted efforts by Caliendo and Downie to obtain internal Customs reports concerning Operation Leatherneck and Treasury Department reports of the first inspector general’s probe.

Downie, 45, a career informant, charged that misconduct by Treasury and Customs officials in closing the arms investigation cost him $20 million in payments he would have received had the case been prosecuted.

Immediately after leaving Operation Leatherneck, Downie went to work for the FBI as an informant in a corruption investigation of the Cleveland Police Department that resulted in 43 convictions.

Documents obtained by The Times show a web of contradictory reports from Customs and Treasury officials about why the arms investigation stalled.

Initially, the two U.S. arms merchants asked for permission in June, 1989, from the State Department and Newcomb to legally purchase and import the weapons from Vietnam. In a June 12, 1989, letter to Newcomb, one of the partners offered to donate “20% of the profits from the sale . . . to selected nonprofit organizations” in the United States.

Both Newcomb and State Department officials denied permission for the weapons transaction. Later that year, an associate of the two men approached Downie at an Ohio gun show with the deal to market $70 million in weapons stored in Vietnam, not knowing of Downie’s ties to federal law enforcement agencies.

Downie then contacted Caliendo who obtained permission from his superiors to begin an investigation of Downie’s claims. Over the next few weeks, Downie talked several times with the arms brokers and set up meetings to discuss the arms deal, according to the lawsuits filed by Caliendo and Downie.

As the investigation progressed, officials in Washington were informed, and according to one memo from Plitman, Operation Leatherneck “had great support from the White House and National Security Council.”

Four weeks into the undercover operation, Caliendo was yanked from the case without explanation, and Downie refused to work with the new agent assigned to the case. Caliendo and Downie had worked together on a variety of cases for 16 years.

After Customs officials closed Operation Leatherneck, Siegel and other Customs officials claimed that the two arms merchants never intended to go through with the weapons deal. One Customs report labeled the American in Bangkok as “a known con man.”

However, this was refuted by a Treasury Department official who monitored the investigation closely.

“These people weren’t pretending. They were talking price, quantities and dates. We knew they had five ships available to transport all this stuff. We intended to seize the ships too. Caliendo had all this information confirmed, that’s why we made this a Class I [the highest level of undercover operation],” said the official, who requested anonymity.

Documents show that Siegel offered different explanations why his office closed the operation without making any arrests or seizures.

First, he said that federal prosecutors in Cleveland declined to prosecute because investigators had failed to buy any weapons. Then he told Treasury officials that Leatherneck had to be shut down because Caliendo “had lost all control” of Downie and charged that the informant was “running amok,” according to documents obtained by the Times.

Plitman noted in his memo to Treasury investigators that he was involved in the operation “from the inception” and was “amazed” to learn that Caliendo had allegedly lost control of Downie.

“At no time during my involvement in this case did I ever hear one word about this kind of problem,” Plitman said in the memo. “And I had continuous contact with the Cleveland office throughout.”

Plitman acknowledged in his written statement that prosecutors “wanted guns on the table” before pursuing a prosecution. But he added that Customs ignored offers from Treasury officials “to do whatever was necessary to change that position to include the sending of a letter . . . explaining the critical and sensitive foreign policy and national security interests” at stake in pursuing the case.

According to Plitman’s memo, Siegel later offered a third explanation. The memo quotes Siegel as saying, “There were higher levels involved in the closing of this case.”

Plitman called Siegel’s assertion “a third reason [for closing the case] which no one had ever heard of before.”

Siegel never offered any further explanation on the identify of the high-level officials.

Caliendo, in his suit, is seeking to find out if there was pressure from high-level officials to remove him from the investigation and send him to Orange County.

Caliendo first joined the Customs service in 1983 after leaving the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms.

In 1984, Caliendo sued the BATF, charging retaliation for testimony on behalf of female agents in a sex discrimination suit against the agency. Caliendo charged that the agency refused to give him a service recognition award after he testified against the agency.

Caliendo settled for an undisclosed amount and the agency agreed to post a notice for 60 days at the entrance to its Cleveland office that the agency had violated Caliendo’s civil rights.

While working for the Customs Service, the weapons deal came up, and Caliendo, who in 1993 was awarded the Customs Commissioner’s Award for his participation in a drug case, began his investigation.

After Operation Leatherneck was terminated, Caliendo continued to work for Customs in Cleveland for three years, where he continued to ask questions about his removal from Operation Leatherneck.

In March, 1994, Caliendo was transferred to Los Angeles and then to Orange County despite the fact there were openings in the Cleveland office.

Adam F. Strzok, a Customs supervisory agent from Chicago assigned as an independent fact-finder in a grievance filed by Caliendo against the agency, quoted Plitman as saying that had Caliendo “been allowed to continue with the [Leatherneck] investigation, the case would have been made.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

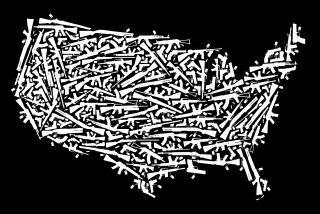

Shopping for Arms

Two U.S. arms merchants promised to deliver a variety of weapons ranging from aircraft to rifles. The weapons were to be sold to governments in Latin America or Africa. Here is a selection of the merchandise:

* UH-1 “Huey” helicopters

* C-130 Hercules aircraft

* M-16 rifles

* 155-millimeter howitzers

Also among the items on the list were:

* A-37 jet aircraft

* M-41 light tanks

* M-113 armored personnel carriers

* Mortars (81- and 106-millimeter)

* Recoilless rifles

* Surface-to-air launchers/missiles

* Machine guns (.30- and .50-caliber)

* F-5 jet aircraft

* M-1 Garand rifles

Source: Times reports

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.