BODY WATCH : An Eye on Safety : Goggles could prevent 90% of the 100,000 eye injuries that occur each year. But most kids worry more about how they look than about how they see.

- Share via

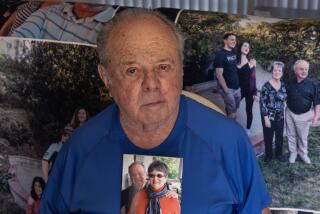

Stevie Korey celebrated his ninth birthday with family and 25 buddies at a restaurant equipped with a batting cage.

When Stevie’s turn at bat was over, the pitching machine threw an extra ball at his right eye.

Although he was wearing a helmet, his eye was unprotected.

Two days later he had eye surgery.

Today, two years later, his retina is held together artificially with a sclera buckle, he sees small balls of light and his peripheral vision is diminished. The Highland Park, Ill., boy is subject to vision problems for the rest of his life including glaucoma and cataracts.

These days, reports his mom, Shelley, “Stevie wears polycarbonate goggles for all sports activities now.” As does his brother, Jeff--the Korey boys are ambassadors of eye protection for Prevent Blindness America--and a lot of their friends.

They are the exception.

According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, more than 100,000 eye injuries occur annually during sports or recreational activities, and 90% of them could have been prevented. Yet, many athletes--amateur and professional alike--don’t wear eye protection.

“There’s not enough awareness out there,” Shelley Korey says.

As a result, eye doctors are touting sports goggles with lenses made of polycarbonate, a shatterproof plastic found in jet canopies and bullet-proof glass.

“Polycarbonate goggles are the recommended form of safety glass and do the best job in protecting eyes from sports injuries,” says Dr. Ronald E. Smith, professor of ophthalmology and chairman, Department of Ophthalmology at USC/Doheny Eye Institute and President of American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Injuries to unprotected eyes can range from a simple black eye to blindness.

Linda French, a member of the 1992 U.S. Olympics badminton team, recently learned about the advantages of goggles: safety and performance.

“A birdie can get up to 200 miles per hour so with goggles I’m not as nervous. They’re not attractive. I look like a bug. That’s why nobody considers wearing them but I think they’re really good.”

Says French’s eye doctor, Dr. Carl Hillier: “If you have goggles on, you know your eyes aren’t going to be injured so you don’t have to blink or lose eye contact with the ball.”

Hillier drives home the point to his young patients and their parents by letting the parents pound lenses with a sledgehammer.

“It won’t break. End of discussion.”

Persuading children to wear goggles, however, proves tougher, Hillier says. “It’s embarrassing for a little kid to put on safety goggles. Other kids make fun of them. Safety is almost secondary to interest kids in wearing goggles.”

Same goes for bigger kids.

Says Lakers trainer Gary Vitti: “We can encourage (players) to wear goggles, but you can’t make them wear them. The only guys who do wear them are the guys with eye injuries--they get a little gun-shy and wear them.

“A couple of years ago, (Laker) James Worthy, myself, and a sunglass manufacturer designed the goggle that is most predominantly worn in the NBA right now. They go around the cheekbone and are sanded on the bottom so it doesn’t rip the skin. As for fogging, we drilled holes in the plastic at the side of the nose and that worked.”

Some athletes resist eye protection even after they’ve been hurt.

Pauli Ramirez of San Diego broke his cheek and orbital bone on a fullback’s knee during a rugby match in 1993.

“When my eyeball finally fully opened, I didn’t like the looks of things. The eye wasn’t fully moving. Inside the whole eye was totally red. The vision was weird, blurred,” Ramirez says.

Even after two hours of surgery and his vision restored (though he still has some blurriness), he won’t wear goggles because, he says, he likes to keep his rugby uniform simple.

“You just wear jersey, shirts, socks and rugby boots and there’s no restrictions with helmets. A lot of times gear like that restricts you.” Besides, Ramirez adds, “I think plastic goggles would hurt someone during a tackle.”

Dr. John B. Jeffers, team ophthalmologist for the Philadelphia 76ers and the Eagles, says, “Part of the problem is, it is assumed to be not macho, ‘Not my style,’ even after they already get the eye injury.

“(Former Laker star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) wore goggles because he was hit in the eyes so much from fingers. He’d been scratched so many times that if he rubbed his eye the cement, the surface of the eye, could literally scrape off. (Abdul-Jabbar) did make it easier for me to recommend to at least kids to wear goggles and the old four-eyes (image) kind of got diluted.”

Abdul-Jabbar knows that most youngsters balk about wearing eye protection and he has some words of encouragement for kids.

“It certainly kept my career on line. If I hadn’t worn goggles, I would’ve retired early. My face was right in the area where people were swinging at the ball. First time in pro I was hurt so bad I lashed out in pain and broke my hand.

“I was the ‘lone ranger’ out there,” Abdul-Jabbar says. “I started wearing goggles 20 years ago and nobody was wearing them then. People would mention it but nobody ridiculed me. I remember a couple of times I could hear the click of somebody’s nails on my glasses and I knew I was doing the right thing. Tell kids don’t worry what other people think about that (goggles). Your eyes are crucial to your life. Kids have to protect their vision.”

Papa has spoken. There’ll be no more discussing it now, kids.

Hazards for Your Eyes

Here are the most common sports eye injuries:

* corneal abrasions (scratches)

* vitreous hemorrhage

* ocular lacerations

* black eye

* detached retina

* optic nerve damage

* blindness

* fracture of the bone around the eye

Source: Dr. Bruce M. Zagelbaum, eye-injury spokesman, American Academy of Ophthalmology

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.