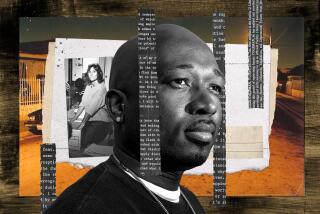

Ellie Nesler: Heroine or Hardened Vigilante? : Justice: Friends, neighbors and even total strangers have rallied around the woman who killed the alleged molester of her son. But others are troubled by what they see as runaway sympathy and blind support.

- Share via

What began in tragedy is sinking in sentiment.

Spaghetti suppers around Jamestown, Calif., are raising money for the defense of Ellie Nesler, the little mining town’s vigilante heroine. Total strangers send checks. Nesler’s sister has appeared before the California Legislature to testify on a bill increasing penalties for child molestation, specifically because of “the recent incident in Jamestown.”

But beyond the photo ops, the original dilemma remains: Does provocation justify a crime? It’s not hard to understand the rage that made Nesler draw a gun and shoot Daniel Driver, the man accused of molesting her son at a nearby church camp five years ago. Of course, you just can’t go around shooting people. But there’s great sympathy for the 40-year-old mother of two, for what is seen as both a mother’s anguish and a citizen’s despair over the failure of the legal system.

Driver had a record of molesting children, and while Nesler’s son, now 11, had suffered terribly, Driver seemed untouched. In fact, he seemed to smirk when the agitated boy vomited at a preliminary hearing April 2--at which point Ellie Nesler got her gun and shot him dead.

Already, the case--which is up for a preliminary hearing today--seems a bellwether for people fed up with today’s crime and today’s punishment. They looked at frontier justice, and they liked it.

Many, however, seem disturbed by what they see as runaway sympathy and unthinking support. As with any story of crime and passion, there are already changes in both stated facts and perceptions of the case and fears about the effects of the public sentiment.

“This is scary,” says Lauren Weis, Los Angeles deputy district attorney in charge of the sexual crimes and child abuse division. “Where does it stop? Can Driver’s mother now go in and get Nesler?”

*

On first impression, Ellie Nesler seems to fit the definition of a vigilante, though the word has different connotations to different people. Simply stated, vigilantism means “the law doesn’t do it for us,” says Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, “so we’ll take the law into our own hands.”

That said, vigilantes are still a mixed bag, ranging from the noble to the depraved. In Colonial America, says MIT history professor Pauline Maier, it could have been “a community asserting what was in the best interest of the community,” as when a whole group of colonists rose up to violate the British law that said they couldn’t cut down white pine trees.

It could also be a cross-section of the community going out one night to raze a barn whose owner refused to let a road go through. Though the purpose may seem less noble, “there was a consensus,” says Maier. “Their action was generally reasonable and limited, and it didn’t lead to anarchy.”

Things got a lot rougher on the 19th-Century frontier. Authorities were so few and far between that lone gunmen, posses and even mobs rushed to fill the gaps with what’s now called “frontier justice.” By the 20th Century, this frontier justice was not just beyond authority, it was often anti-authority, a thing of midnight mobs, white sheets and sawed-off shotguns.

Nesler has been compared to a more modern version--Bernhard Goetz, the New York “subway vigilante” who in 1984 shot four young thugs threatening him. But Goetz, unlike most vigilantes, was acting more in self-defense--or so he argued later--and he was reacting to a crime in progress, not demanding redress for a past crime.

*

“Vigilante” may not fit Ellie Nesler perfectly, either. The legal system was moving along and it hadn’t really failed her yet, though it was certainly neither swift nor severe with Daniel Driver.

Contrary to most reports, Driver had in fact done time on a previous conviction for child molestation. In October, 1983, he’d been convicted in Santa Clara County on two counts of felony child molestation--one charge of oral copulation involving a 10-year-old boy he’d been baby-sitting and one charge of fondling an 8-year-old at a day-care center where he worked.

He was given five months in county jail and three years’ probation. It was a relatively light sentence because it was his first sex offense and because a half-dozen parents wrote the court on his behalf. Furthermore, the doctor who evaluated him didn’t think he’d re-offend--an unlikely belief today, given our current understanding of pedophilia. Driver served three of the five months, with credit for good behavior.

What’s more, although it had taken some time to catch him, Driver was in custody in the Jamestown case. He’d allegedly sodomized Nesler’s son and molested several other boys while working at their church camp from mid-1986 to mid-1988 and was charged with the crimes in 1989. He wasn’t caught, however, until late 1992, when he was arrested for shoplifting in another county.

At the April hearing, Nesler and the other parents apparently believed their children’s testimony wasn’t making a strong impression and that Driver might “walk”--probably an erroneous impression. A preliminary hearing is generally pro forma: The decision to go to trial requires only a strong suspicion that something happened.

*

The popular slant on Nesler as a vigilante may also be too limited as a way of understanding her action.

“It doesn’t capture the context, which is that of a mother in terrible pain who wants to lash back,” says UCLA law professor Peter Arenella.

Seen in that light, Nesler’s impatience with the legal system is more understandable.

“The wheels of justice grind very slowly and don’t always turn out the way we want,” says Weis. “I understand the frustration--it seems like all the constitutional protections are for the suspect, not the victim--but I would just ask them to have patience and trust us.”

At the least, some suggest, Nesler might have trusted in a jury drawn from her own community.

“I heard that had (Driver) been convicted, he might have looked at a couple of decades in prison,” says Dorothy Ehrlich, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union for Northern California. “The spirit that feeds support of her would also feed a jury that feels as strongly.” (Charged with four counts of child molestation, without force, Driver could have gotten 14 years plus five more for each prior offense.)

*

Now that Nesler is on trial, she has to trust in the jury. “This is the kind of case,” says Weis, “where a jury might sidestep the law and consider issues such as personal interest, sympathy, pity.”

But it may be hard to predict. Now that Nesler’s the accused, her background becomes relevant. For all the frontier aspects of the region and the public support for her, some residents may be offended by her familiarity with guns. Some may be offended by her earlier conviction, more than two decades ago, for auto theft--for which she served two months with the California Youth Authority in 1971 and two years’ parole.

The consensus is that her best chance lies in pleading insanity, not the moral-justification argument suggested by the first lawyer she hired (then fired, then hired again, then fired again). She entered an insanity plea late last week.

“It would be hard to imagine a judge permitting the argument that it’s justifiable to take a life for an act that’s not even subject to the death penalty,” says Arenella.

Even when a community can sympathize, it “doesn’t make that action justifiable or appropriate,” he says. But “the point of the defense of insanity is that it allows one an excuse for wrongful acts--and allows the jury to convey sympathy and understanding for the pressures this person is under.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.