Big Gains Made in Treating Children’s Cancer

- Share via

Oncologists asked to name the greatest success in cancer research in the last 20 years invariably point to one area: children’s cancer.

Cure rates have soared for many childhood cancers. But the reasons for this success are only partially clear.

* Many of the so-called children’s cancers are types that are much more responsive to chemotherapy.

* Children appear to tolerate cancer treatment better, physically and emotionally.

* Pediatric oncologists have long advocated a team approach to treating cancer, drawing in many specialists and applying a combination of treatments at a few highly sophisticated hospitals. This approach also has more recently become popular in certain segments of adult oncology.

But pediatric oncologists owe a lot to luck, says Dr. Joseph V. Simone, director of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., a major child cancer research and treatment facility.

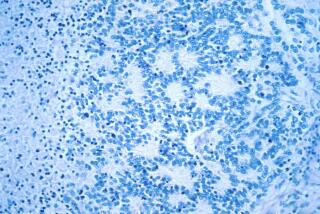

Many childhood cancers arise in areas called embryonal tissue, which resembles the primordial tissue found in a developing embryo. Conversely, about 90% of adult cancers are carcinomas: cancers that arise in mature tissues of the lung, ovary, breast and colon.

“It turns out that, as a general class, embryonally derived tumors are more sensitive to the therapeutic tools that we have than the carcinomas,” says Simone.

But childhood cancer is far from being conquered. Though cure rates are rising, so is the rate at which cancer strikes children, and doctors are not sure why, says Dr. Stuart Siegel, director of the division of hematology/oncology at Childrens Hospital of Los Angeles.

“We need to find out about why these cancers occur,” Siegel says. “While we know quite a bit about causes of adult cancers, we don’t know much about childhood cancer, which isn’t likely to be environmental and is likely to be more related to things that happen at the molecular level of the genes.”

Further, Siegel notes, some cancers, such as brain cancer, are still largely resistant to treatment.

Researchers are also becoming increasingly concerned about the long-term effects of cancer treatment. Some cancer treatments, such as those commonly used in Hodgkin’s disease, are known to increase the risk of a second, separate cancer later in life.

“Many children are being cured now of cancer,” Siegel says. “Now, we have the luxury of worrying about what happens to them 10 or 20 years later. They may live 50 years beyond their cancer. What happens long term is very important.”