FILM REVIEW : Hawks Makes ‘Scarface’ Work Like Gangbusters

- Share via

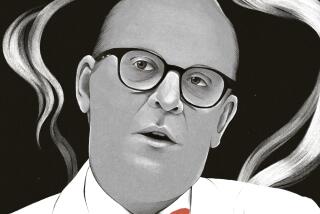

FULLERTON — Certainly, the weirdest figure to come out of the movies’ early-’30’s fascination with gangsters has to be Tony Camonte in Howard Hawks’ “Scarface: The Shame of the Nation.”

Played by a twitchy Paul Muni, he had both Edward G. Robinson’s Rico Bandello (“Little Caesar,” 1931) and James Cagney’s swaggering upstart in “Public Enemy” (also 1931) beat on the obsessive/compulsive scale. When not killing his enemies (and friends) with whistling nonchalance, he was eyeing his foxy sister with more than just brotherly love in mind.

It may be tough to fully figure the Robinson and Cagney characters--are they insane meanies with gun fixations or just ambitious entrepreneurs of the underworld set?--but there’s no doubt about Tony: He’s a loon, a pathological criminal who acts on every impulse.

“Scarface” (1932), which will be shown tonight at the Wilshire Auditorium as part of the North Orange County Community College District’s Great American Classics film series, was made in reaction to the budding career of Chicago mobster Al Capone; producer Howard Hughes was worried that authorities weren’t doing enough to control organized crime. Screenwriter Ben Hecht’s script loosely follows Capone’s own story in strikingly violent ways (there’s even an eerie, shadowy re-creation of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre).

The movie opens with a plea to the public to force local and federal officials to become more aggressive in battling the mob. A later scene (which seems thoroughly out of place--and in fact was tacked on to appease censors and other critics) finds a newspaper editor meeting with civic leaders to discuss the crime problem. The police take time from the action to warn against “glorifying and sentimentalizing” men like Tony.

Hawks proceeds to do just that. He was reacting to the moviegoers’ admiration for gangsters, the original anti-heroes who took things into their own hands and succeeded at it. That was pretty exciting for a country mired in the Great Depression. Tony’s rise through the mob ranks--he starts as a cold hit man and becomes the king of Chicago--has a can-do, almost jaunty air about it; he’s like an up-and-coming Wall Street arbitrager. Muni gives him a brio that--at first, anyway--masks the madness.

But later on, after Tony has revealed his desire for his sister (a lively Ann Dvorak) and killed his best friend (George Raft, doing his trademark coin-flipping for the first time), we realize just how spooky, and what a coward, Tony really is.

“Scarface” is one of best of the early gangster movies; its wit and building velocity speeds it past “Little Caesar” and keeps pace with “Public Enemy.” It may not improve on the latter’s best scenes--the ending, where Cagney’s heavily bandaged body comes crashing through the front door; the famous moment with Mae Clarke and a grapefruit--but “Scarface” has a consistently interesting visual style, not to mention its almost bizarre mix of brutality and preachiness.

The film is, by the way, surrounded by Hollywood lore. Legend has it that Hawks was so eager to have the gunfights appear real that he used live ammo in several key scenes; Harold Lloyd’s brother reportedly lost an eye from a stray bullet while visiting the set. Also, Hawks supposedly used Mafia hit men as “technical advisers” and even gabbed repeatedly with Capone about the making of the movie. Capone, the story goes, liked the finished product.

“Scarface: The Shame of the Nation” (1932) by Howard Hawks will be shown tonight at 7:30 at the Wilshire Auditorium, 330 N. Lemon St., Fullerton. Tickets: $4 and $5. Information: (714) 871-4030, Ext. 15.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.