COLUMN ONE : Childless Couples--New Hope : For those who have had multiple miscarriages, blood cells from the man are injected into the woman to prevent rejection of the fetus.

- Share via

Rhonda Gale took a red-eye flight from Los Angeles to Chicago one day in early 1989, arriving in Chicago just as the sun was rising. Carrying a cooler containing vials of her husband’s blood, Gale climbed into a limousine and was driven to the University of Chicago Medical School.

Medical staff there took the blood from Gale and, several hours later, injected a mixture containing Philip Klein’s white blood cells under the skin on Gale’s arm. She flew home the same day.

After several months and a second trip to Chicago, Gale and Klein were on their way to achieving a long-held dream: Gale soon became pregnant. And after three previous miscarriages, this pregnancy resulted in the birth of twin girls.

Gale and Klein are among a growing number of couples seeking a new and controversial treatment for repeated miscarriage. Called paternal leukocyte immunization, the treatment involves transferring immune-boosting white blood cells from the potential father to the potential mother before conception in order to improve the chances that the mother’s body won’t reject the fetus.

Candidates for the treatment are couples who have had three or more unexplained miscarriages early in the pregnancy.

While the treatment is still under investigation, it offers some hope in an area of obstetrics that has been one of the last to benefit from a wide range of new reproductive technologies.

Scientists have realized astounding success in the last decade in the treatment of infertility. Through advances in surgery, hormone therapy, in vitro fertilization, donation of eggs and sperm and surrogacy, the process of getting people pregnant now holds many options.

But staying pregnant can present another problem. When the cause of miscarriage is known, treatment is often available to improve the chance of a successful pregnancy. But for unexplained miscarriage, physicians traditionally could only tell couples to keep trying or consider artificial insemination with donor sperm.

“Recurrent pregnancy loss is something of an orphan among medical specialties,” says Dr. Pamela J. Boyer, who is studying the paternal leukocyte immunization at UCLA School of Medicine. “There aren’t a lot of options (for treatment), and there aren’t a lot of people interested in it. There hasn’t been a good place for patients to go.”

Beyond the issue of treatment, the emotional aftermath of miscarriage and its effect on couples who desperately want children has been ignored by the medical profession, says Susan Speraw, a registered nurse and doctoral candidate who is studying the subject for her thesis at the California School of Professional Psychology.

“There really is no literature on the psychological aspects of miscarriage. It’s like a nonentity,” she says. “I think the general concept is that because the pregnancy is lost so early it doesn’t have much meaning to the couple.”

Speraw’s ongoing study of couples who have experienced early miscarriages shows most feel a loss--”even if it’s just a loss of hopes and dreams.”

In recent years researchers have learned that miscarriage is exceedingly common. Most pregnancies spontaneously end within the first 28 days, before a woman usually knows she’s pregnant. Of pregnancies that are confirmed by a physician, another 15% to 25% end in miscarriage.

About half of those miscarriages are due to genetic defects of the fetus or structural problems that prevent the mother from carrying the fetus, such as a weakened uterus or cervix or hormonal problems.

Another large group of couples--several thousand, according to fertility experts--experience repeated miscarriages for unknown reasons.

Despite the important advance that paternal leukocyte immunization might represent, some fertility experts are concerned that couples are seeking the treatment before studies have shown that it actually works or why it works.

“It’s at a semi-experimental status,” says Dr. Susan Cowchock, a researcher at Jefferson Medical Center in Philadelphia who has been using the technique for about five years. “There is plenty of evidence that it’s helpful, but I don’t think anyone would feel it’s standardized treatment yet.”

Several thousand couples worldwide--many in England--have undergone the therapy. But only a few small, controlled studies have compared the success of couples treated with paternal leukocyte immunization to untreated couples, says Dr. D. Ware Branch, an assistant professor at the University of Utah.

At Utah, physicians are attempting to conduct a large, controlled, double-blind study but are having trouble attracting couples to the study because the couples fear they might be assigned to the untreated control group.

Yet Branch says the study is necessary because evidence is lacking that the treatment works.

“I think we don’t really know if it works,” he says. “Physicians over the years have felt confident about things that haven’t panned out. I think (the interest) is well- intentioned, but circumstantial evidence often doesn’t hold up to closer scrutiny.”

The treatment was first suggested in 1981 in research published by a British physician, W.P. Faulk, and Chicago physician Alan Beer, who treated Gale.

Both physicians were interested in studies that show immunological factors play an important role in establishing a successful pregnancy. And researchers say the studies related to paternal leukocyte immunization could illuminate basic mysteries of the immune system.

Normally, the human body rejects foreign material. Organ transplants, for example, are rejected unless the patient receives special, potent drugs to prevent the body from recognizing the organ as foreign tissue.

Since a fetus has half its genetic material from its father, a woman’s body--theoretically--should react to the fetus as foreign material.

Because that usually doesn’t happen, pregnancy has long been a source of wonderment to biologists. Years of studies have suggested that the mother’s body secretes protective antibodies in response to the fetus that keeps the fetus from being rejected by her immune system. Changes in the mother’s immune response during pregnancy have been detected, but experts disagree on which of these might be the protective factors.

“Somehow this baby that is half the father sits there and grows,” Boyer says. “I’ve always been fascinated by that process.”

Because of this paradox, some experts suggest that couples with repeated, unexplained miscarriages have similar immune system characteristics that somehow interfere with the normal protective mechanism. If the father and mother share similar immune system characteristics, “the baby, ironically, is not different enough so the mother doesn’t recognize it enough to lay down the protective layer,” says David Hill, laboratory director at the Center for Reproductive Medicine at Century City Hospital, whose program is an adjunct to Beer’s popular program in Chicago.

“This condition can be tested for by taking blood from the husband and the wife to see if this type of sharing phenomenon occurs,” Hill says.

Receiving an injection of the potential father’s blood--in effect, an immunization--causes numerous responses in the woman’s body, not all of which are understood, Boyer says. But when the “immunized” woman becomes pregnant, her body apparently recognizes the genetic material and responds appropriately to protect the baby.

“Her body has learned from the immunization to recognize her husband’s cells and respond appropriately,” Boyer says. “But no one seems to know how it actually works.”

Cowchock says the explanation is not that simple.

“(The treatment) may have nothing to do with interaction between the husband and wife,” she says. “No one knows why it might be helpful. It might be helpful in a mild way.”

While similar genetic material between the mother and father might be part of the problem, something else is probably going wrong in the mother’s ability to recognize the fetus, Boyer says.

“The going theory now seems to be that’s it’s a recognition problem,” she says. “(The fetus) has to be recognized and there has to be a response.”

Despite the mystery of how it works, Cowchock and other researchers say their studies show that couples who undergo the treatment have a 75% to 80% chance of carrying their next pregnancy to term.

But statistics show that women who have had three miscarriages have a 30% to 40% chance of carrying the next pregnancy to term without any treatment. So it’s impossible to know if the treatment helped couples or if they would have been successful anyway, Boyer says.

“Thirty to 40% are going to be successful anyway,” Boyer says.

But a growing number of patients are true believers.

Gale and Klein began trying to conceive in 1986. Because Gale had endometriosis, a condition of abnormal tissue growth outside the uterus, the couple underwent a procedure called gamete intra-Fallopian transfer, or GIFT, in late 1987. GIFT involves placing a mixture of eggs and sperm in the Fallopian tube.

Gale, an attorney, got pregnant three times with GIFT but miscarried all three times.

After the third miscarriage, Gale made an appointment with an adoption lawyer.

“I’d had enough,” she said. “I had been tested for everything. I knew something was the matter, but no one could figure out what it was.”

But while pursuing adoption, Gale and Klein heard about paternal leukocyte immunization. They shipped blood samples to Beer and were informed that the treatment might help them. Blood types do not matter except where the mother has an Rh negative blood type while the father is Rh positive, which could lead to complications.

Gale traveled to Chicago twice for transfusions. She became pregnant a few months later through a GIFT procedure. Early in the pregnancy, Gale received another boost of her husband’s blood. The twins, Allison and Juliana, were born Feb. 11.

Gale says some doctors familiar with the couple’s history have told her they doubt that the treatment was responsible for the successful pregnancy.

But, she says, “I really believe that without this treatment my kids would not be born. I don’t really think you can dispute it.”

Depending on the amount of laboratory tests needed, the treatment ranges from several hundred dollars to $2,000, experts and patients say.

Some insurers vary in their decision to cover the cost of the treatment. But those who call the American Fertility Society in Birmingham, Ala., an umbrella organization for fertility treatment centers, are told that the treatment is still under investigation, says spokeswoman Joyce Zeitz. “We have to tell them it’s purely experimental,” she says.

The completion of the double-blind study at Utah could help resolve many questions about the treatment. Utah officials are offering couples free treatment to enter the study. Couples who are assigned to the control group and don’t achieve a full-term pregnancy will be offered paternal leukocyte immunization later at no charge, Branch says.

Meanwhile, research on why the treatment works could yield significant information.

According to Hill, researchers are intrigued by the possibility that the treatment might improve the odds for couples who have no success at in vitro fertilization or GIFT.

An immune problem might also be a factor for couples with unexplained infertility--about 10% of all couples who cannot achieve pregnancy.

“We don’t know whether or not this thing can be extrapolated to the in vitro fertilization experience. But there is some evidence that this is so,” Hill says.

UCLA is also performing research on key immunological aspects of the treatment that might be beneficial in organ transplantation, Boyer says.

But even a modest reduction in miscarriage rates is significant, Boyer says. Women who miscarry often feel at fault because so little is known about the causes of miscarriage. In the past, some women have been told by doctors that they have a psychological aversion to pregnancy, she says.

“It used to be something people covered up,” she says. “The standard (treatment) was to tell people to try again. It has really been in the last five years that this has changed. This is a legitimate medical problem. This isn’t something you should suffer with and bury. You should get help.”

PATERNAL LEUKOCYTE IMMUNIZATION

Several thousand couples who desire to become parents experience repeated miscarriages for unknown reasons. Some medical experts now suspect that the woman’s body is failing to recognize the genetic material of the fetus and rejecting the fetus.

How paternal leukocyte immunization works:

1. The couple have blood tests to identify the similar characteristics of their immune systems.

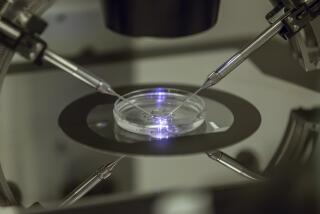

2. The husband’s blood sample is processed to remove the white blood cells, key immune-system cells.

3. The husband’s white blood cells are transfused to the wife, triggering her body to produce antibodies and other immune responses crucial to recognizing and protecting a fetus that is half the father’s genetic material.

4. After the woman conceives, signals are released from a layer of tissue surrounding the fetus--the trophoblast--alerting the woman’s body to produce protective cells and antibodies, protecting the fetus from rejection.

According to the theory, the woman’s body has learned from the transfusion to recognize her husband’s genetic material.

Blood sample

55% plasma

7% white blood cells

38% red blood cells