Clear Solutions for Poor Vision : Legally Blind Since Birth, He Founded Center to Help Partially Sighted People

- Share via

Samuel Genensky has been legally blind since birth, when someone in the hospital poured an alkaline solution into his eyes instead of the silver nitrate used to prevent infection. He has no sight in his left eye, and can only see light and dark shapes with his right.

Instead of letting his disability hinder him, Genensky, 62, has spent his life finding new ways to enhance his limited eyesight. And at the Center for the Partially Sighted, a nonprofit Santa Monica facility he founded, he shares his philosophy with hundreds of other people like himself.

By Genensky’s definition, a partially sighted person is someone who, even with the help of corrective lenses, can’t read the newspaper when held at arm’s length.

Last year, more than 1,200 people, many of them senior citizens, visited the Center at 720 Wilshire Blvd. Most of them were left partially blind as a result of diseases like macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy, both of which can hit suddenly or gradually.

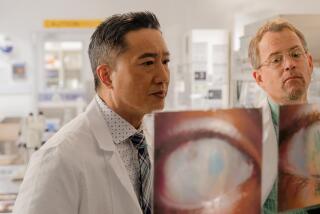

At the center, clients are examined by doctors and taught to use telescopic lenses and other vision aid devices. They are counseled by psychologists, taught independent living skills and take part in support groups.

In addition, the center provides a telephone network for patients, run by 60 volunteers, about half of whom are partially sighted.

“These people are rather isolated; one, because they are too frail to move about, or because they just don’t have the confidence. (The volunteers) call them up and bolster these folks,” he said.

The volunteers also try to find out what patients need that they may be too shy to articulate at the center.

Sometimes, the answer to someone’s vision problem may be amazingly simple, Genensky said: a pair of binoculars or even a magnifying glass.

“My philosophy is, if it works, use it!” Genensky said.

As a child in New Bedford, Mass., Genensky used eyeglasses and was put in special classes that his school district offered for children with poor vision. But his eyeglasses didn’t help much when he went to a ballgame.

“There was this green patch and this grayish blur in the middle. My dad would cheer, the whole crowd would cheer, and I thought that was baseball,” he said. He recalled the day he brought his father’s binoculars along for the first time.

“I remember it was the Detroit Tigers, because Rudy York was pitching. I could see the players. My father was so awed by the fact that the binoculars helped me. He hadn’t realized how much I couldn’t see. But neither had I.”

When it came time for high school, Genensky was sent to the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Mass.

He hated it. “They tried to convert me into being a totally blind person. When you’re 5 or 6, people can mold you into just about anything, but I was 13. When you’re 13, there’s a certain orneriness that comes into you.”

Genensky left after a year there and was admitted to New Bedford High School, where he excelled. He went on to earn his doctorate in math at Brown University, and moved to Pacific Palisades with his wife, Marion, to work for the RAND Corp. as a strategic analyst.

It was at RAND that Genensky again found a way to enhance his eyesight as a solution to spending long hours painfully bent over his reading: closed circuit television.

“One of my colleagues said there’s gotta be a better way than slumping over your drawing board,” he recalled.

In 1966, he and his colleagues designed Randsight, the first closed-circuit television for practical use as a reading aid. The promotion of the instrument, which enlarges written material and shows it on a television screen, was only the beginning of Genensky’s work for the partially sighted.

“It was then I first noticed that partially sighted people either got no help at all, or only got help for the blind. That’s how I first got the concept for the center.”

He opened a center for low-vision examinations and aids as a department of Santa Monica Hospital in 1978, and it incorporated in 1983 as the Center for the Partially Sighted.

Although he is “mainly a fund-raising machine” now, Genensky said he tries to share his philosophy of making the most of one’s eyesight with those who come to the center.

“I sit down and try to be a role model. I say, ‘You may be legally blind, but that doesn’t make you totally blind. Your life goes on.’ ”

“I have no objection to learning Braille. But if I can use my eyesight and can use closed-circuit TV, I’m going to do that.”

Some patients, especially teen-agers, balk at using the large telescopic lenses or other devices they may need, Genensky said.

“They say, ‘I don’t want to use that. It looks funny!’ I say, I’m going to give you my ‘it’s fun to be different lecture.’

“The first day, there will be stares, there will be remarks. Some people may even be hurtful. The second day, there may be a few remarks. But by the third day, no one will notice.

“People develop respect for you because you’re willing to do something to help yourself.”

Genensky has found himself applying his philosophy anew.

After his wife died last year, Genensky realized he didn’t know how to cook, so he took lessons from a woman who teaches independent living skills at the center.

“This totally blind lady got me to use this big cleaving knife. I thought, hey, if she can do it, I can do it.”

In November of 1988, the scar tissue in his right eye began to break up, and Genensky underwent surgery. Now he has double vision in the one eye that works. Recently, he began using a cane when walking outdoors, because he no longer felt completely sure of himself.

“There was a little trauma. But I’ve learned to live with it. You adapt.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.