N.Y.’s Angry Stepchild Acts Up : Cities: Many residents of Staten Island are fed up with garbage dumps and pollution and want to secede. But officials won’t let them go without a fight.

- Share via

NEW YORK — Many residents complain it is the Rodney Dangerfield of boroughs: It gets no respect. Even Staten Island’s attempt to withdraw from the rest of New York City has been labeled a sitcom secession.

For most people, Staten Island is the forgotten of the five boroughs forming New York City, the mere end of a spectacular ferry ride. Its 400,000 people--only 5% of the city’s total--reside on an island 2 1/2 times larger than Manhattan, containing broad stretches of woods and hills as steep as San Francisco’s.

But they also reside with the world’s largest garbage dump, situated euphemistically in an area known as Fresh Kills. And the litany of complaints Staten Islanders have with New York City, and their support of the island’s secession movement, seems to grow in direct proportion to proximity to the dump.

How big is it?

Proponents of secession have their comparisons handy. Like the Great Wall of China, the dump can be seen by the naked eye from outer space, they say, noting that the dump receives 97% of the rest of New York City’s garbage--up to 27,000 tons a day.

“You can imagine what that means,” said Daniel Singletary, a leading secession advocate and an island resident for a quarter of a century. “That equates to, at the end of the week, more garbage than the weight of every man, woman and child living on Staten Island.”

How bad is the dump?

“The quality of life has deteriorated for people on a major portion of the island,” Singletary said. “The stench from the garbage is so overwhelming even in the winter I find it hard to go out to shopping malls and streets. People have to cower inside their homes.”

Many other residents agree.

“It’s awful. It’s filthy. You get pollution from New Jersey and from the refineries,” said Robert Payenson, 58, as he rode the ferry from Manhattan back to his home on the island. “The smell (from the dump) is sometimes just overwhelming.”

On windy days, refuse from the dump blows for miles creating another phenomenon: trees covered with brightly-colored plastic bags.

“It looks like Christmas,” Singletary said.

When the wind blows wrong, smells from the dump mix with pungent odors from New Jersey’s chemical plants and refineries. On those days, many residents within wind’s range complain of allergies and eye irritation.

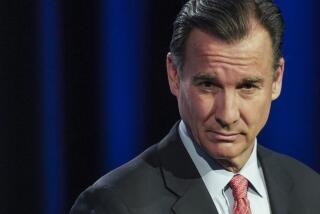

Guy V. Molinari, Staten Island’s borough president, routinely quizzes the two classes of schoolchildren who visit his office every week.

“I will ask the class how many of you have a serious sinus or allergy problem? Invariably, 50% of the class will raise their hands. My daughter has asthma. My father died of lung cancer. He didn’t smoke.”

The dump is a towering symbol of what many Staten Islanders believe: They are the stepchild of city government and are being dumped on by more than garbage.

Residents complain of both geographic and political isolation. The ferry costs only 25 cents, but it is not convenient for many Staten Islanders. By contrast, the round trip to Manhattan by express bus service costs $8 a day. The toll by car over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge to Brooklyn is $5, plus $2.50 each way through the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel to lower Manhattan.

On top of top this, many residents argue that Staten Island receives fewer municipal services than New York’s other boroughs. While the rest of the city has subways, only one rail line runs on the island. Disgruntled homeowners say sewers are inadequate and streets are flooded after heavy rains. They complain urban sprawl has threatened the island’s traditional small town atmosphere.

The Arthur Kill and the nearby Kill Van Kull--a 16-mile stretch of water separating Staten Island from northern New Jersey--has become as national symbol of pollution. In the most recent major spill, a barge carrying 4.2 million gallons of diesel fuel exploded in flames, spewing up to 200,000 gallons of heating oil into the water. Last year, more than 100 spills occurred on the waterway.

Against this backdrop of discontent, the U.S. Supreme Court ignited the kindling of secession. In a decision last year, the court ruled that New York City’s government was unconstitutional because it violated the one-man, one-vote rule. The result was a change in the city charter, abolishing the Board of Estimate, where each borough had one vote.

Previously, Staten Island had the same clout on the Board of Estimate as Manhattan. The board had been a crucial governmental body, dealing with the budget, land use, municipal contracts and other politically sensitive items.

Fearing its political power had all but evaporated, that it would only have 3 out of 51 votes in an enlarged City Council, Staten Island pressed for a municipal divorce.

A bill sponsored by state Sen. John J. Marchi--already passed by both houses of the Legislature and signed by Governor Mario M. Cuomo--has started a long process designed to lead to secession. Unless the law is found unconstitutional in the courts, Staten Island residents will vote in November whether they should leave New York City.

If the answer is affirmative, the process of drafting a new charter would begin. The proposed charter would be placed on the ballot within three years in a referendum in which only Staten Islanders could vote.

The Legislature then would vote a second time on secession. Many politicians believe this vote would be negative because far more legislators come from the rest of the city than from Staten Island.

Mindful of these hurdles and the fact the first bill only passed as a courtesy to two Staten Island members of the State Assembly, a New York Times headline characterized the movement as a “sitcom secession.”

Many politicians believe large numbers of Staten Island residents who may vote a first time for secession as a protest will eventually reject the second referendum once they realize its consequences.

While many Staten Islanders feel they are being shortchanged, New York City provides a broad array of municipal services including 55 schools, 11 libraries, 18 firehouses, three police stations, 33,475 street lights and 650 miles of sewers. All of these and other items would have to be financed if Staten Island became an independent city.

Secession advocates say preliminary studies show the island has the financial resources and tax base to be independent.

Lawyers for New York City have have gone to court to try to stop secession before the first vote. They argue that secession is illegal because it gives residents of the island the only voice in a matter affecting all of New York City.

The city’s lawyers say the state statute authorizing the test vote is illegal because it was enacted without a home-rule message from the mayor and the New York City Council, violating home-rule provisions of the state constitution as well as the 14th Amendment to U.S. Constitution.

“In the nearly 100 years since the consolidation of the city, important and strong bonds have been established among the five boroughs,” said Victor A. Kovner, New York City’s corporation counsel in his brief opposing secession.

“The secession of Staten Island would remove from the city more people than the entire population of Buffalo, and more people than the populations of Rochester and Albany combined or Syracuse and Albany combined.”

In an affidavit, Kovner argued that secession would remove substantial resources from the rest of the city, including 27% of its stock of single- and two-family homes. Secession also would have important implications for New York City’s debt.

“The city has issued more than $10 billion in outstanding long-term bonded debt,” the corporation counsel said. “Staten Island has received the benefit of this debt and has an obligation to bear a portion of it.”

Until Staten Island, the most serious threatened secession in New York state occurred in 1915 when residents tried to create Rockaway City out of part of New York City’s borough of Queens. That plan eventually failed in the state Legislature.

Giovanni da Verrazano first glimpsed Staten Island in 1524. The Dutch explorer Henry Hudson christened it Staaten Eylandt in 1609. But it really was discovered in 1964 when the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge linking the borough with Brooklyn was completed.

The ready access to the rest of the city brought a building boom that fundamentally changed parts of the once bucolic borough. Open land was replaced by rows of townhouses and single-family structures. Once countrified neighborhoods fell victim to urban sprawl, and to the huge dump.

“When I first moved, it had all the qualities of a suburban area as well as the convenience of living in the city,” said Edward Gonzales, a Wall Street broker, who has lived on the island for more than 15 years.

“Most people in other boroughs still think of Staten island as farmland. As a Staten Islander, I enjoy having open spaces, not living on top of each other . . . but I feel that is being threatened by growth,” said John J. Connolly IV, a resident for 21 years.

For all the complaints, pockets of Staten Island retain echoes of simpler times.

“There are some areas of Staten Island where you would swear you are in Upstate New York,” said Molinari. “Last night, when I got out of my car, I had to kick two raccoons out of my way to get into my house.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.